Red Meat Is Bad For Your Heart, But Possibly For A Previously Unknown Reason

Share

You knew that too much red meat wasn’t good for you, but maybe you didn’t know the whole story.

High in saturated fat and dripping cholesterol, many a meat lover has either accepted the risk for heart disease and continued to mow down or heartbreakingly changed their ways. A new study adds another sour ingredient to the recipe. It’s been known that carnitine helps to transport fatty acids into cells where they can be metabolized for energy. But a recent study has shown that the normally do-good carnitine can be made to do bad things for the heart. And red meat is full of carnitine.

Previous research has shown that carnitine can be converted by microbes in the gut to the substance trimethylamine-N-oxide, or TMAO, which causes atherosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries. Atherosclerosis can lead to heart attack, stroke, and death.

To gauge the effects of carnitine in the diet, the study measured both the intake of carnitine and the levels of TMAO in the blood, and checked for associated risk for cardiovascular disease. It involved 2,595 patients under evaluation for heart-related conditions. Based on their diets, the patients were divided into three groups: omnivores, vegans and vegetarians. They found that diets high in carnitine showed a higher risk for heart attack, stroke and death, but only when those diets were accompanied by high levels of TMAO.

![New study shows carnitine, found in many dietary supplements, raises the risk of cardiovascular disease. [Source: Wikipedia]](https://singularityhub.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/image3A2.jpg)

New study shows carnitine, found in many dietary supplements, raises the risk of cardiovascular disease. [Source: Wikipedia]

Baseline levels of TMAO were higher in omnivores than in vegans and vegetarians. And even when they gave vegans and vegetarians doses of carnitine, their bodies produced lower amounts of TMAO compared to their meat eating counterparts.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The reason for the difference appears to lie in the different profiles of gut bacteria. “The bacteria living in our digestive tracts are dicated by our long-term dietary patterns," Stanley Hazen, chief of cellular and molecular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic’s Lerner Research Institute and lead author of the study, said in a press release. “A diet high in carnitine actually shifts our gut microbe composition to those that like carnitine, making meat eaters even more susceptible to forming TMAO and its artery-clogging effects. Meanwhile, vegans and vegetarians have a signficantly reduced capacity to synthesize TMAO from carnitine, which may explain the cardiovascular health benefits of these diets.”

In a separate experiment, the researchers gave food to mice supplemented with carnitine. They saw TMAO levels spike and the risk for atherosclerosis in the mice doubled.

We’ve always been told that reducing our intake of saturated fat reduces the risk for cardiovascular disease, but a study performed in 2010 turned that idea on its head. Amazingly, the meta-analysis that included data from 347,747 subjects found no link between the amount of saturated fat a person ate and risk for cardiovascular disease.

And while carnitine is not an essential nutrient – our bodies produce enough of it – it is found in a number of dietary supplements used to build muscle and boost energy. Because of the widespread use of these products, Hazen argues, research into a possible link between carnitine supplements and cardiovascular disease is something that needs to be studied more.

So, in the end, the message remains the same, even if it’s not the saturated fat we need to worry about, but the carnitine. Nothing changes for the omnivores, vegans and vegetarians out there. That is, unless the more health-minded are bolstering their performance with protein shakes and energy drinks.

Peter Murray was born in Boston in 1973. He earned a PhD in neuroscience at the University of Maryland, Baltimore studying gene expression in the neocortex. Following his dissertation work he spent three years as a post-doctoral fellow at the same university studying brain mechanisms of pain and motor control. He completed a collection of short stories in 2010 and has been writing for Singularity Hub since March 2011.

