Why We Should Embrace — Not Fear — the Biohacker Uprising

Share

Dr. Steve Kurtz was making arrangements for his wife Hope’s funeral when the FBI burst in.

Kurtz, a professor of arts at the New York State University, was detained and interrogated for 22 hours as a bioterrorism suspect.

The previous day, Kurtz had dialed 911 in panic when Hope passed away in their home in Buffalo, NY. When the paramedics arrived, they were taken aback by dozens of petri dishes full of bacterial cultures casually strewn around the house. They thought I killed my wife with some sort of biochemical toxin, recalled Kurtz in an interview with the BBC.

It was all a tragic misunderstanding.

Kurtz, a trailblazing biohacker, was growing completely harmless bacteria for an art ensemble that, ironically, critiqued the UK-US bio-terrorism paranoia. Even though Kurtz licked the petri dishes right in front of the agents to prove his point, it still took four years for his charges to be acquitted.

Kurtz’s scare happened in May 2004, when biohackers were still a rare breed.

Since then, under the watchful eye of the FBI, the nascent DIYbio scene blossomed around the world. Dozens of thriving community labs in nearly 50 cities now act as hubs that support citizen scientists eager to hack biology — think engineering human night vision, real vegan cheese and glow-in-the-dark plants.

DIYbio’s growth spurt is, in part, thanks to powerful molecular biology tools becoming cheaper and simpler to use. Second-hand DNA amplifying machines are increasingly available over eBay, with some vintage models costing less than $100. Biohackers have even made an open-source version that, in true DIY fashion, allows amateur biologists to assemble the machines on their own.

Similar to sophisticated home chefs, amateur scientists no longer require specialized lab training. Want to transfer a gene from plant A to plant B? Simply purchase off-the-shelf, ready-made kits from an online supplier of your choice, follow the instructions, and within a few months (if you’re good) you’ve cooked up something entirely new to nature.

According to DIYbio pioneer Rob Carlson, what drives the movement is the belief that “biology is technology”: like computer software, DNA is fundamentally a form of code that can be manipulated to engineer biological traits and devices. At its core, much of the DIYbio movement is about exploring the creative potential of rewriting genes.

The DIYbio community’s intentions seem innocent. Yet some people are worried — for good reason — that amateur labs could become ample breeding grounds for next-generation superbugs or bio-terrorists.

The advent of CRISPR, arguably the most powerful DNA editing technique available to scientists today, further pushed biohackers into the spotlight. CRISPR, with the power to edit human embryos, grow human organs in pigs and even potentially bring back the woolly mammoth , is readily available to anyone willing to shell out a couple thousand bucks.

CRISPR’s prospect for mischief is not lost on the FBI’s bioterrorism protection team. Over the last few years, the FBI painstakingly fostered relationships with the biohacker community, urging members to scout out and report any suspicious activity.

There’s no doubt that the threat is there, but so far the fears seem premature, if not unwarranted.

Most biohackers are completely benign, says Dr. Todd Kuiken, a researcher that studies science policy at the Woodrow Wilson International Center think tank. Their main goals? Creating rainbow-colored bacteria or brewing funky beer.

There’s also a tendency to overestimate what typical biohackers can do. According to a survey of 359 biohackers by the Wilson Center, most of their activities are limited to extracting DNA from strawberries and other plants. Just 13% managed to synthesize a gene, and fewer than 3% succeeded in putting the gene into a cell. (Keeping it alive was another hurdle altogether.)

Molecular biology PhDs take years to complete for a reason: even with increasingly sophisticated tools, tinkering with biology in a specific, desirable way is incredibly difficult, in part due to the complexity of biological systems.

What’s more, specialized reagents such as enzymes are still very expensive (with no signs of prices dropping), molecular biology experiments are time-consuming and very finicky, and many community labs insist that their members only work with low-level organisms such as yeast or algae.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Human cells and pathogenic viruses are absolutely not on the menu, says Kuiken.

Another nightmare scenario surrounding CRISPR is that biohackers may inadvertently introduce genetic modifications that spread unnaturally fast throughout the natural ecosystem, with devastating consequences.

That’s far too difficult, laughed Dan Wright, an environmental lawyer and biohacker based in Los Angeles. Just knocking down one gene is currently very tough for the DIYbio space, and people just don’t stumble into making super-(evil)-organisms.

The challenge of manipulating living cells doesn’t sink in until you actually try it, Sue Luzzi, an accountant and DIYbio enthusiast told Singularity Hub. “Honestly it’s still hard getting access to CRISPR unless you have a connection to a university lab or something. I’m just happy that for the first time, we can kind of do what real scientists are doing. It’s super cool.”

And that, argues Dr. Ellen Jorgensen, is a great reason why we should embrace — not fear — biohackers. In December 2010, Jorgensen and colleagues opened Genspace, the world’s first community biotech lab, in Brooklyn, NY.

For the first time in decades, Americans perceive biology as deeply relevant to their lives, to the point that they want to contribute, wrote Jorgensen in Nature magazine. “Given the sad state of science literacy in this country, anyone excited about doing science should be encouraged by those with the knowledge and resources to help.”

