The Era of Brain-Based Law through the Eyes of David Eagleman

Share

Law is the distilled essence of the civilization of a people, and it reflects people's soul more clearly than any other organism. - A.S Diamond, the Evolution of Law and Order

Accelerating technologies will undoubtedly challenge the basic assumptions of the mainstream culture and help shape our future values. Consequently, the legal system must adapt to reflect a new paradigm. In the following video, David Eagleman, a Baylor College of Medicine neuroscientist, discusses how our ever-expanding knowledge of the human brain may require an adjustment in our laws. If you think Dr. Eagleman is addressing these issues too soon, think again. Brain scan evidence already edged its way into an Indian murder trial, foreshadowing the use of neuroimaging in determining culpability and rational sentencing. He also touches on perhaps the greatest concern, the ethical implications of generating consciousness de novo in machines. How will our laws deal with AI? Overall, these scenarios will force us to critically assess our value system so that society can sustain its moral footing through an era of great technological change.

In his lecture at the Royal Society of the Arts, Dr. Eagleman opens with the case of Charles Whitman (2:17), the student who went on a murder spree at the University of Texas-Austin in 1966. Following an autopsy, doctors discovered a tumor impinging upon his brain’s amygdala, prompting neurologists to consider that biologically-based dysfunction led to the tragedy. Dr. Eagleman provides additional cases of malfunctioning brains and abnormal behavior (i.e. a frontal lobe tumor causing a man to express pedophilic tendencies (4:07), Parkinson’s medication inducing compulsive gambling (5:12)). He compares these cases to automatisms, a legal concept that protects defendants if they had no control over their actions. For example, alien hand syndrome is a neurological condition in which the hand executes movements without the will of the subject. Under the automatism legal defense, if an uncontrolled hand pushes someone off a cliff, the individual isn’t held liable.

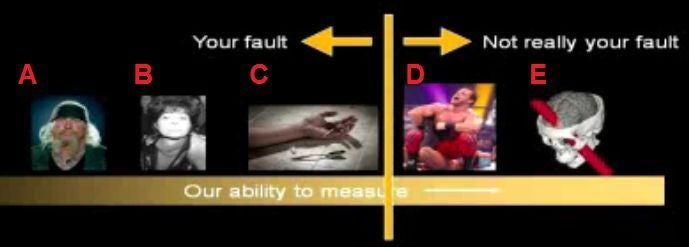

So is all criminal behavior the product of neurally-based automatisms decoupled from the will of the subject? Are we supposed to blame the person or the brain? Dr. Eagleman finds the distinction between the brain and the self to be arbitrary and based on false assumptions. In short, we are our brain. He explores this issue further at 15:48, introducing the continuum of culpability. Conditions on the far right include people with obvious damage like Phineas Gage, the perturbed man who had an iron rod lodged in his skull. Those on the far left include the “common criminal”, where the dysfunction is subtle, complex, and currently hidden from science. The line demarcates society’s present perspective on whether to blame individuals for their brain-based criminal activity, and its location is primarily determined by the available technology and our extant knowledge of brain function. According to Dr. Eagleman, this line will be pushed to the left as our understanding amasses.

Are we exonerating every criminal that has ever lived? Well, that depends if or when we ever find the neural correlates of free will. In the mean time, Dr. Eagleman thinks that these questions are irrelevant from a legal standpoint. He adopts a utilitarian stance, positing that the only useful aim of the legal system is to decrease the frequency of criminal behavior, not to dole out blame. Starting at 18:08, he discusses the role neuroscience can play in rational sentencing. In his opinion, prison sentences should be based solely on the probability of recidivism, and he notes that risk assessments based on surveying pedophiles are already influencing prison sentences. It’s not much of a stretch to see that brain scans will be employed in the future to ascertain the likelihood of criminals becoming repeat offenders.

