Study Suggests Copper May Be the Culprit in Alzheimer’s Disease

Researchers from the University of Rochester have pursued an increasingly common hypothesis that copper consumption may play a role in triggering Alzheimer’s disease. In findings published August 19 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, they showed that exposing the brain to copper not only spurs the production of the amyloid beta protein that characterizes the brains of Alzheimer’s sufferers, but also slows the brain’s efforts to clear out the plaque.

Share

Recent research on Alzheimer’s disease suggests that the illness may be more common than previously thought, especially in advanced old age. With life spans extending, research into the prevention and treatment of the disease has become that much more important.

Researchers from the University of Rochester have pursued an increasingly credible hypothesis that copper consumption may play a role in triggering Alzheimer’s disease. In findings published August 19 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, they showed that exposing the brain to copper not only spurs the production of the amyloid beta protein that characterizes the brains of Alzheimer’s sufferers, but also slows the brain’s efforts to clear out the plaque.

“It is clear that, over time, copper’s cumulative effect is to impair the systems by which amyloid beta is removed from the brain. This impairment is one of the key factors that cause the protein to accumulate in the brain and form the plaques that are the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Rashid Deane, the study’s lead author.

Copper — which is found in foods including red meats, shellfish, nuts, seeds and tap water carried in copper pipes — can break the blood brain barrier, which controls what enters and exits the brain, interfering with the organ's healthy cellular processes.

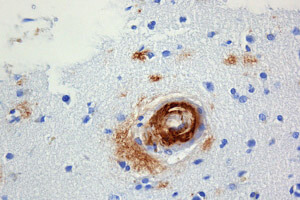

Researchers gave mice water that contained just a fraction of the amount of copper that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has deemed safe for human consumption. They observed that the copper accumulated in the walls of the capillaries that feed into the brain, eventually damaging the protective barrier they offer the uber-organ. In mice that had been genetically altered to posses a genetic trait linked to early onset Alzheimer’s disease, but not in normal mice, the copper actually penetrated the barrier.

The researchers observed that, when exposed to copper in this way, brain cells increased their production of amyloid beta, a byproduct of cellular activity that a healthy brain can flush out. Copper also interacted with the amyloid beta, causing it to form larger chunks which were more difficult for the brain to clear out.

“It’s like a double whammy. That hints that copper may contribute to the progression of the disease,” Deane told Singularity Hub.

Indeed, the mice with the genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease exhibited cognitive deficits relative to the control group after their exposure to copper.

As for how a vital nutrient like copper could also be a cause of a disease as ravaging as Alzheimer’s, the results are too preliminary to say. The researchers emphasize that individuals should not dramatically reduce their copper consumption.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

"There is some hint that too much of a good thing could be bad, but too little of a good thing is bad as well," Deane said.

British scientists concluded that copper, to the contrary, helps guard against Alzheimer's disease, in findings that Deane attributed to the dramatically different concentrations of copper used.

But quantity is not the only factor that could account for copper's seemingly paradoxical role in the body. Copper in tap water is much more quickly absorbed than the copper in food. Some people may also be more susceptible to the effects of copper on the blood brain barrier, Deane said.

While the first result of this study may be the removal of copper from dietary supplements, the findings also encourage early-stage efforts to treat Alzheimer’s with compounds that bind to copper and control its activity in the body. Ongoing trials of one such compound, PBT2, have shown some promise.

But, given the number of treatments that have failed to improve Alzheimer’s symptoms, the Rochester team’s immediate goal is merely to slow the progression of the disease.

“We have no treatment right now, so you have to think of something else. Prevention is also tough, since aging is a risk factor and everybody ages. So maybe we can delay the onset of it a little bit,” Deane said.

Images: Jurii, National Institute on Aging and Marvin 101 via Wikimedia Commons

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

What we’re reading