Two Boston Patients Free of HIV After Bone-Marrow Transplant

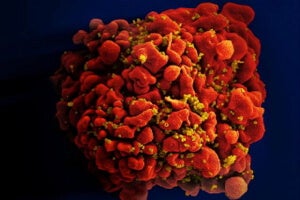

In June, at the 2013 International AIDS Society conference, medical researchers made an extraordinary announcement. Two HIV positive cancer patients are HIV-free after undergoing bone marrow transplants. The patients have been off anti-retroviral drugs for seven weeks and fifteen weeks respectively, but doctors are, as yet, hesitant to call them cured. The virus may yet reemerge at a later date.

Share

In June, at the 2013 International AIDS Society conference, Dr. Tim Henrich made an extraordinary announcement (13:50 in the video below). Two HIV positive cancer patients are now HIV-free four years after undergoing bone-marrow transplants. Though Henrich was hesitant to declare a full victory, as the virus may yet reemerge—it's a hopeful bit of news and another clue in the long and vexing search for a cure.

The beginning of this story dates back to 2009, when researchers made a similar announcement about a different subject. Widely known as the Berlin patient, Timothy Brown had been given two bone marrow transplants to rebuild his immune system after undergoing extensive chemotherapy and radiation to combat leukemia.

The transplants contained stem cells from a donor with an HIV-resistant genetic mutation called delta 32. The cellular receptor, CCR5, is the gateway through which HIV invades white blood cells. Men and women with the delta 32 mutation, around 1% of the population, lack the CCR5 receptor and are therefore resistant to most forms of HIV.

Remarkably, Brown not only survived leukemia and three rounds of chemo, but he emerged HIV-free. Researchers were careful to look anywhere the virus might be hiding, even taking brain and spinal fluid samples.

Five years on, the virus is, quite simply, gone.

Brown's case verges on the miraculous, beating both AIDS and cancer—at the same time. And it was thought the rare delta 32 mutation was a necessary ingredient. But if verified, the Boston cases may show anti-retroviral drugs are just as effective.

In contrast to Brown, both Boston patients suffered from lymphoma, not leukemia. Each underwent a more moderate round of cancer therapy and needed a less complete bone marrow transplant. Critically, neither received stem cells with the delta 32 mutation, but both remained on anti-retrovirals during the transplant and for some years thereafter.

Then recently, following months of tests to confirm the virus was still missing in action, the patients' doctors took them off the anti-retroviral drugs. Seven weeks and fifteen weeks on, respectively—there's still no sign of HIV.

How do researchers explain the result?

Brown's immune system was so compromised, he couldn't continue anti-retrovirals. But the stem cells with the delta 32 mutation kept the virus from spreading while simultaneously targeting and destroying the few remaining HIV-infected cells.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Though the Boston patients weren't given stem cells with the delta 32 mutation, they were healthy enough to continue a course of anti-retrovirals. The drugs may have mimicked the cells with the delta 32 mutation by preventing the virus from spreading. Meanwhile, healthy new cells from the bone-marrow transplant eradicated the old, weakened HIV-infected cells—and every remaining virus along with them.

The finding offers a ray of hope for those suffering from the disease. The Boston cases show less destructive therapy may yield similar results to those achieved by Brown. Indeed, while Brown still suffers weakness and pain from his treatment, the Boston patients reportedly “feel great and are leading completely normal lives.”

Researchers remain only cautiously optimistic, noting that, generally, the virus can reemerge after 50 days—or about the length of time the patients have been off anti-retroviral drugs—but it can also take longer, up to six months or a year. Though the results so far are promising, they'll withhold final judgment for awhile yet.

And even if, like Brown, the patients do remain HIV-free, the procedure won't likely be replicated terribly often. Bone-marrow transplants and anti-retroviral drug therapy require access to top (expensive) medical care and a donor match for the stem cells.

Further, bone-marrow transplants are very risky. A third Boston patient died in treatment, and in general, there is a 15 to 20 percent risk of death. Brown’s procedure carried a 40 percent risk of death.

In an age when the right drug cocktail can make life livable for folks with HIV, the only ethical candidates for the treatment would be those who are diagnosed with cancer as well as HIV—not exactly a cure for the masses. Not yet, at least.

Image Credit: Nissim Benvenisty/Wikimedia Commons, NIAID/Flickr

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

Researchers Break Open AI’s Black Box—and Use What They Find Inside to Control It

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 21)

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

What we’re reading