Genetically Engineered ‘EnviroPig’ Waiting For US Approval

Share

In the race to genetically engineer food that is tastier and cheaper, Canada's University of Guelph is instead finding a way to produce meat that may be more environmentally friendly. For more than a decade the UoG has been developing the 'enviropig', a genetically modified line of pigs that are better able to digest and process phosphorus. They are cheaper to feed because they do not require separate phosphorus food supplements, and they are better for the environment because they release up to 70% less phosphorus in their waste. Now in their eighth generation of enviropigs, the University of Guelph is still pursuing US FDA approval, and recently applied for the same from the Canadian Regulatory Agency. If successful, enviropigs could be the first transgenic meat to make a big impact on both pollution and your plate. Should the other billion or so pigs on the planet be nervous?

Genetically modified food is already on your table. Corn, soy, and rice (the big staple foods) have been GM for a while now, especially in the US, and the practice is growing all over the world. Generally the aim is to modify food so that it is pest and herbicide resistant, as well as bigger, juicer, tastier, etc - and there have been some promising results. Most countries have stalled in accepting genetically engineered meat, however. GE animals seem like a larger risk than plants. It's unclear if or when the public will warm up to the idea of modified meat, but genetic engineering has far more applications than just dinner. GM animals are likely to provide insights into how we may engineer ourselves for longevity, health, and intelligence - though probably not for taste.

For now, the enviropig has some promising advantages to offer, and they all center on phosphorus. Phosphorus is an important element, it's the 'P' in the famous NPK fertilizer approach to increasing crop yields. But that agricultural benefit can also be a curse. When pigs on modern farms defecate and urinate, they release a lot of phosphorus in the environment. With our centralized industrial agricultural system, this means that there is occasionally huge amounts of phosphorus dumped into a small area. When this element is washed into rivers and other bodies of water it can lead to steep increases in algae. Algae blooms disrupt natural oxygen levels and kill fish. In short, pig waste can be an environmental hazard. Enviropigs release up to 70% less phosphorus in their urine and feces. That means a smaller impact and a better chance of keeping balance in the ecosystems surrounding pig facilities.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

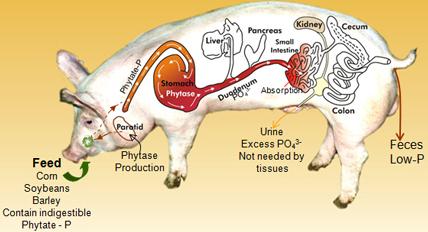

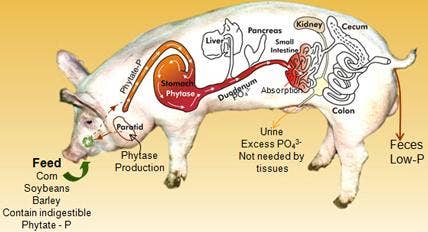

Enviropigs also eat better than their non-genetically modified brethren. DNA from mice and Escherichia coli bacteria have been spliced into their genome giving them saliva that helps to digest the phosphorus in grain. Most phosphorus (50-75%) in standard grain feed is indigestible to traditional pigs. Farmers have to give pigs supplements, or feed them phosphorus digesting enzymes (phytase) to keep them healthy. With the mouse and bacteria genes, enviropigs can eat a steady diet of feed grain without supplements, making them cheaper (and easier) to raise.

Why not just feed pigs something other than these grains? Well, those grains are cheap (sometimes because they are subsidized) and can be acquired in the huge amounts necessary to raise the millions of pigs we eat every year. Organic farmers (and other food advocates) point to the subsequent need for genetic modifications as a sign that the entire industrial-agricultural system needs rethinking.

Another concern about GM animals is the narrowing of the gene pool. Already the pigs we eat come from a very restricted number of bulls - yielding piglets that gain weight faster and produce juicer cuts of meats. This narrow gene pool, however, has also made the pigs more vulnerable to infection (amplified by the factory-style conditions of the modern farm). It's important to note that the FDA and CRA applications for the enviropig involve just one lineage of stock (the Cassie line, descended from one of the originally modified pigs). Proper breeding practices would keep the introduction of the enviropig from developing into a monoculture, but GM animals are undoubtedly going to narrow gene pool even further.

Whenever politics and economics come into play it's hard to predict how science will develop. Certainly there are some amazing benefits to be had by exploring genetic modification in animals. Those benefits probably need to be considered in the larger context of our modern industrial agricultural system. There's no reason why we can't pursue the best of all worlds: organic distributed farming ("traditional" agricultural) coupled with a polyculture approach to genetic engineering. No matter what the current politics and economics trends may be, there's little doubt that genetics will have an increasing role in agriculture in some fashion. Dairy cows are being genetically tested for breeding, flowers are being engineered to have different smells - the genie's already out of the bottle. It may be that GE foods, including pigs, will continue to form an increasing portion of our diets. Or we could jump ahead and just start eating artificial meat. Either way we're soon to find out just how tasty science can be.

[image credits: University of Guelph]

[source: University of Guelph, Golovan et al, 2001]

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 21)

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

This ‘Machine Eye’ Could Give Robots Superhuman Reflexes

What we’re reading