A Robot in Every Korean Kindergarten by 2013?

Share

If you want humans to fear and respect their robot overlords you have to start early. Elementary school children in Korea in the cities of Masan and Daegu are among the first to be exposed to robotic teachers. Among them is a robotic English instructor named EngKey developed by the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST). EngKey can hold scripted conversations with students to help them improve their language skills, or a modified version can act as a telepresence tool to allow distant teachers to interact with children. The arrival of EngKey to Masan and Daegu is just a small step in the mechanization of Korean classrooms: the Education Ministry wants all 8400 kindergartens in the nation to have robotic instructors by the end of 2013. Watch out kids, you don't want to misbehave when your teacher can crush you in its metallic grip.

As we reported earlier in the year, Korea has been looking to expand the role of robotic assistants in classrooms. Most models, including EngKey, act primarily in support roles for real human teachers. Rightfully so. EngKey can't handle improvisation, and students must follow a script carefully when practicing their pronunciation with the robot. The value of the bot comes in the student's fascination and comfort with a toy-like device. Students aren't intimidated as they may be with an adult, can more freely make mistakes, and hopefully, learn from them. Preschoolers seem to respond well to another robot used in classrooms, Genibo the dog. Teachers can use Genibo to show children dance and gymnastic moves, and their interest in the device helps maintain their attention through the lesson.

Of course, the novelty of robots can wear off with continued exposure, and I'm not sure about the longterm use of robots as attention-getting assistants. In second grade I really loved learning using audio books on a cassette, but I quickly figured out it was the same lectures as I normally got in the classroom, just captured on tape. Korea's probably right to focus the first wave of their robotics programs at the youngest children. CNN reports that the Education Ministry is hoping to have 830 bots in preschools by year's end. At that age, a robot may stay interesting for a longer time. Eventually, however, robots that can't act like humans are going to have a hard time of instructing human children.

Have no fear, though, Korea seems to have thought of that possibility. Robots like EngKey can also serve as valuable portals for telepresence. In that capacity it allows Korea to hire English speakers around the world to teach in their classrooms at a fraction of the price of traditional instructors who are shipped into the country. Currently, Korea is one of the largest importers of semi-professional English instructors (I have a friend there now), so switching to a telerobotics solution could save them considerable money. Once telerobots are brought in for English, they could stay to help with other subjects.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

So, EngKey and other robots could serve as a first wave of mediocre robotic teachers, probably followed (or run in parallel) with telepresence enabled instructors...and then what? Well, maybe we'll have robotics teachers that can actually replace, not just assist, humans. Though I'm a little disinclined to believe him, Choi Mun-taek (a team leader at KIST) told the NY Times that “in three to five years, Engkey will mature enough to replace native speakers.” That's a very fast time table, and it's not clear if 'replacing native speakers' means going off script, or just being able to fine tune accents perfectly. Either way, 2015 seems a little early to have robots out English-ing the English.

Some day, however, we will develop robots that can handle simple lessons as well as many human teachers, but with infinite patience and an encyclopedic knowledge of any subject. That will present school districts with a distinct incentive to include them in many, if not all, classrooms. Assuming, of course, that we continue to even have traditional classes in the years ahead. As I've mentioned before, digital education could drastically reshape the way we approach teaching students. Textbooks may be discarded and lessons customized to each individual student. It's unclear what role teachers (robotic or otherwise) would play in an educational setting dominated by the internet, hypertext, and instructional videos.

Maybe, however, Korea's focus on robots in the classroom is less about education and more about robotics. This is the same nation, I may remind you, that has a robot theme park in the works. The real benefit could be in a generation that is comfortable, familiar, and engaged with robot technology. Look at our current hardware and software gurus and I'll bet you find a lot of adults that took apart and played with machines as children. By making robots accessible to students at a very early age, Korea could be building a similar wave of young enthusiasts that could float the nation to the top of the global robotic economy of the future. Or maybe the Education Ministry really does think that robot dogs will help teach kids gymnastics. Either way, the age of android teachers is dawning in Korea and it could spread to your neck of the globe soon. Tell your kids to start bringing batteries to class - it never hurts to get on a teacher's good side.

