A Blood Test for Depression Moves Closer to Reality

Share

With the recent and highly publicized death of actor Robin Williams, depression is once again making national headlines. And for good reason. Usually, the conversation about depression turns to the search for effective treatments, which currently include cognitive behavioral therapy and drugs such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

However, an equally important issue is the timely and proper diagnosis of depression.

Currently, depression is diagnosed by a physical and psychological examination, but it mostly depends on self-reporting of subjective symptoms like depressed mood, lack of motivation, and changes in appetite and sleep patterns. Many people who might want to avoid a depression diagnosis for various reasons can fake their way through this self-reporting, making it likely that depression is actually under-diagnosed.

Therefore, an objective test could be an important development in properly diagnosing and treating depression. Scientists at Northwestern University may have developed such a diagnostic tool, one that requires no more than a simple test tube of blood.

A team of researchers, led by Dr. Eva Redei and Dr. David Mohr, found that blood levels of nine biomarkers—molecules found in the body and associated with particular conditions—were significantly different in depressed adults when compared to non-depressed adults.

The new study, published in the current issue of Translational Psychiatry, builds upon earlier work by Dr. Redei, who found the levels of 11 other biomarkers to be different in depressed versus non-depressed teenagers.

While this work is still in the early stages, it represents an important advancement in the correct diagnosis and treatment of major depressive disorder, which currently has a lifetime prevalence of 17% of the adult population in the US.

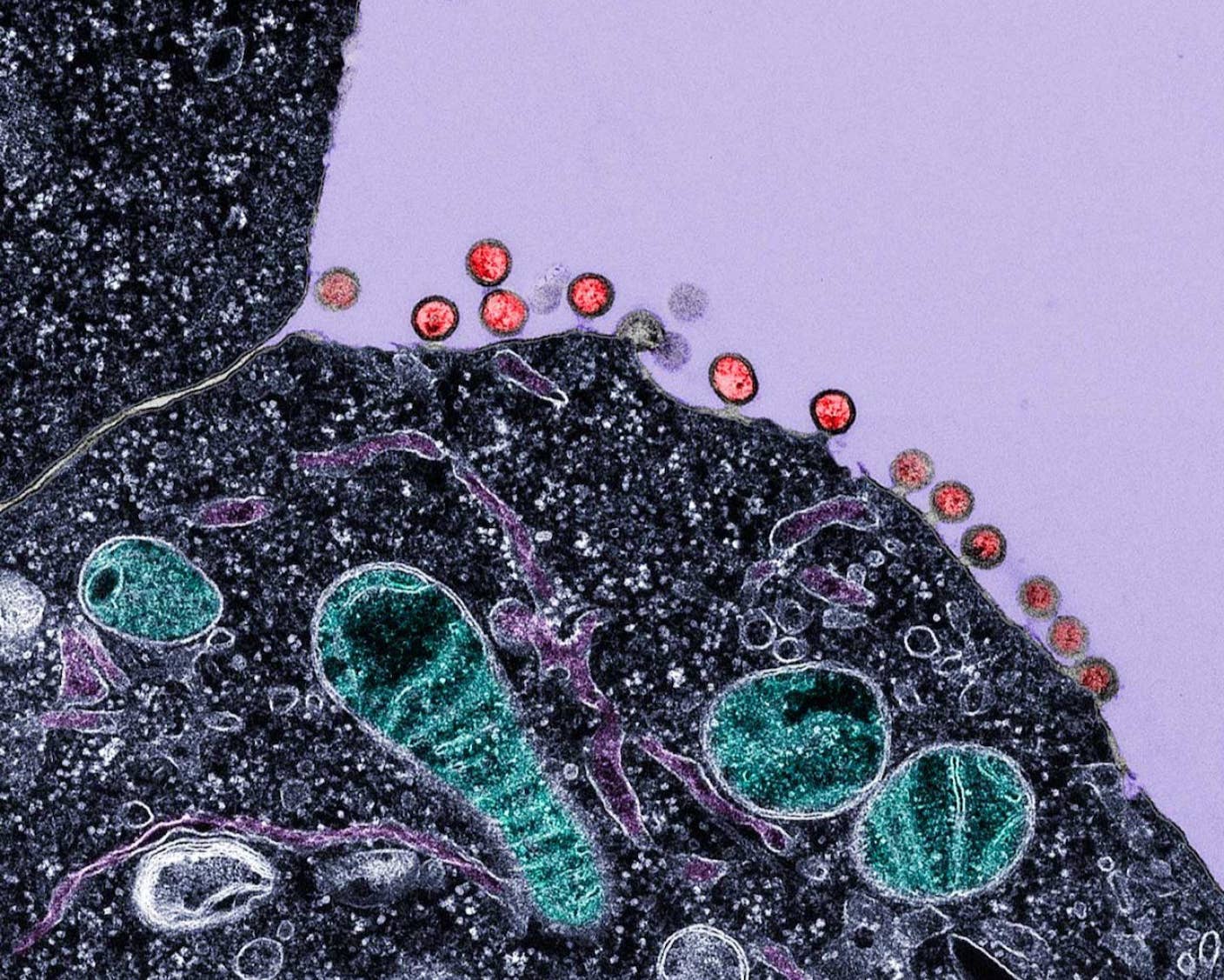

The new test looks at the levels of nine RNA markers in the patient’s blood. In case you forgot your molecular biology, RNA is the messenger molecule made using DNA as a template. In turn, cells then use RNA as a template to make proteins, which are the actual machines that do the work specified by the DNA.

The idea is that some genes can be overexpressed or underexpressed during depression and if those genes can be identified by looking at the RNA made from them, an objective way of identifying depression could be developed.

The researchers from Northwestern initially looked at the RNA levels of 26 genes in adolescents and young adults (ages 15-19). They found that 11 of them were significantly different in patients that had previously been diagnosed with depression versus those who were never diagnosed. They then tried to apply the same approach to adults and found significant differences in nine biomarkers.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Interestingly, the biomarkers that were found to differ in depressed versus non-depressed patients were actually different in young people and adults, implying that depression is genetically different when comparing different age groups.

Furthermore, the test was also able to identify differences between those who went through cognitive behavioral therapy and showed improvement versus those who showed no improvement after therapy. This kind of information can help predict the proper treatment regimen for patients, increasing their chance of going into remission.

While this work is still in the early stages and will take more studies to establish its accuracy and clinical usefulness, it represents an exciting development in diagnostics.

As medicine and genomics continue to change with the development of ever-increasingly powerful and cost-effective technology, we expect to get better at identifying and treating diseases before they take a significant toll.

These new blood tests have the potential to change our approach to diagnosing depression as well as selecting the proper treatment.

Sadly, many depression patients are resistant to the most common treatments so the need for new, more effective treatments is great. Finding differences in the expression of certain genes during depression could even lead to a clearer understanding of the disease, which in turn could lead to improved treatments down the road.

Depression is a thief that steals a productive and enjoyable life from far too many people around the world. Hopefully, this line of research will one day make it a thing of the past like smallpox.

Image Credit: Shutterstock.com

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

What we’re reading