Drug Hopes to Delay Onset of Alzheimer’s Symptoms With a Monthly Shot in the Arm

An Alzheimer's drug is attracting the spotlight as it enters clinical trials. The drug, called solanezumab, appears to slow the buildup of amyloid beta in the brain and improves cognitive function in patients with mild dementia when given as a monthly shot. But the excitement about the drug is as much a measure of other treatments’ failures as it is of its success.

Share

Alzheimer’s disease is on the rise, even as doctors continue to struggle to find potential treatments for it. Researchers expect the number of those suffering from dementia to grow from 44 million at present to three times that by 2050.

The growing number puts increased pressure on researchers to do something to ameliorate the disease. And one drug is attracting the spotlight as it enters clinical trials. Eric Karran, the director of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, said in a press conference in the lead-up to a G8 summit on dementia that he is “full of hope” that a drug now being tested in the United States on patients with mild dementia may be to Alzheimer's disease what statins are to heart disease.

The drug, called solanezumab, appears to slow the buildup of amyloid beta in the brain and improves cognitive function in patients with mild dementia when given as a monthly shot.

But the excitement about the drug is as much a measure of other treatments’ failures as it is of its success. Researchers don’t even know for sure that amyloid beta causes Alzheimer’s-related dementia, although it is clearly linked. And solanezumab has already been shown not to help those whose dementia is more than mild.

In a clinical trial on patients with mild and moderate dementia, the results first showed no cognitive improvements. It was only after researchers re-crunched the data, which included standard mental tests used on patients with dementia, that they found improvements in patients with mild dementia hiding in the overall results.

Other drugs that have showed promise in the lab have sometimes affected amyloid beta levels but have not produced even these small cognitive improvements in Alzheimer’s patients.

"The marginal benefits of solanezumab are encouraging to support continued evaluation in future studies, and offer small support in favor of the ongoing viability of the 'amyloid cascade hypothesis,'" Harvard researchers tepidly concluded in a recent review of the literature on the drug.

The current trial, set to study more then 2,000 patients for three years, will include only patients with mild dementia. It hopes to show that over time, even modest improvements can mean several years with better quality of life.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Scientists believe that the physical changes wrought by Alzheimer’s disease begin as many as 10 years before symptoms appear.

If the trial lives up to researchers’ hopes, solanezumab would almost certainly be embraced by patients and their families. It would also make a bundle for its maker, Eli Lilly. The drug would function more or less like a preventative, meaning that those at elevated risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease would take it monthly for years.

"It is likely that, although statistically significant, the [improvement] will be of limited clinical relevance. It is likely that in a situation in which no new drugs have been approved for AD in several years, this limited benefit ... will translate into a significant commercial success," Bruno Imbimbo of Chiesi Farmaceutici told Singularity Hub.

There are more than 100 clinical trials under way for drugs that target Alzheimer’s disease. Just a few are testing drugs that would treat the disease directly, rather than treating its symptoms. With such a dearth of solutions, it's understandable that a modest record of success like Lilly's would generate enthusiasm.

But the real question is how much it will help patients, and we won't know that until 2016 when the clinical trial ends.

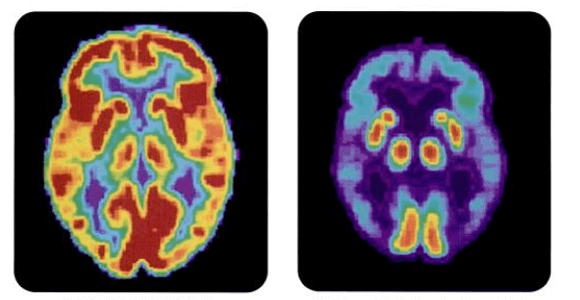

Images: PET scans of healthy patient and one with Alzheimer's disease, NIH via Wikimedia Commons; elderly men, Forster Forest via Shutterstock.com; amyloid beta diagram Boku wa Kage via Wikimedia Commons

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

What we’re reading