Related Articles

These Robots Are the Size of Single Cells and Cost Just a Penny Apiece

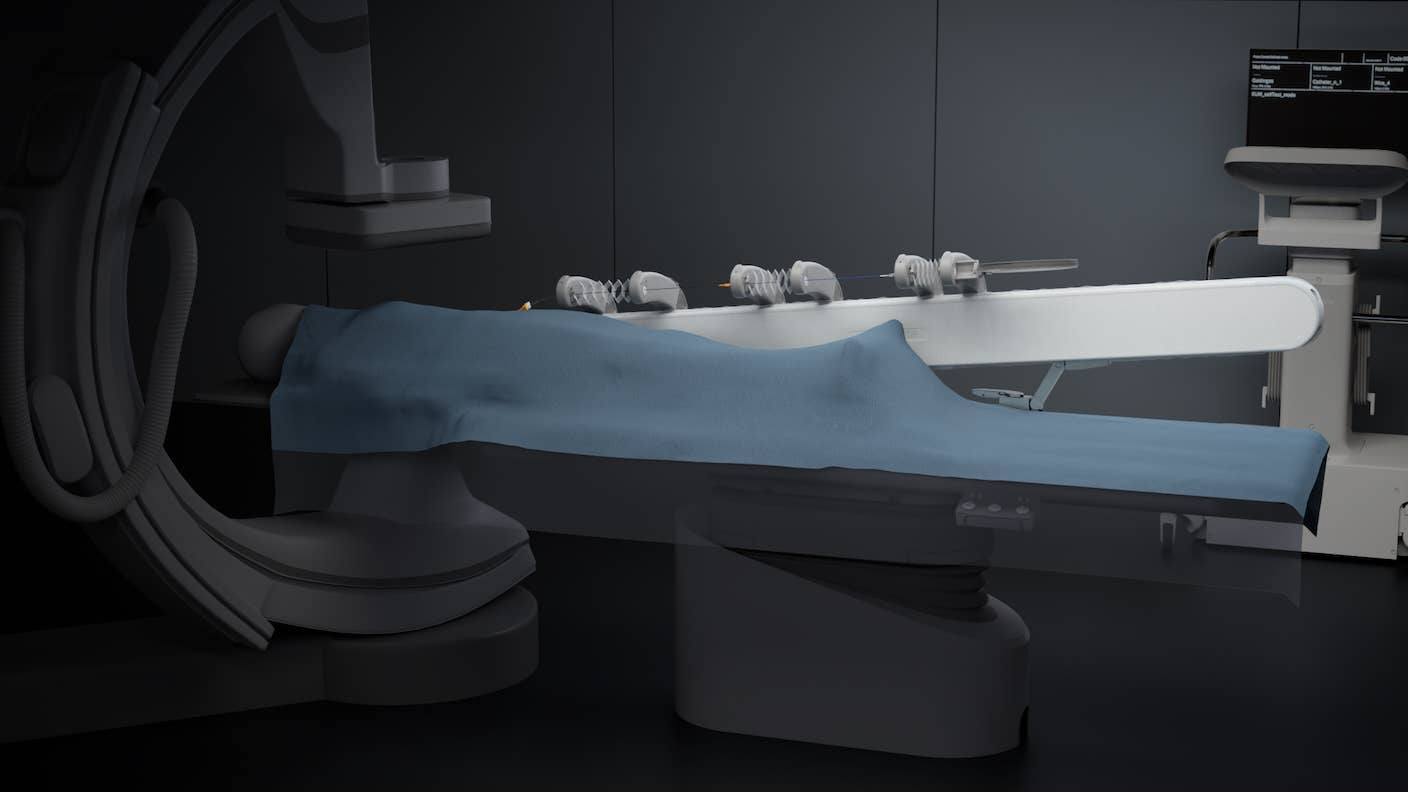

In Wild Experiment, Surgeon Uses Robot to Remove Blood Clot in Brain 4,000 Miles Away

A Squishy New Robotic ‘Eye’ Automatically Focuses Like Our Own

What we’re reading