Then there’s the tantalizing possibility that biohackers — untethered by traditional grad school training — may offer fresh viewpoints that could lead to new applications for existing technologies. It’s unfair to compare grassroots DIYbio to professional labs in terms of output, says Jorgensen, but the potential is there for them to make real advances in biomedicine some day.

“Even if the sole benefit is to enhance science literacy, that would be enough,” continued Jorgensen. Community labs are great ambassadors to make the latest biotech advances understandable and non-threatening to the general public.

Like hackers selling illegal services over the dark web, there might be vagabond biohackers working towards nefarious goals. But we shouldn’t let that threat impede garage biologists from realizing their creative ideas, just like we didn’t shut down garage computer enthusiasts from developing technology that permeated — and changed — the world.

“You don’t need a PhD to be a scientist,” says Robert Sabin, a pioneer who forged his path as a biohacker back in the 1980s.

“You need passion,” he emphasized. That’s what we got.

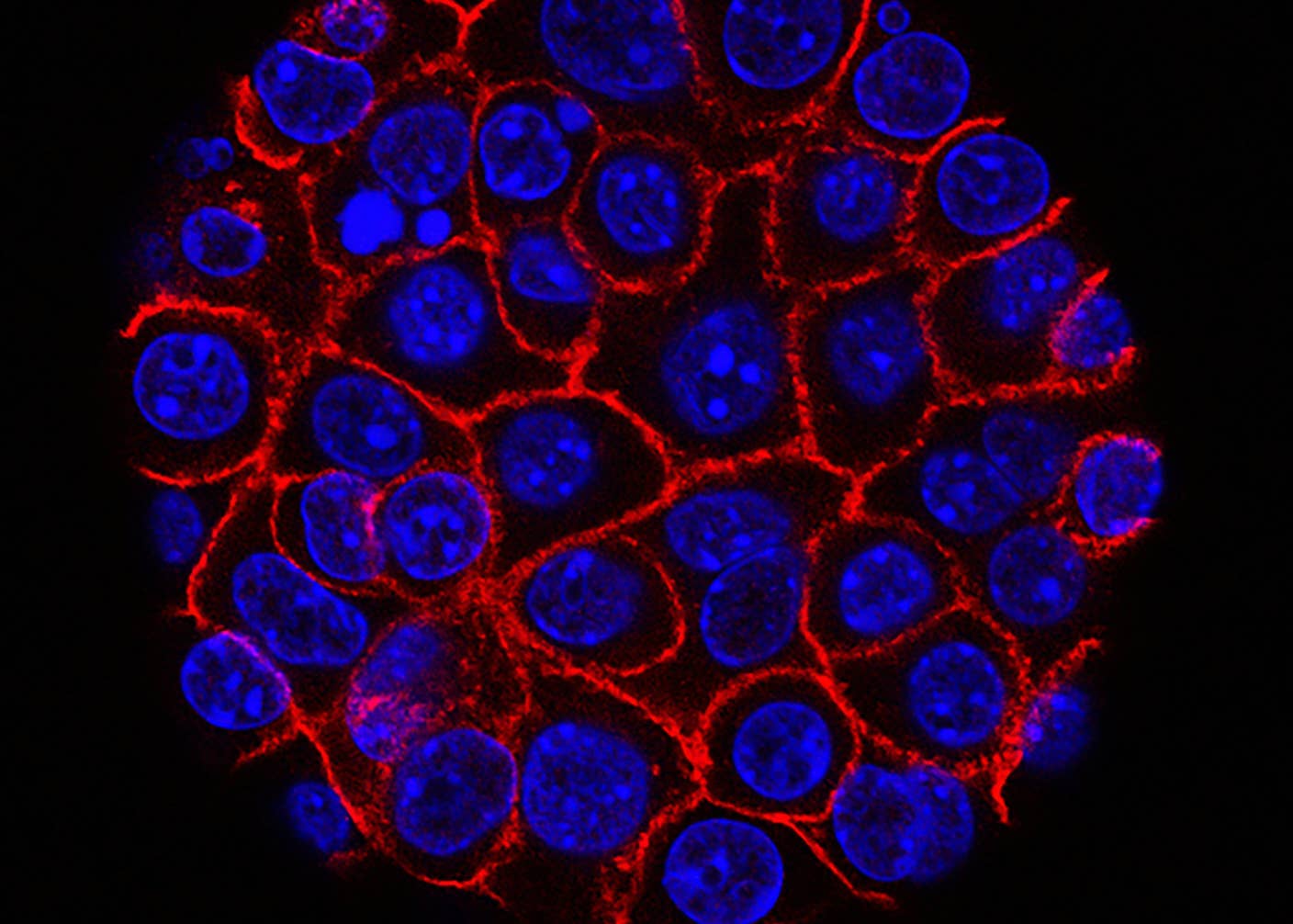

Image Credit: Shutterstock.com, .dh/Flickr (petri dishes, stickers, Ellen)

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

Souped-Up CRISPR Gene Editor Replicates and Spreads Like a Virus

What we’re reading