New 3D Printed Ovaries Allow Infertile Mice to Give Birth

Share

It might be time to rethink fertility treatment.

Here’s the scoop: scientists at Northwestern University 3D printed a functional ovary out of Jello-like material and living cells. When implanted into mice that had their ovaries removed, the moms regained their monthly cycle and gave birth to healthy pups.

The scientists presented their results last week at the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston.

Although the study was done in mice, “we developed this implant with downstream human applications in mind,” says lead author Dr. Monica Laronda in a press release.

If successful in humans, the prosthetic would be able to extend the female reproductive lifespan by decades. What’s more, it may also help restore fertility and hormone function in women who can’t have kids due to ovarian issues.

The Problem

According to the CDC, 1.5 million women in the US are infertile. The causes are many, but roughly a quarter of all cases are due to irregular or abnormal function of the ovaries.

The ovaries are central organs for female reproduction because they release eggs that, once fertilized, develop into embryos. The ovaries also act like conductors, releasing hormones that orchestrate the entire reproductive system to function as one dynamic unit to sustain fertility.

It’s a highly complex and fragile system that sometimes goes awry.

Age is a big factor. Although increasingly couples are waiting longer to have kids, it becomes much harder for women to get pregnant past the age of 35. Most scientists currently believe that women are born with all the eggs that they will ever produce (although recent research suggests otherwise).

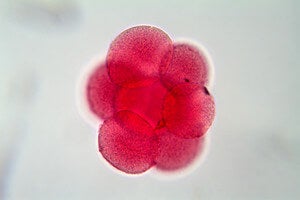

Egg cell under the microscope. Image credit: Shutterstock.com

With age, the quality of the eggs declines and may result in higher chances of acquiring random genetic mutations. The ovary milieu — a niche of hormone-releasing cells and other structures that help nurture the eggs — also begins to decay, making it harder for ovaries to release eggs on schedule.

Childhood cancer is another big factor.

Chemotherapy drugs often damage a dividing cell’s DNA, which kills off cancer cells but also harms egg cells and increases the chance of infertility.

“One of the biggest concerns for patients diagnosed with cancer is how the treatment may affect their fertility and hormone health,” says Laronda.

We hope that the prosthetic implant helps to restore their quality of life, she says.

The Implant

In order for the implant to properly work, it needs three things: immature egg cells (called “oocytes”), hormone-releasing cells that support oocytes, and a flexible but rigid enough scaffold that can support the growth of both cell types.

To generate the scaffold, scientists turned to gelatin, a glutinous biomaterial derived from the skin of animals. (It’s also the main ingredient of Jell-O.) Rather than recreating the entire complex structure of an ovary, the team took a minimalistic approach: using 3D printing, they generated scaffolds of different sizes and shapes to see which configuration works best.

Using immortalized human cells, Laronda and team found that the best structure had crisscrossing struts. The design probably worked best because it has multiple anchor points for cells to latch onto and also has a sufficient amount of space for oocytes to grow, explained the team.

Finally, mouse ovarian follicles — ball shaped units that contain both the oocyte and supporting cells — were seeded onto the scaffold to complete the prosthesis, which was then implanted into female mice that had their ovaries surgically removed.

The first promising sign came when the mice restored their hormonal cycle, suggesting that at least the hormone-producing cells were alive and functional.

Just this one result would’ve been awesome. Many women have decreased production of reproductive hormones due to diseases such as PCOS (Polycystic Ovary Syndrome) that can cause problems with bone density, weight and cardiovascular health, explained the researchers.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

A similar prosthesis may be able to combat those issues in at risk women.

But then came the bombshell: following the implant, the mice ovulated, gave birth to healthy pups and were able to nurse them until weaning.

When researchers examined the implant, they found that blood vessels had innervated the entire structure, thus providing nutrients and washing away waste and allowed the oocytes to develop normally into viable pups.

The fact that blood vessels automatically formed a network around the implant is huge. Often we need to add substances to stimulate the process, says Laronda, which could cause side effects and other complications. This 3D printing manufacturing technique bypasses that requirement and could influence future work on complex soft tissue replacement, she says.

The Future

It’s an impressive study, but for the implant to work in humans, the technique needs another element: stem cell technology.

Remember, a woman’s oocytes and supporting cells are a central component of the implant, but they’re often damaged due to age or disease treatments. Laronda and team believe that human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology can overcome this barrier.

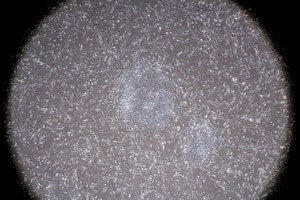

Induced pluripotent stem cells. Image credit: Shutterstock.com

The ability to recreate the oocytes and supporting cells has progressed rapidly in recent years, writes Laronda and colleagues in an earlier review paper. Human iPSCs derived from skin cells can be turned into primordial oocytes and supporting cells that display the same molecular signs of their natural counterparts, although whether they can fully develop remains to be tested.

Going from skin cell to stem cell to reproductive cells may seem like a difficult process, but much of this transformation process relies on physical forces, including the rigidity and structure of the ovary, wrote the authors. And that’s something that scientists can easily control with 3D printing.

iPSCs may not be the only solution either. A recent, potentially paradigm-shifting study suggests that women may have egg-making stem cells hidden away in their ovaries well into their 40s.

If — and that’s a big “if” — these cells could be coaxed in a dish to make egg cells, it would mean an unlimited supply of healthy egg cells that could be used to innervate the prosthetic ovary.

Whatever the case, in vitro fertilization (IVF) — now a decades old technology — may soon be getting a 21st century upgrade.

Image credit: Shutterstock.com

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

What we’re reading