Related Articles

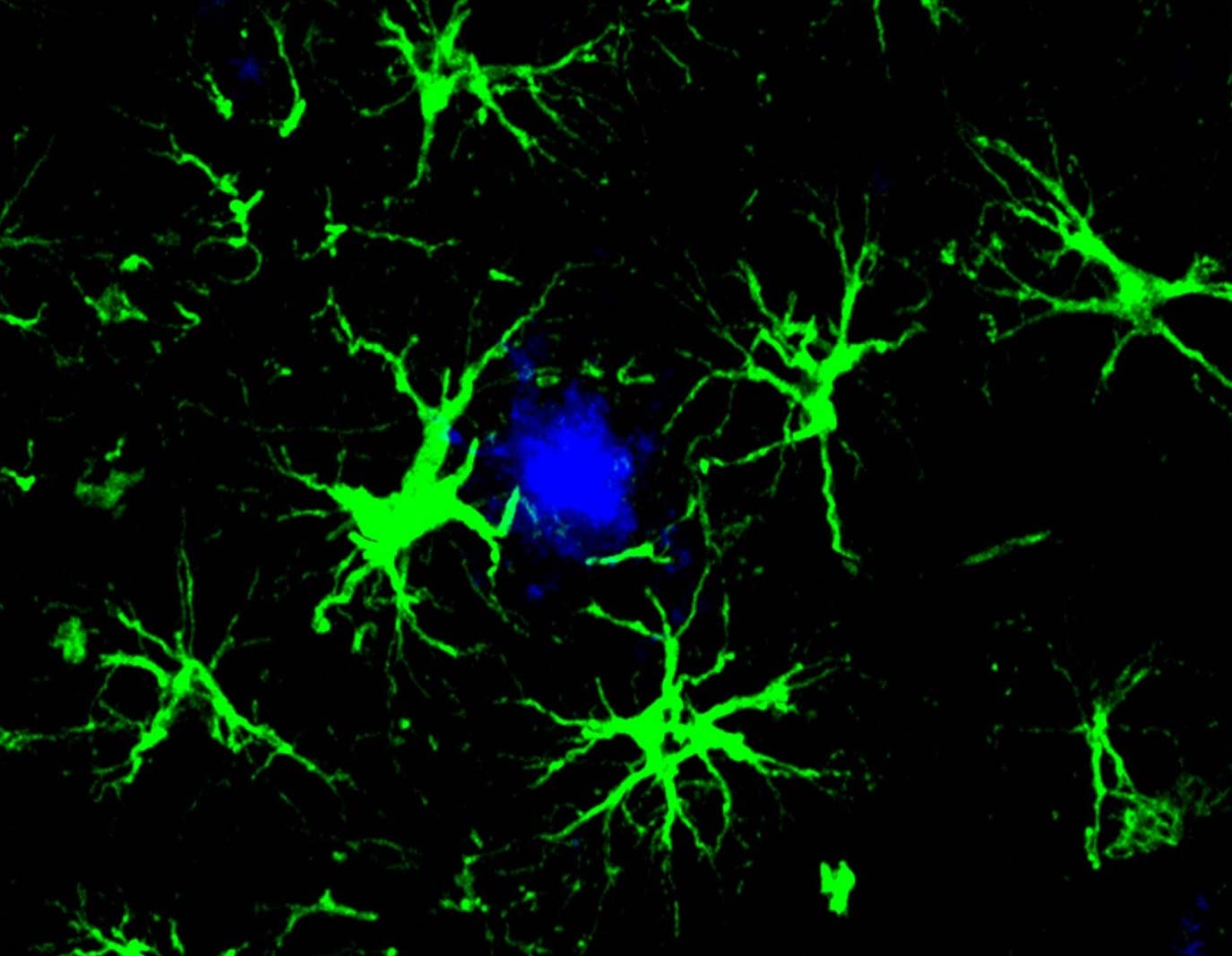

These Genetically Engineered Brain Cells Devour Toxic Alzheimer’s Plaques

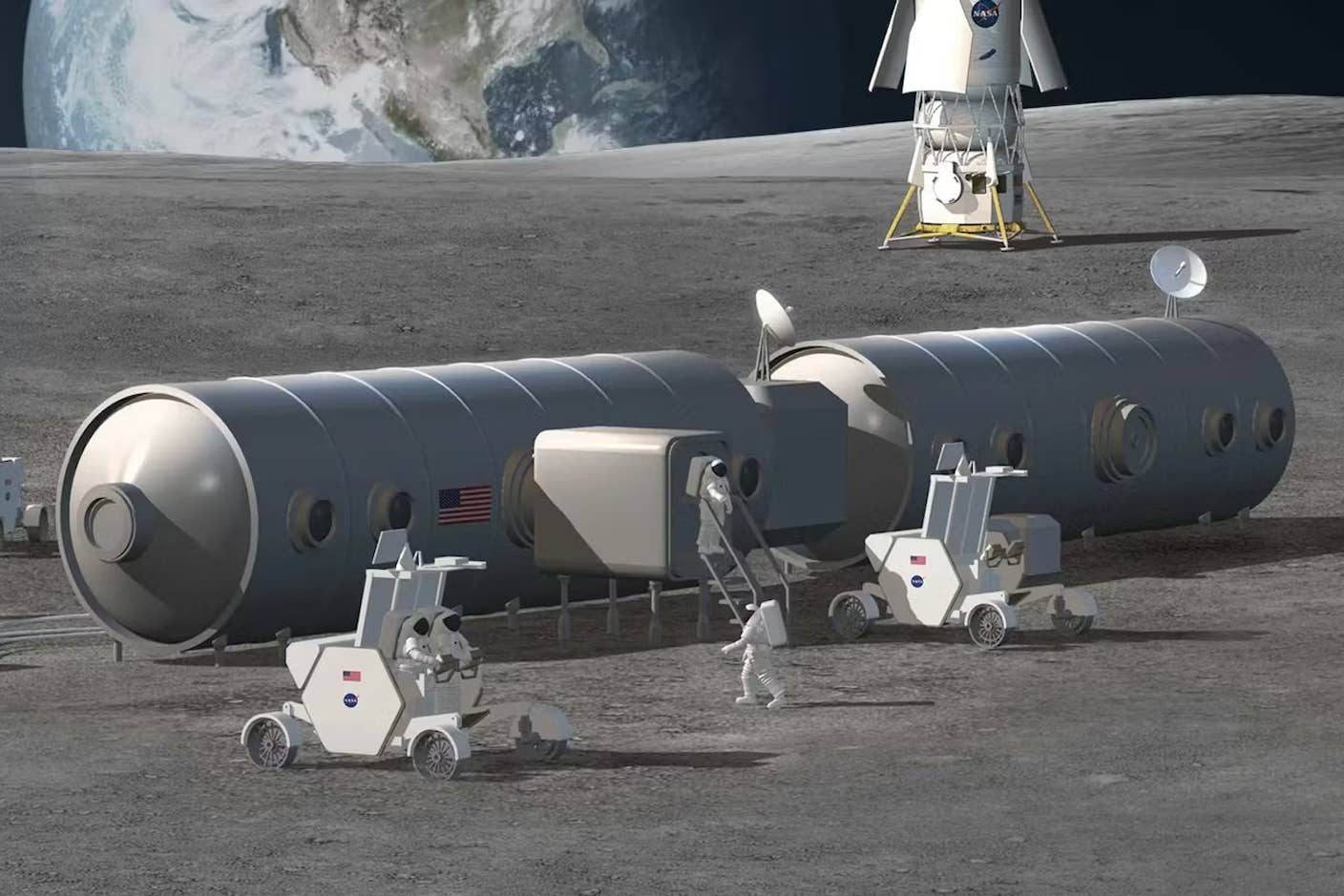

The US Plans to Break Ground on a Permanent Moon Base by 2030. Here’s What It Will Take.

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

What we’re reading

![[Source: Wikipedia]](https://singularityhub.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/image2A3.jpg)