Scientists Ponder Human Role in Mid-Atlantic Dolphin Die-Off

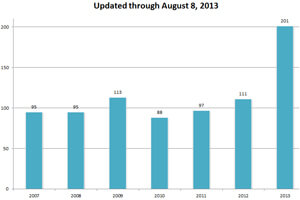

The number of bottlenose dolphins beaching themselves along the Mid-Atlantic coast skyrocketed in July and early August, leading the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to declare on August 8 an “unusual mortality event” and launch an investigation into what might be causing the deaths.

Share

As our human footprint on the planet grows heavier, our activities may have complex and unforeseen effects in far reaching places like the oceans.

In one ongoing instance, the number of bottlenose dolphins beaching themselves along the Mid-Atlantic coast has skyrocketed this summer. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has declared an "unusual mortality event," launching an investigation into what might be causing the deaths.

Since July roughly 70 dolphins stranded themselves on Virginia beaches. In previous years, the state has seen less than a dozen dolphin strandings during the summer months. New Jersey, which sees even fewer strandings in a typical July, was the site of 20 dolphin deaths last month. More than the usual number of dolphins have also beached this summer in New York, Delaware and Maryland, according to the NOAA. All told, nearly 150 dolphins have died.

The stakes of the episode are high because the deaths are reminiscent of a 1987-88 die-off that claimed nearly 800 bottlenose dolphins from the same Mid-Atlantic population. That episode, which caused the same mid-Atlantic dolphin population currently affected to be labeled "depleted," ultimately prompted Congress to create the unusual mortality event protocol that was invoked on August 8.

“The timing of it all on the 25th anniversary, with the same species at the same time of year in the same geographical area has people really alarmed,” Trevor Spradlin, a marine mammal biologist with the NOAA’s Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program, told Singularity Hub.

Marine mammals, and bottlenose dolphins in particular, have paid a high price for human industrialization. The dolphins — Flipper's species — are among the most frequent victims of unusual mortality events. Die-off events appear to have increased globally since the late 1980s, in some cases spurred by disease or by toxins produced by algae that flourish in polluted waters.

On the west coast, bottlenose dolphins have been among the marine mammal species likely impacted by the Navy’s use of sonar. In the Gulf of Mexico, the animals were seriously affected by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010. (According to an NOAA report, “Coastal dolphins have been observed with tar balls attached to them and seen swimming through oil slicks close to shore and inland bays.”) On the east coast, the dolphins frequently get snagged in fishing nets, according to the NOAA.

The bottlenose dolphin die-off in the late 1980s was eventually attributed to morbillivirus, a virus related to the one that causes the measles in humans. A virus may be behind the current die-off, as well.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

“Based on the rapid increase in strandings over the last two weeks and the geographic extent of these mortalities, an infectious pathogen is at the top of the list of potential causes for this unusual mortality event, but all potential causes of these mortalities will be evaluated,” an NOAA statement said.

Preliminary testing suggests that one of the beached dolphins was infected with the morbillivirus, which can cause skin lesions and pneumonia. Several animals also presented with evidence of pneumonia.

"Anything like that is going to be a red flag,” said Spradlin. “We want people to be aware that if this is going to be a repeat of 25 years ago, it could have very serious implications for that stock of dolphins."

The morbillivirus was only identified in dolphins and other cetaceans in the late 1980s. Researchers don't know if it is spread or exacerbated by human activity — for instance, if certain types of pollution might lower the dolphins' immune response, leaving them more susceptible to the virus. Morbillivirus could also simply hit upon particularly lethal variants from time to time, like the flu.

Tissue samples collected from the dead animals must be analyzed before researchers can say with any certainty that the deaths are attributable to a virus, or whether bacteria or chemical pollutants or even acoustic trauma may be to blame, Spradlin said.

"As we find out more information about the cause or causes, we can try to implement particular measures to quiet it down, hopefully. But if it’s Mother Nature there may be little we can do," said Spradlin.

The NOAA will post any updates on its investigation into the bottlenose dolphin deaths on its website.

Photos: Dominic Sherony via Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Meta Will Buy Startup’s Nuclear Fuel in Unusual Deal to Power AI Data Centers

Your ChatGPT Habit Could Depend on Nuclear Power

Hugging Face Says AI Models With Reasoning Use 30x More Energy on Average

What we’re reading