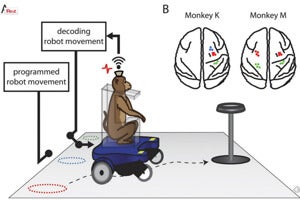

Watch Monkeys Drive Wheelchairs With Just Their Thoughts

Share

Duke University scientists have given a pair of monkeys the ability to drive a wheelchair with their thoughts alone. The work is described in a paper recently published in the journal Scientific Reports and adds to a growing body of work in brain-machine interfaces aiming to return some freedom to the severely disabled.

Duke neuroscientist Miguel Nicolelis and his team first began experimenting back in 2012, when they implanted hundreds of microfibers as thin as a human hair in the brains of two rhesus macaque monkeys. The fibers recorded cortical activity associated with "whole-body movement" and sent the signals to a computer.

To start, the monkeys sat in wheelchairs that were moved along various paths toward a bowl of grapes across the room. Their brain activity was read and decoded by a computer program and then associated with wheelchair commands.

Next, the monkeys were given control of the wheelchair. Over time they learned to steer it by thought alone—the implants sending their intentions to the computer, and the program recognizing and translating their thoughts into motion.

“Our data shows that the wheelchair is being assimilated by the monkey’s brain as an extension of its bodily representation of itself,” Nicolelis says. “In essence the wheelchair is becoming a part of the monkey’s body.”

This isn’t the first time brain implants have been used to control some external device. Nicolelis and his team have been working on brain-machine interfaces since 1999. Over the years, their monkeys have learned to control virtual arms, and their brains have even been linked together into a kind of organic, brain-network called a "brainet."

In other studies, monkeys controlled real robotic arms with their thoughts, and the BrainGate program has tested the technique in humans. Quadriplegic patients using BrainGate brain implants have learned to control robotic arms and perform simple but liberating tasks such as taking a sip of coffee from a bottle.

The Duke study, however, is notable for a few reasons.

Whereas prior experimentation in wheelchairs used joysticks in the training phase, this study shows joysticks aren't necessary—an important finding if similar techniques are to be useful for paralyzed patients who can't move their hands or arms.

Other attempts to control wheelchairs have used non-invasive, electrode-studded EEG caps to record brain activity. But EEG readings taken from outside lack the detail of an internal brain implant. Of course, the downside of such implants is invasive surgery.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Nicolelis and his team aimed to minimize these ill effects. Unlike other implants, which tend to be rigid, theirs are flexible, appear to cause less damage, and can better integrate into the brain. Further, they're wireless, while other implants are tethered.

Taken together, the implants pose less risk and can last longer—in this case, years instead of weeks or months—and Nicolelis says the monkeys remain quite healthy.

What's next? The research may move beyond wheelchairs.

“We are not focused on the wheelchair—we’re actually developing robotic exoskeletons in parallel to this,” Nicolelis says. “But in principle, it could be any kind of vehicle because this is a general purpose approach.”

Another goal is expanding the number of individual neurons (currently about 300) the implants can monitor. The team has reportedly shown the technique capable of monitoring up to 2,000 neurons. After that, they hope to move on to human trials.

Banner image courtesy of Shutterstock.com

Body images from "Wireless Cortical Brain-Machine Interface for Whole-Body Navigation in Primates," Scientific Reports. CC-BY

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

What we’re reading