On this point, Dr. Eagleman and I have somewhat diverging opinions. Although, criminal law is technically intended to mediate conflicts between individual entities and the state, other parties are almost always involved. Typically, families of the murdered and abused have interests that align with the government, but this may not always be the case with strict rational sentencing. Dr. Eagleman briefly mentions the behavioral phenomenon of altruistic punishment in which individuals relinquish resources to see others disciplined. This behavioral trait could be evolutionarily viable by facilitating the psychological recovery of those affected by heinous acts. If our sentencing is to be truly utilitarian, we should consider that we may not be maximizing social benefit by focusing only on the interests of the state. If not, there could be unintended consequences, such as an increased prevalence of revenge killings (à la the Hatfield-McCoy feud).

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

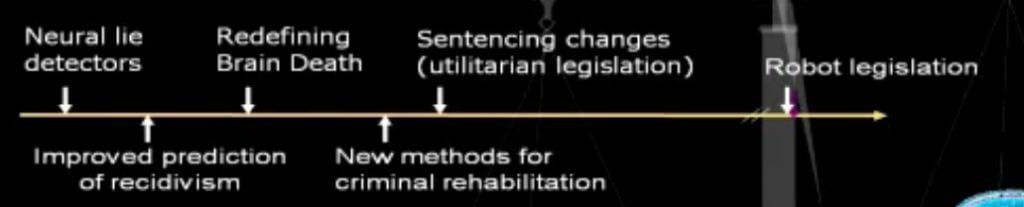

Toward the end of the lecture (33:13), he presents a timeline for the major breakthroughs in neuro-law. The most notable of these future milestones is undoubtedly the last one, robot legislation. He poses the question: if we create a “conscious” machine and turn off the power, does that count as murder?

Although Dr. Eagleman only briefly addresses this point, I believe the ethical and social implications of conscious machines dwarf those of brain-based sentencing. You could really teach a course on roboethics. Should machines with human or superhuman intelligence be subject to a special set of laws, or should there be an integrated legal system for humans, robots, and hybrids? In order to provide an answer based on a solid ethical foundation, we must first answer a question our species has been dodging for quite some time: at what point does something have the moral status of a human? We obviously have a difficult time with this one, regardless of the cultural context. Americans have grappled with the issue of fetal rights, the Japanese have quarreled over organ transplants, and people the world over have argued for a heightened moral status of animals. If we continue to sit on this simmering problem, then it could boil over when human-like robots enter the scene. What can we do to prevent AI activists from passing out flyers on the street?

To sort through this conundrum, I think that adopting brain-based metrics would be the best approach. One could use the computational power of robots and human brains as a common determinant of moral status. However, there could be problems with this method because of Moravec's paradox, which points out that rudimentary abilities require more computation than high-level reasoning. In this case, the status of "sentient being" could include far more organisms and machines than most would like. Instead, we could look at the complexity of the structure itself to determine moral status, but this could present its own issues. What if a robot has an internal system that surpasses the human neocortex in complexity but lacks the computational correlates of empathy? It seems that until we tease apart the components of the brain that make us human in the eyes of the law, determining the moral status of machines is a fool's errand. Fortunately, according to Dr. Eagleman's chronology, we have ample time to work this out.

Dr. Eagleman's insights about the brain pose a serious challenge to the legal community. Neuroscience is shattering the basic assumptions of legal theory, and it will be a long time before our laws are compatible with our knowledge of brain function. It's likely that we'll see major court battles, and maybe even a Supreme Court case, that use fMRI images as evidence. Hopefully, the judicial system will build a comprehensive body of precedents and our legislatures will pass rational laws that help us deal with criminal behavior using evidence-based approaches. After the dust has settled, we can prepare for the legal ramifications of advanced AI. On the other hand, I might have too much confidence in our politicians.

[Image Credits: The Salk Institute, iStockphoto (modified), RSA Presentation]

[Video Credit: The Royal Society of Arts (RSA)]

[Source: The Royal Society of Arts (RSA)]

Related Articles

Researchers Break Open AI’s Black Box—and Use What They Find Inside to Control It

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

Scientists Want to Give ChatGPT an Inner Monologue to Improve Its ‘Thinking’

What we’re reading