Anousheh Ansari on Her Journey to the ISS and the Endless Possibilities of Space

Share

“The biggest hurdle to a flourishing space industry is the cost of access to space, so if we can reduce that cost, the possibilities become endless.”

So said Anousheh Ansari, speaking to the participants of the 2014 Graduate Studies Program (GSP) at Singularity University about her story. Ansari is an Iranian-born engineer who is the first woman to pay her own way to the International Space Station (ISS). Today, she’s co-founder and chairwoman of Prodea Systems, an Internet of Things platform for the home.

Though she’s busy on the ground, she’s quick to point out that space is her lifelong passion.

As a child, Ansari dreamed of joining Starfleet Academy, but the dream took a detour when she realized one couldn’t just sign up to fly on the Enterprise. Instead, she launched Telecom Technologies, a telecommunications company co-founded with her husband and brother. Its successful acquisition in 2001 enabled the Ansari family to support the first X PRIZE with $10 million.

Yet, it wasn’t until 2006 that she achieved her dream of going into space.

She chronicled the experience of being in orbit in her blog capturing the wonder she felt:

You cannot see any borders… you cannot tell where one country ends and another one starts… the only border you see is the border between land and water...These are the most peaceful moments I have had in my life.

Recounting her journey to the GSP audience, Ansari stressed the importance of others experiencing the wonder of space, both for personal transformation and furthering innovation on Earth. Yet, communicating the message to the public has sometimes proven to be a challenge. Even today it is difficult for people to understand the importance of space exploration — many believe that going into orbit privately is just a way for rich people to ‘play’.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

"[The public] doesn’t realize that everything we do today is touched by space technology. Our communications systems, entertainment systems, weather and GPS systems, medicine, manufacturing — all these things have benefitted from space technology," she explained.

Along with Ansari, NASA also has been trying to educate the public about the varied aspects of our modern lives touched by the space program. Since the 1970s, NASA has documented 1,800 ‘spinoff’ technologies, many of which we benefit from to this day.

For example, memory foam, first used during the Apollo mission to ensure the command module and astronauts could be recovered safely, is now used in mattresses, shoe insoles, airplane seats, football helmets, and braces for injured animals. Another technology from that era, remote-controlled pacemakers, now helps avoid excessive surgeries. Finally, scratch resistant lenses were first developed when NASA engineers coated water filters in thin, plastic film, then further developed the tech for use as an abrasion-resistant coating on space helmet visors.

“And the path for the future is greater," said Ansari. "The whole goal of our work [with X PRIZE] was to reduce the cost of access to space.”

And that goal is well on its way to being accomplished. Private companies Space X and Virgin Galactic are preparing means for humans to much more easily access space. While we’re waiting for a ride on a Virgin Galactic flight, even today it is possible for the larger public to participate in how we approach space exploration.

Planetary Resources’ ARKYD telescope, backed by Peter Diamandis and funded on Kickstarter, allows individuals to access the telescope for research and ‘space selfies’. Made in Space, an SU company launched during the 2010 GSP, is slated to launch its 3D micro-gravity printer to the ISS this fall — and the public can have a say in the first objects manufactured in space.

