Expanded Google Fiber to Bring 10 Gigabit Internet in Coming Years

Google is on a mission to update the web's wiring—and they're not talking a decade or more to do it. The firm's CFO, Patrick Pichette, recently said his firm is working to boost internet speeds a thousand fold in the next three years. "That's where the world is going. It's going to happen." The project is called Google Fiber and, though it's in just three cities so far, an additional 34 cities in nine metro areas may be approved for Fiber by yearend.

Share

Google is on a mission to update the web's wiring—and they're not talking a decade or more to do it. Google CFO, Patrick Pichette, recently said his firm is working to boost internet speeds a thousand fold in the next three years.

"That's where the world is going. It's going to happen."

The project is called Google Fiber and, though it's in just three cities so far, an additional 34 cities in nine metro areas may be approved for Fiber by yearend.

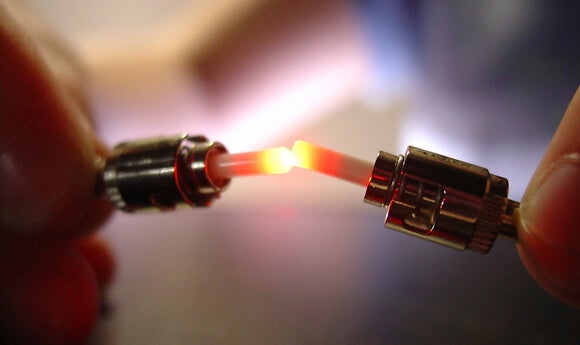

Most internet connections in the US travel copper wires, but as the name implies, Google Fiber achieves blistering speeds on fiber optic cable.

Information travels over fiber optics at about the speed of light with comparatively little degradation. Laser pulses send digital information along the cable, and by varying the frequency of the laser (i.e., its color), multiple signals can be sent simultaneously.

In the last year or so, Google’s been laying fiber in select US cities—Kansas City, Austin, and Provo, UT—choosing each based on ease of installation and local government cooperation. Current speeds are a hundred times the average connection on copper wires.

If you're lucky enough to be in one of the trial cities, you can buy Google Fiber's fastest connection for $70/month. For $120/month, you get that ultrafast connection plus cable television and a storage box to record shows. Or Google will provide a basic broadband connection—like the one you buy from your cable provider—for a one-time $300 installation fee. Monthly service is, thereafter, free for seven years.

Google Fiber is disruptive, and internet service is sorely in need of disruption. In many areas, cable providers control internet and cable television. They want folks to consume both products, and they'd prefer not to undertake costly, logistically challenging infrastructure updates.

But it's never been more tempting to cut the cord to cable and consume everything online.

Streaming media from the likes of Netflix, Amazon, or Hulu increasingly provide viewers high-quality, à la carte entertainment. Who wants to pay for hundreds of channels they don't watch to get the handful of channels they do—and all that on someone else's schedule?

To prevent streaming from cannibalizing cable, some think cable companies will ration information with data caps—adjusting caps and penalties to make it more palatable to stream some content and rely on traditional TV for the rest. Comcast already has a 300 GB/month data cap, though evidently they don't often enforce it.

While such strategies may provoke outrage, there's really nothing inherently wrong with them. They're business decisions—just shortsighted ones.

Scrambling to save traditional cable television is a losing battle. You can slow things down—expect a fierce, protracted battle in legislatures and court rooms—but you can't stop them from happening forever. The better, harder decision is to invest big in infrastructure now, so you can own the internet later. If you could only get a slice of one market, which would you choose?

Google's actions make their choice clear. The firm has never made any bones about getting as many people online consuming as many products as possible. Presumably, they'd rather not undertake giant infrastructure projects. But if it isn't happening, they'll make it happen.

While at first it didn't seem Google was going to broaden Google Fiber at a rapid pace, the recently expanded roster shows they're getting more serious.

Current Google Fiber cities in green, potential new cities in red. (Image courtesy of Google.)

Including expansion cities, you may notice the map is still pretty sparsely populated—this is an indication of just how involved infrastructure projects are. Even without entrenched interests, it will take years to build a nationwide fiber optic network.

Fibering a city requires political cooperation, careful planning, digging, and other traffic clogging activities. Projects in big, dense cities with big, dense lists of building rules and regs, like San Francisco or New York, are far more challenging than in smaller towns with fewer obstacles.

Indeed, while big cities carry on at suboptimal speeds, Chattanooga, Tennessee, a small town, with a population under 200,000 enjoys gigabit internet—alongside its push to upgrade the grid, the city's power utility, EPB, installed fiber optic cable.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Even for a small town, the project was no small task. Chattanooga spent some $300 million in total and had to lobby the state government to allow EPB to function as a telecom. EPB, meanwhile, had to confront Comcast and the state cable association in court.

Even as competitors like Google and EPB exert pressure on cable companies to update infrastructure and product offerings, it won't happen at light speed.

But it will happen. It has to. Demand for faster connection speeds is set to grow fast, and streaming entertainment is only the beginning.

Other applications include glitch-free, high-definition teleconferencing. In addition to Google Hangouts or FaceTime, this may include telepresence robots, both displaying the user by video and obeying their commands as well.

Imagine, for example, a doctor manipulating a Da Vinci surgical robot a thousand miles away—data speed and integrity would be crucial.

