Google to Spend a Billion or More on Internet Satellites

Share

Internet access is common in the developed world, but many in emerging markets are just now getting online. For Google, one of the most visited sites in the world, it's a massive growth opportunity. And they aren't going to wait for local governments or anyone else to build the necessary infrastructure.

The Wall Street Journal recently reported the firm plans to spend $1 to $3 billion to launch a fleet of internet satellites. The satellite network would initially include 180 small satellites and might later double that number.

The project is part of Google’s wider plan to provide internet access to remote areas using solar powered drones and high altitude balloons. They recently purchased drone company Titan Aerospace and launched Project Loon to experiment with a squadron of stratospheric, internet providing balloons steered by global trade winds.

Why is a software company so interested in building infrastructure? A Google representative explained to the WSJ, "Internet connectivity significantly improves people's lives. Yet two thirds of the world have no access at all."

Consider the implications of the second half of that statement. Opening new markets is critical to revenue growth, and Google's got its eye on four billion potential new users.

The firm dominates search and operates the two most visited sites on the web (Google and YouTube). A healthy fraction of those billions may well choose Google's products—if only they can gain access to them.

Project Loon balloons like this one are part of Google's plan to broaden internet access from on high.

Mobile computing and wireless signals are likely to provide that access. Just as cell phones leapfrogged landlines, mobile internet (combined with affordable smartphones, like this one from Mozilla) may jump over wired internet connections in remote areas.

Because the reach of cellphone towers is limited by line of sight to local areas, getting up high provides wider coverage. Satellites are a traditional way to provide signal in rural places. But it seemed Google was trying to circumvent satellites with other out-of-the-box solutions like drones and balloons. Why? Satellites are expensive to build and deploy. Especially 180 of them.

The WSJ offers other earlier satellite projects as a cautionary tale.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Backed by Microsoft and telecom entrepreneur Craig McCaw, Teledesic likewise attempted to construct a network of internet providing satellites (and even considered drones too) in the 1990s but was forced by budget woes and technical challenges to abandon the $9 billion undertaking in 2002. Another 1990s project by Iridium Satellite LLC went bankrupt in 1998.

Roger Rusch, who runs satellite consulting firm TelAstra, told the WSJ Google’s satellites could cost up to 20 times more than their low-end estimate—more like $20 billion than $1 billion. "This is exactly the kind of pipe dream we have seen before." Rusch says the landscape is littered with failed satellite projects like the one being proposed by Google.

There isn’t anything cheap or easy about creating orbital infrastructure. But recent entrants into the satellite launch market, like SpaceX, are reducing the cost to launch satellites, even as the satellites themselves are getting cheaper to build. Tim Farrar, head of another satellite consulting firm TMF Associates, thinks Google might launch 180 small satellites for $600 million.

Of course, broadcasting internet is useless unless there are devices on the ground listening in. Mozilla (and others) are attempting to create affordable smartphones for emerging markets. And that’s where Google might step in with cheap service.

The firm is offering average speeds to Google Fiber subscribers free for seven years and gigabit speeds for the same fee you pay your cable provider. Maybe they would offer a similar deal to new customers in emerging markets—charging a fee to cover operational costs but subsidizing the price to maximize their user base (and to message Google = good).

Ultimately, Google providing internet in any market is a means to an end.

They'll have done exceedingly well if they convert any significant fraction of those four billion new users with a $1 billion investment (6% of quarterly revenue and a third the price of their recent Nest acquisition). Fact is, they could probably afford to spend more.

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

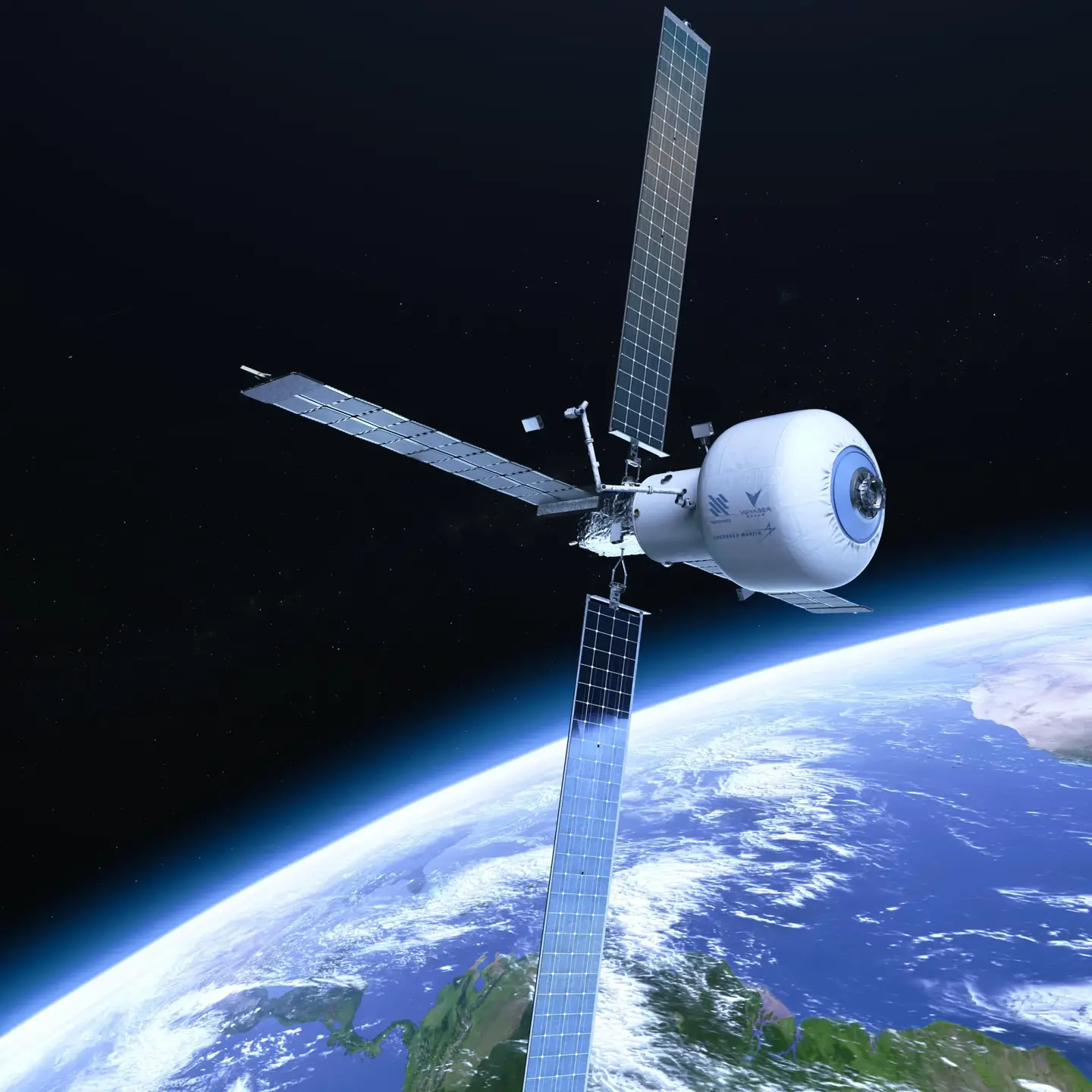

The Era of Private Space Stations Launches in 2026

What we’re reading