Working Lab-Grown Human Muscles to Serve as ‘Clinical Trials in a Dish’

Share

A team of researchers out of Duke University recently announced they’ve grown human skeletal muscle in a dish. The muscle responds to electrical impulses, biochemical signals, and drugs just like muscle tissue in our bodies.

It’s hoped that in the future such lab-grown tissues might serve as a way to test new drugs and study diseases outside the human body without risking a patient’s health. They might also be used to provide more personalized therapies.

“We can take a biopsy from each patient, grow many new muscles to use as test samples and experiment to see which drugs would work best for each person,” said Nenad Bursac, associate professor of biomedical engineering at Duke and a lead researcher on the study.

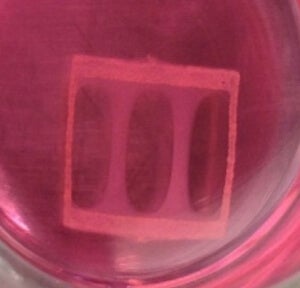

Bursac and Lauran Madden, a postdoctoral researcher in Bursac’s laboratory, grew the muscle tissue by first adding “myogenic precursors,” a kind of proto muscle cell, to a three-dimensional scaffolding and nutrient gel in a dish. As the cells matured, they lined up and formed working muscle fibers (shown here at the top of the page).

Bursac’s lab has been working on growing muscles in animals for some time. Last year they announced they had produced similarly impressive lab-grown muscles in mice. However, this is the first success the lab has had in functioning human muscle tissue.

“We have a lot of experience making bioartificial muscles from animal cells in the laboratory, and it still took us a year of adjusting variables like cell and gel density and optimizing the culture matrix and media to make this work with human muscle cells," said Madden.

In tests, Madden found the tissue contracted when given a shock and the pathways for nerve activation were present and in working order. She also found the tissue's responses to various drugs matched those observed in humans.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The scientists believe lab-grown tissue may serve as a proxy for medical tests.

Such methods may help researchers better pick drugs for clinical trials—many therapies that show promise in animal research do not bear fruit in human trials. An intermediate step may help weed out less effective therapies. Further, lab-grown tissue may offer a way to run tests on human tissue without putting patients at risk.

“The beauty of this work is that it can serve as a test bed for clinical trials in a dish,” said Bursac.

Bursac is working on a study to find out how accurate their tissue might be in such trials. The Duke team is also attempting to grow working muscles from induced pluripotent stem cells instead of biopsied cells.

"If we could grow working, testable muscles from induced pluripotent stem cells, we could take one skin or blood sample and never have to bother the patient again," said Bursac.

Image Credit: Duke University

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

More Space Junk Is Plummeting to Earth. Earthquake Sensors Can Track It by the Sonic Booms.

Researchers Break Open AI’s Black Box—and Use What They Find Inside to Control It

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 21)

What we’re reading