Artificial Blood: Coming Soon to An Artery Near You

Share

Ask any vampire and she'll tell you, when it comes to blood there's nothing like the real thing. But as everyone who donates knows, hospitals and blood banks always seem to have dangerously low supplies. So scientists have gotten around to finding ways to make new blood, or something like blood, that doesn't have to come from humans but that can still supply human demand. The new blood comes in two flavors: blood substitutes (without red blood cells) and synthetically produced blood (derived from stem cells). While it looked like blood substitutes could be the dominant force in the market, that is quickly changing. Why? Well, it turns out that synthetic blood is less likely to kill you.

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and led by Dr. Charles Natanson has revealed that five major brands of blood substitute were increasing the likelihood of heart attacks and death. This has devastated interest in blood substitutes and bankrupted several companies that hoped to produce it. Synthetic blood is now the future vampire's soup du jour.

No matter which substance ultimately triumphs (and both may still succeed), natural blood donations may eventually become things of the past. Why worry about diseases, spoiling, and matching blood types when an endless supply of near perfect blood could be available. Hemophiliacs to wounded soldiers, everyone could end up enjoying a new kind of blood.

Fake Blood, Real Problems

Your blood's major duty is to carry nutrients, including oxygen. Hemoglobin, the chemical that absorbs and transfers O2 can be removed from your red blood cells. Outside of red blood cells, and mixed with oxygen rich materials and proprietary chemicals, hemoglobin has a long shelf life (12 months compared to normal blood's 6 weeks) can get oxygen to your cells fast, has little chance of transmitting disease, and avoids any need to match blood types. This miraculous fluid is known as a hemoglobin based blood substitute (HBBS). Back in the early 80s when 1 in 100 blood donations might contain a contaminant, HBBS seemed like a great idea. In the last five to ten years, that great idea started to seem like a real possibility.

Unfortunately, hemoglobin outside of red blood cells has a problem. It likes to scavenge nitric oxide (NO) and that's a bad thing. It can constrict your blood vessels, cause low blood flow, damage your pancreas, and cause heart attacks and death. Charles Natanson at the National Institute for Health and his teammates studied every bit of scientific literature they could get their hands on published between 1980 and 2008. Looking at just the cases where adults were given HBBS they found 16 clinical trials that used 5 brands of HBBS and discussed 3711 patients. As Natanson published in JAMA, HBBS led to a significant statistical increase in the risk of heart attack and death. These results were not limited to a particular brand or clinical trial.

Yeah, sometimes an entire class of kids flunks out. It happens. The five brands in question were: hemolink (created by Hemosol Bio Pharma), hemopure (created by Biopure Corp.), hemospan (Sangart, Inc), Optro (Baxter Worldwide), and Polyheme (Northfield Labs). Of those five, Northfield Labs and Biopure Corp both filed for bankruptcy, and Hemosol's website is suspiciously down most of the time.

Of course, every class has a teacher's pet. HemoBioTech, who wasn't included in the JAMA study, has supposedly lowered the toxicity of its brand of HBBS. Making molecules larger and more stable apparently alleviates some of the NO scavenging problems. The future of blood substitutes rest on the shoulders of HemoBioTech and other companies looking to create the next (and better generation) of HBBS.

I could do an entire story just on the aftermath of the Natanson JAMA article. Man, stuff hit the fan. Just some highlights: the FDA was very unwilling to release confidential/secret documents from HBBS manufacturers when Natanson was doing his research. This lead to some huge debates about whether the FDA should protect the privacy of companies when the public health is on the line. The FDA finally approached all five HBBS manufacturers and told them to go back to the drawing board. As we said, some companies folded under the pressure. The debate on what information should be available to peer scientists and reviewers is still raging on.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Need blood? Ask the frozen embryo for some help. Or maybe your baby's umbilical cord.

I wouldn't call it a fad, but it seems like every major medical problem these days is about to be cured by stem cells. In the case of blood, major research is underway in the UK and US to utilize stem cells to generate blood without a donor. That is, stem cells can be used to generate synthetic blood in a lab that is, for all intents and purposes, identical to normal blood from a human.

The Wellcome Trust, along with the blood transfusion services of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland are donating millions of pounds and expertise to research how embryonic stem cells can be converted into an endless blood supply. As ESCs can be coaxed to replicate almost infinitely, and stimulated to become red blood cells, an entire nation's blood supply might be able to be derived from just one discarded frozen in vitro fertilized embryo. An US company, Advanced Cell Technology is working on a similar project in the US, though it struggles with some of the legacy from the Bush administration's ban on ESC research.

Obviously ESCs bring with them ethical debates and considerations. Even if a single embryo could supply the nation's blood, that's a risky approach (never put all your red blood cells in one blood basket). Undoubtedly the use of ESCs to make synthetic blood will require the destruction of dozens of frozen embryos. For some, one would be too many. I'm sure the UK and US projects will face heated debate. Nothing really new about that, though.

Arteriocyte, Inc might sidestep the issue by creating synthetic blood not from ESCs, but from the blood taken from newly cut umbilical cords. Cord blood is an interesting topic unto itself and we'll be having a post on that real soon. Other types of adult stem cells, such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can also be converted. When it comes to new blood, umbilical cord stem cells and iPSCs don't have the oomph of ESCs, but they might still get the job done.

With the health risk problems facing HBBS, synthetic blood seems like the clear winner in the race to be the new blood. However, we should keep in mind that while 1 in 100 blood donations had problems in the 80s, the new statistic is much closer to 1 in 10 million. Huge improvements in screening tests have made donated blood extremely safe. So the only real advantage new blood has over traditional blood donations is availability, compatibility, and scalability. ESC derived blood will certainly be O-type and compatible, but it hasn't been shown to be scalable to large quantities. HBBS has its own scaling issues, but it is universally compatible, and can be stored for a long time.

Several years down the line, we may also want our new blood to be better than the old stuff. While in your body, the new blood could supply more oxygen stored in each red blood cell (or with each hemoglobin), have better transfer rates, and maybe provide increased resistance to infections. The ultimate goal would be respirocytes, a version of blood with nanotech containers holding stored oxygen so that you would have enhanced endurance. That's years or decades away from happening, but the new blood we discuss today might be precursors to that technology.

In the end, the competition between HBBS and stem cell generated blood is actually far from finished. Which is good news for all us blood-thirsty people out there. I always like it when technologies compete, it gives us better results faster. In the meantime I'm looking up how I can donate blood. It's old school, but it still saves lives. And it makes vampires happy. Double win.

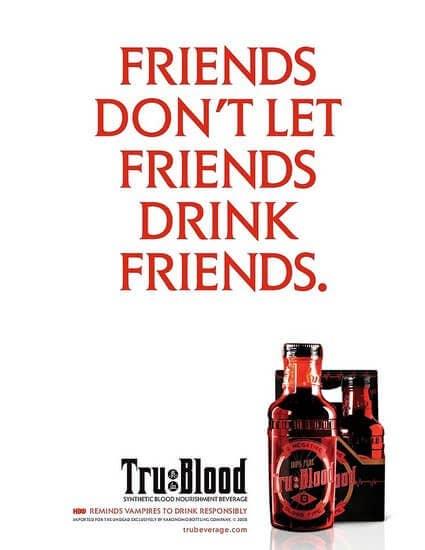

[photo credits: Showtime Ent.]

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 21)

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

This ‘Machine Eye’ Could Give Robots Superhuman Reflexes

What we’re reading