The quality of virtual worlds, like Second Life, varies directly with data speeds. Next generation worlds, like Philip Rosedale's High Fidelity, will be vastly richer at gigabit-plus speeds—not just for imagery and graphics, but to communicate head and body movements from sensored VR headsets, like Oculus Rift, gloves, body suits, or Kinect-like 3D mapping systems.

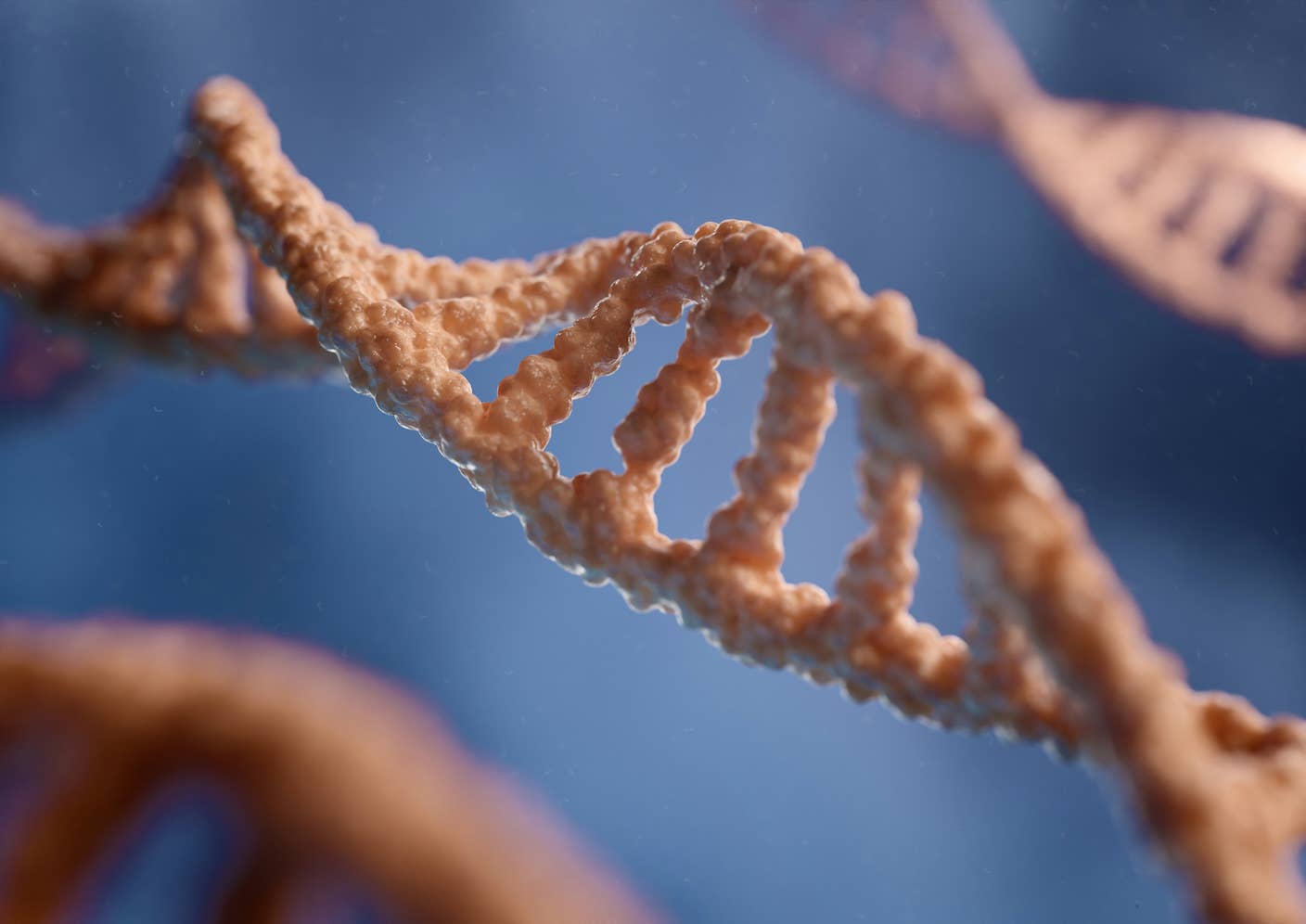

And if virtual worlds aren't your cup of tea, perfectly practical applications in health and medicine will increasingly involve data-heavy services.

Smartphone- or tablet-sized devices may soon act as intermediary between your body—vital signs, genetic tests, biological markers, imaging—and powerful cloud software capable of quickly analyzing the data and returning results not in a week or even a few days, but in hours or faster.

And how could we neglect to mention the Internet of Things?

Billions of devices will soon be chattering away to each other and their owners—optimizing and automating city infrastructure, office buildings, homes, and more. Some of this traffic will be handled by mobile providers, but a good fraction will also rely on WiFi connection to hard lines.

If information is the internet's lifeblood, the system is undergoing a nutrient-rich infusion. To make the most of new capabilities, we need to update the vasculature.

Image Credit: Barta IV/Flicker, Tim Pierce/Flickr, woodleywonderworks/Flickr, bat_ART/Flickr

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through January 31)

Is Time a Fundamental Part of Reality? A Quiet Revolution in Physics Suggests Not

Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo Decodes the Genome a Million ‘Letters’ at a Time

What we’re reading