Hold Off On That Glass Just Yet – Red Wine Researcher Charged With Falsifying Data

Share

After being charged with 145 counts of fabrication or falsification of data, I'm thinking UConn researcher Dipak Das is a glass completely empty kind of guy.

The next time you toast a Cabernet Sauvignon to your heart health, you might be better off just toasting Tim Tebow. The much-touted health benefits of red wine took a hit recently. Dipak Das, a University of Connecticut researcher who has published extensively on the positive effects of resveratrol, was found guilty on 145 counts of fabrication and falsification of data published in 11 different journals. The university has slapped Das with a freeze on all of his NIH funding and has declined two grants that were to be awarded to Das totaling $890,000. They also notified the 11 journals about the charges.

The investigation, like Das’s work, has been messy. His CV is pretty impressive. His name shows up on 588 research articles in a Google Scholar search, and he is also the director of UConn’s Cardiovascular Research Center. That’s a big guy to take down, and Das wasn’t going down without a fight. The investigation was launched in 2008 following an anonymous tip of “research irregularities.” In July 2010 Das painted the investigation as a racial vendetta. “I became the Devil for the Health Center, and so did all the Indians working for me,” reports Medscape. In 2010 he suffered a stroke and was handed the report while in the hospital, being told he had four days to respond, according to a letter he wrote that was included in the report. He blamed the stress brought on by the investigation for causing the stroke. Following the recent charges various media sources have tried to contact Das but were unsuccessful. Apparently he’s returned to India to weather the storm from afar.

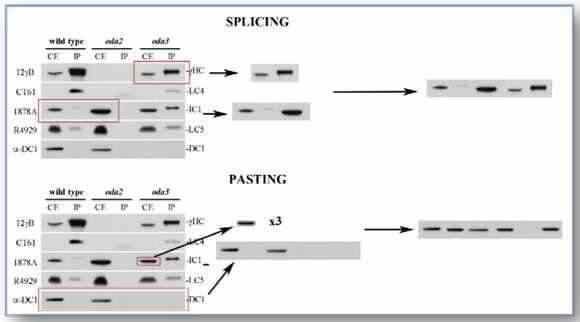

Das’s research focused on proteins called sirtuins thought to give resveratrol its beneficial properties. The investigation report, about 60,000 pages long, included altered images from “Western blots,” a technique used to measure amounts of protein. Someone had cut-and-pasted the protein blots on the images.

For his part, the report shows, Das can’t be sure who in his lab made what images: “The major problem is I don’t even remember what happened approximately 10 years ago and who did what,” he wrote in a letter to the Dean of the UConn Health Center. Not good enough, deemed UConn’s Special Review Board: “In response to the SRB’s draft report, and its addenda, Dr. Dipak Das provided no substantive information which could have explained the irregularities found by the SRB in this investigation.” A summary of the report can be found here.

Other researchers in the field are quick to point out that while the charges might mean the end of Das’s career, resveratrol research is alive and well. Studies in yeast and flatworms has shown resveratrol to increase longevity, and studies in mice have shown resveratrol to have anti-cancer effects and to suppress Alzheimer’s Disease. Other research suggests resveratrol can help reduce the risk of inflammation, blood clotting, and prevent obesity. Even if Das’s work cited by the investigation is retracted, argues David Sinclair, a Harvard Medical School researcher who also studies resveratrol, it won’t have a significant impact on the field as a whole.

Which brings up an important distinction. There’s a difference between figures in a research article and the actual data. Scientists will quantify changes in protein levels, for example, but show the prettiest image they have to visually convey those changes in the paper. So even if you falsify an image but your data is solid, you can still stick with your scientific claims (although your intelligence could be fairly questioned).

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

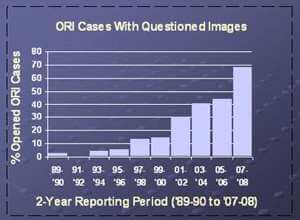

Papers and grants are submitted electronically these days, making them more susceptible to alterations with programs like Adobe Photoshop. Thus, image manipulation has become a growing problem that the Office of Research Integrity, part of the US Department of Health & Human Services, has had to increasingly deal with. Their website has a section that reads like a crimebeat, listing research misconduct case summaries back to 1994. The ORI has been using technologies, called “Forensic Actions,” that automate examination of digital images. Unscrupulous researchers beware.

Das’s manipulation is not an isolated incident in the world of scientific research. And I’m not even talking about Woo Suk Hwang and his fictitious stem cell research. I’m talking about the average, everyday researcher at your local university. A study performed in 2008 analyzed the figures on 35 papers published in the journals PLoS Biology and PLoS Medicine in a two-month period. They found 5 images that had been tampered with in 3 papers. When they looked at 13 papers for the entire year (don't ask me why only 13) they found another 5 problematic images in 3 separate papers. Probably similar to what Das had done, they found Western blots in which parts of one blot had been copied and pasted onto another Western blot. In another example they found that two gel images had been spliced together to make one. These sorts of manipulations are not strictly illegal. However, the authors of the paper must explicitly state any kind of modifications which have been performed. Of course, they didn’t in these cases for obvious reasons.

The investigation also uncovered some questionable emails. One email mentioned a “corrected picture,” according to the CT Mirror. In another email, one of Das’s students notified him, “I have changed the figures as you told me.” These emails don't look to me so out of the ordinary – sometimes the font size on the Y-axis is a little too small – but given the investigation’s unordinary findings….

One of the great things about science is that you can’t fake it for long. When Robert Milikan measured the charge of an electron in his historic oil drop experiment he got a value that was too low due to an incorrect value for air viscosity. Plotting the data gotten by others trying to replicate his experiment in the following years shows a progressive march upward in electron charge values. Was the electron charge increasing over time? Of course not. When they got a value that was too high above Milikan’s – the correct value – they searched for ways to explain their “error” and didn’t report the data. Values close to Milikan’s, however, were readily reported. Although it took longer than it should have, the value increased until finally settling on the true value of an electron charge. The truth found its way despite human bias. The more people like Das and Hwang are weeded out, the better off science will be. But in the end it won’t matter because nature will always, eventually find a way to shine through our biased, ignorant, inaccurate, dishonest, greedy minds.

Cheers to that.

[image credits: University of Connecticut Special Review Board, NY Times, and Nature]

image 1: western blot

image 2: das

image 3: graph2

Peter Murray was born in Boston in 1973. He earned a PhD in neuroscience at the University of Maryland, Baltimore studying gene expression in the neocortex. Following his dissertation work he spent three years as a post-doctoral fellow at the same university studying brain mechanisms of pain and motor control. He completed a collection of short stories in 2010 and has been writing for Singularity Hub since March 2011.

Related Articles

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

Hackers Are Automating Cyberattacks With AI. Defenders Are Using It to Fight Back.

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through March 7)

What we’re reading