MIT and Harvard Monitoring Cancer Tumors With an Implant

Share

Worried about the government spying on you through implants? Well, I don't know if your dental fillings are secret radios, but MIT and Harvard are definitely trying to keep tabs on your cancer. Their joint Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence (CCNE) has developed and tested a small cylindrical implant that monitors the growth of tumors. Dr. Michael J. Cima and his team believe the implant can help doctors monitor hormones, chemotherapy agents, acidity, and oxygen levels that are key indicators of cancerous growths. No longer will surgeons have to wonder if their excisions are successful.

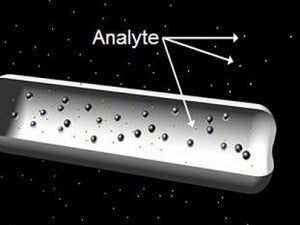

The little implant works in a really cool way. Only five millimeters long, the cylinder contains magnetic nanoparticles coated with antibodies. These antibodies will bond to whichever chemical the implant is designed to monitor. A semi-permeable membrane keeps the nanoparticles in the implant while still allowing ambient particles in and out. When the antibodies bond to a chemical they form clumps. These clumps are then read using an MRI.

It's surprising what you can learn from clumps. Chorionic gonadotropin is a hormone produced by human tumors. The CCNE implant Dr. Cima designed can help monitor levels of this hormone to determine the relative size of a tumor over time. Already, Cima's team has tested the effectiveness of their implant by using them on mice that have human tumors transplanted inside. Over the period of a month Cima was able to track the changes in tumors using their setup.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Giving mice human tumors sounds a little too much like mad-science, but the technology speaks for itself. While some researchers are developing take home kits to test for cancer, and others seek for robots to explore the body or have nanobots fight the disease, a passive and continuous monitor is a unique and necessary addition. The ability to correlate chemotherapy drug levels with tumor size is going to be crucial in customizing care to each patient. The implant, which could help determine if a tumor has metastasized, can be placed during the first biopsy, removing the need for repetitive exploratory surgery.

As mentioned by Catherine Mohr in her talks on advances in surgery, improvements in sensing are going to be as important as improvements in cutting. Surgeons need a better understanding of how their operations have affected their patient. The implant can serve that purpose while still helping other doctors choose chemotherapy levels or monitor how their patient is responding to another treatment.

Dr. Cima believes that a version of the implant that tests for pH levels could be ready in as few as five years. That's still a ways off, but it won't take long after the pH implants are approved before the hormone and oxygen level monitors follow suit. Continuous observations will be a successful ingredient in maintaining our health. Just like big brother always said.

Related Articles

AI Companies Are Betting Billions on AI Scaling Laws. Will Their Wager Pay Off?

Super Precise 3D Printer Uses a Mosquito’s Needle-Like Mouth as a Nozzle

Is the AI Bubble About to Burst? What to Watch for as the Markets Wobble

What we’re reading