Fleets of Robots Take To the Sea, Autonomously Collecting Data

Autonomous robots are plumbing the ocean’s depths with increasing regularity. This hurricane season, a research project called GliderPalooza 2013 deployed some twelve sea drones to take a snapshot of the mid-Atlantic ocean. Ocean-going robots can go where humans can’t, are cheaper than ships, and easier to maintain than buoys. Combined traditional data sources, scientists are piecing together an increasingly complex map of the ocean.

Share

Autonomous robots are plumbing the ocean’s depths with increasing regularity. This hurricane season, a research project coordinated by Rutgers University (GliderPalooza) deployed over a dozen sea drones to take a snapshot of the mid-Atlantic ocean.

Ocean-going robots can go where humans can’t. They're cheaper than ships and more dynamic than buoys. Combined with these and other traditional data sources, like satellites, scientists are piecing together an increasingly complex map of the ocean.

“We’re seeing the ocean like we haven’t seen it,” Michael Crowley, a participating marine scientist from Rutgers, told the New York Times.

In addition to cost and maintenance benefits, the project’s drones, mostly a variety called Slocum gliders, aren’t restricted to surface data—they can produce a more fully three dimensional image of the ocean.

Each $125,000 to $150,000 drone dives in an arc 650 feet beneath the surface to measure conditions like salinity (salt content), temperature, and oxygen. The battery-powered drones are slow but low-energy, taking in and expelling seawater to change their depth—this vertical motion is converted into forward motion by the drone's wings.

Surfacing every two to three hours, each drone relays data by satellite to mission control at Rutgers. They can stay at sea, operating autonomously, for months at a time.

Because these rugged robots can handle harsh environments humans can't, they're able to collect important and elusive data, like water temperature inside a hurricane--a key driver of storm intensity. “The ocean is your heat driver. It’s your engine for hurricanes,” Travis Miles, a Rutgers PhD student, recently told Salon.

The same Rutgers researchers coordinating GliderPalooza also had gliders in Hurricanes Irene and Sandy. They're still crunching the data, but water temperatures are providing clues explaining why Irene was milder than predicted, while Sandy's storm surge dangerously outstripped expectations.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

“In Hurricane Sandy, you can see the bottom temperatures off of New Jersey went from 10 degrees Celsius to near 18 degrees Celsius,” Miles said. Cooling water temperatures during Hurricane Irene, on the other hand, made the storm less intense as it approached land. Such information may in the future help us better prepare for storms.

Though there were more gliders in the Atlantic this hurricane season, the season itself was historically quiet. Meanwhile, in the Pacific, where the team is planning to deploy more gliders, Typhoon Haiyan wreaked havoc in the Philippines.

According to Scott Glenn, co-director of Rutgers' Coastal Ocean Observation Lab (COOL), "If we can better predict the intensity, we can better predict the human impact, and that’s critical, especially in Asia, where so many people die when these typhoons make landfall.”

Beyond GliderPalooza, other ocean-going robots are contributing data.

Argo is an internationally funded net of ocean-going robots. Like the Slocum gliders in GliderPalooza, Argo's simpler robotic "floats" also dive for data. But Argo's $30,000 bots are cheaper, go deeper (6,500 ft), and span the world's oceans. The Argo fleet reached a target 3,000 deployed floats in 2007 and notched its millionth data point earlier this year.

In perspective, that's more data in just a few years than was gathered by ship throughout the entire 20th century. The more we know, the better our models, and hopefully, the better our ability to forecast extreme events.

Image Credit: NASA Goddard/Flickr (Typhoon Haiyan)

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

These Robots Are the Size of Single Cells and Cost Just a Penny Apiece

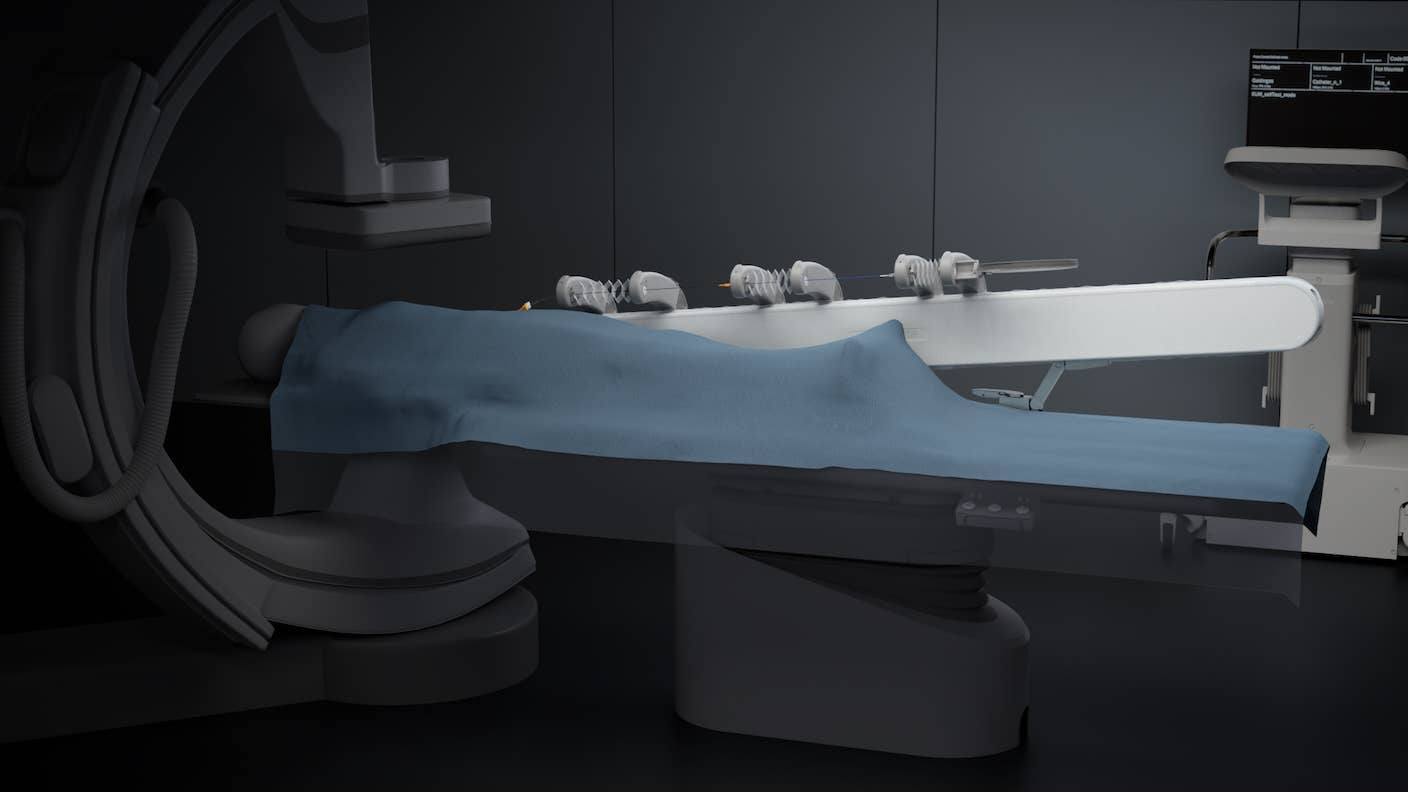

In Wild Experiment, Surgeon Uses Robot to Remove Blood Clot in Brain 4,000 Miles Away

A Squishy New Robotic ‘Eye’ Automatically Focuses Like Our Own

What we’re reading