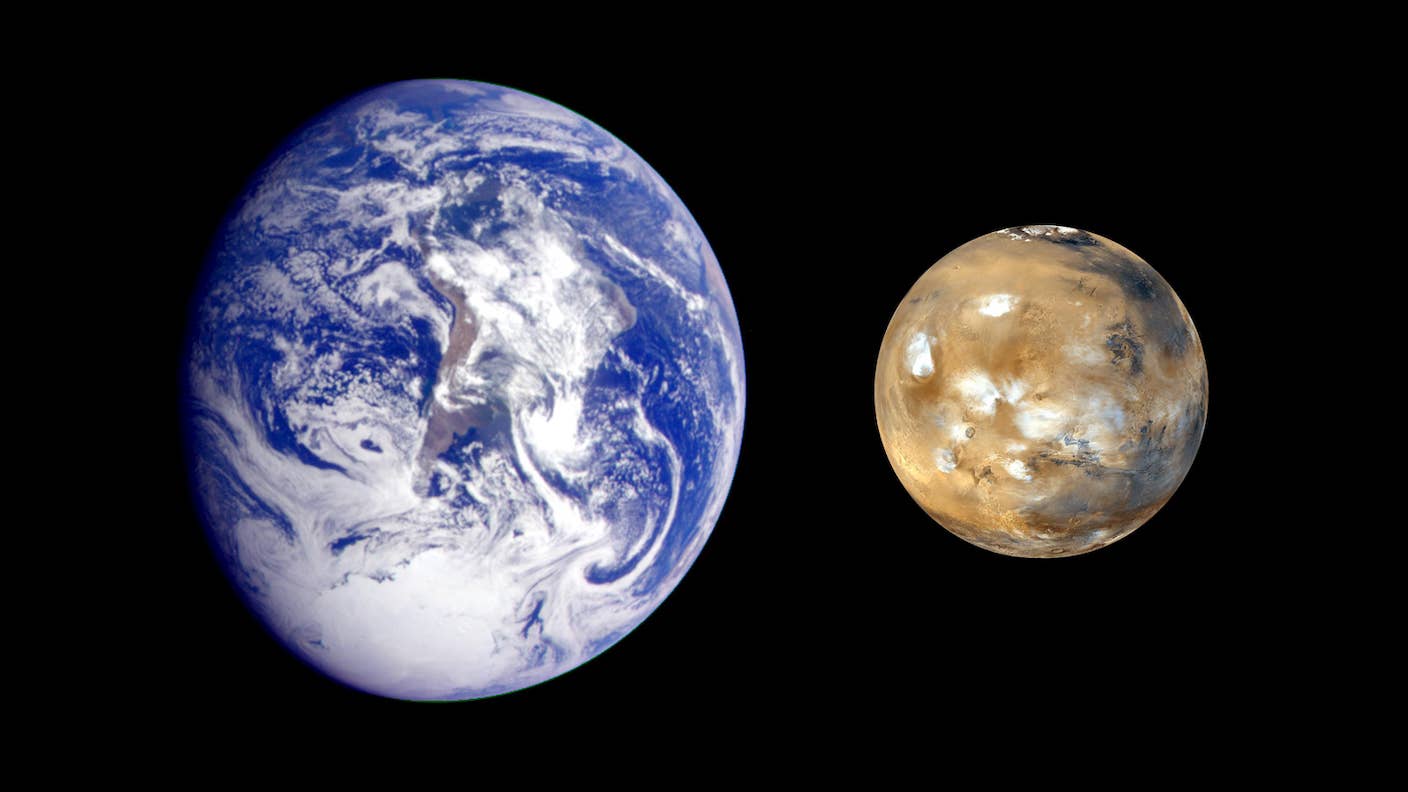

In recent years, so much of the focus on space has shifted to the science and economics of getting there — whether ‘there’ is the Moon, Mars, or beyond — and what we do once we get there, making it easy to overlook the innate human desire for exploration. With her emotional journey and inspirational message, Ansari sparked renewed curiosity about our place in the universe and an awe of how much is still left to learn.

Sveta writes about the intersection of biology and technology (and occasionally other things). She also enjoys long walks on the beach, being underwater and climbing rocks. You can follow her @svm118.

Related Articles

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

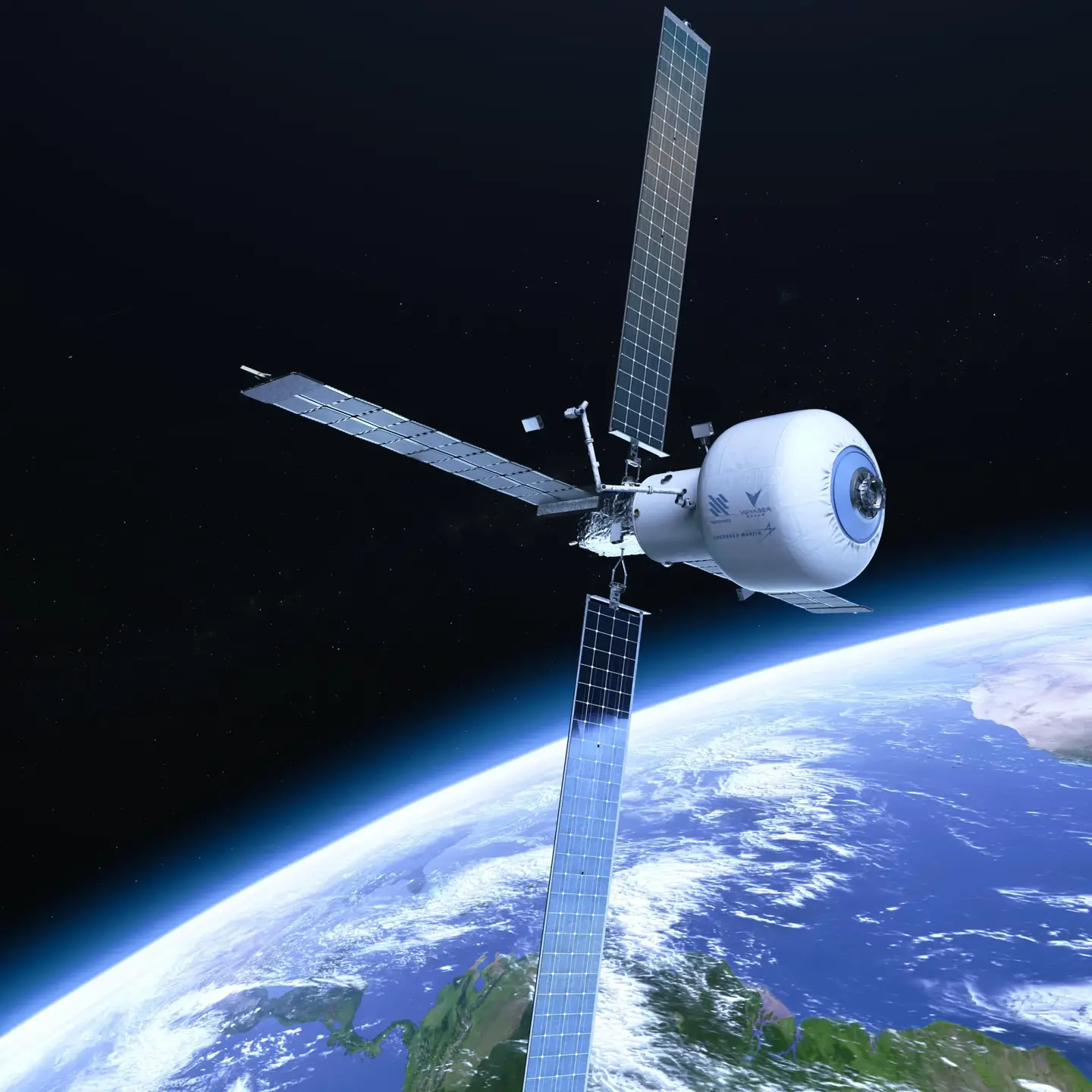

The Era of Private Space Stations Launches in 2026

What we’re reading