Want a Cheap 2,000x Microscope? Just Fold This $0.50 Piece of Paper

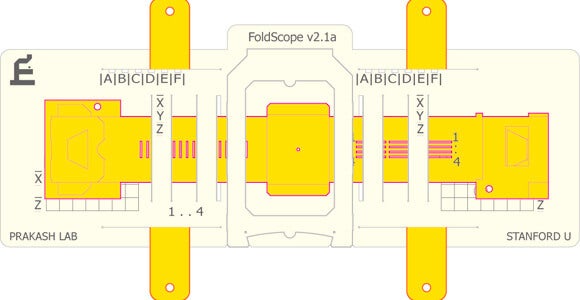

Stanford University physicist Manu Prakash has garnered attention for a microscope made of paper and assembled by folding in the origami style. Each device costs 50 cents and weighs less than 9 grams, even with a battery and LED light source built in.

Share

It’s an ironic marker of the digital divide that sometimes what constitutes a technological breakthrough is in fact a return to the simplest technologies in order to bring the benefits of modern science to those in the developing world.

To wit, Stanford University physicist Manu Prakash has garnered attention for a microscope made of paper and assembled by folding in the origami style.

The innovation of the design, called Foldscope, is radical access. The paper microscopes cost 50 cents and weigh less than 9 grams, even with a battery and LED light source built in. They are rugged enough to survive being stepped on, dropped from a 3-story building or immersed in water.

“Thinking about cost as an engineering constraint brings new life to old ideas (physics). This is what makes the difference between an idea influencing hundreds of people and a billion!” Prakash says of the work on his Stanford website.

And when it comes to infectious disease, access is the name of the game: Diseases for which cutting-edge treatments are available in affluent countries continue to spread and kill in less developed parts of the world.

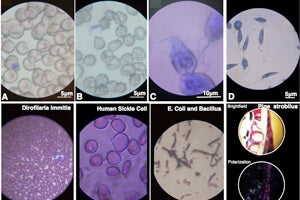

Foldscope offers 12 models of microscope, offering up to 2,000X magnification with resolution sharper than a micron. (An award-winning portable microscope developed in 2010 for poor and rural environments reached just 60x and drew on a mobile phone for power.) Each model is designed to detect a particular disease common in the developing world. A sketch on the back of each model identifies the bacteria or virus in question.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

For instance, the malaria model includes a fluorescent filter. There are also brightfield, darkfield, polarization and projection microscopes.

“This specificity improves the specificity and sensitivity of diagnostic tests done by field workers on a platform like Foldscope,” the project’s website explains.

Every model fits on an A4-sized piece of paper, slightly larger than letter size, in which LED and lenses are embedded. Roll-to-roll processing keeps the cost down and origami folding methods ensures that components line up exactly after assembly. The assembly takes about seven minutes, according to Prakash.

While Foldscope appears to be the first paper microscope, a company that grew out of Harvard research, called Diagnostics for All, makes paper laboratory tests. They are also designed to withstand the harsh conditions remote areas dish out.

The Foldscope microscopes are being field tested in Africa and Southeast Asia. Excitement about the paper scopes has also led Prakash to propose a crowd-sourced microscopy textbook written by and for the next generation of scientists. Ten thousand people around the world who make a case for what they could bring to the textbook project will get to beta test the microscopes.

Images courtesy Foldscope

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

This Portable Wind Turbine Is the Size of a Water Bottle and Charges Devices in Under an Hour

Mojo Vision’s New Contact Lens Brings Seamless Augmented Reality a Step Closer

The Weird, the Wacky, the Just Plain Cool: Best of CES 2020

What we’re reading