Smartphones to Bionic Body Parts: Our Tech Can (and Will) Be Used Against Us

Share

What might a crime headline look like in 2025? According to Marc Goodman, author of Future Crimes, it may read something like this:

“Man arrested for shooting his wife, acquitted on all charges after forensic evidence proves his bionic hand was hacked.”

(Goodman and NPR’s Science Friday conducted a Twitter poll on the question—check out more headlines here.)

Most crimes through history have been committed in person (and by human hands), but with the Internet of Things, UAVs, and artificially intelligent assistants, crimes like an AI assisted murder or a man framed by his hacked bionic hand may become plausible accounts of misconduct in the not-so-distant future.

Though some of that may still be a little ways off, the new face of crime is already here—cybercrime, for example, is now being committed on previously unthinkable scales. As our lives become increasingly digitized, one question rises top-of-mind: How do we protect our digital lives from being hacked?

Future Crimes: Everything Is Connected, Everyone Is Vulnerable and What We Can Do About It by Marc Goodman

Fortunately, Goodman—a former LAPD officer with experience working with the US Secret Service, FBI, Interpol and police departments in over 70 countries—wrote Future Crimes as a public wake up call, and it’s gained wide attention.

Future Crimes is a New York Times and Wall Street Journal best seller and was recently named Amazon’s best business book of 2015 and one of The Washington Post’s Top 10 books overall in any category for 2015.

Earlier this year, we sat down with Goodman—who is policy, law, and ethics chair at Singularity University—for an in-depth two-part interview before the book was released.

With mounting attention since publication, we knew we needed to revisit the book with Goodman to find out more about why he thinks it struck a chord and what the implications are for online security of citizens, governments, and beyond.

After sitting down with Goodman for round two, here’s a firsthand account of his views on which technology is most susceptible to cybercrime, what individual privacy means in 2015, and steps we can take to better secure our digital lives.

Why is 2015 the year of future crime? What is happening in the minds of business leaders that this topic is in such high demand?

The cyberthreat has finally come into the public’s mindset.

After various reports on massive data breaches, both the general public and the business world understand that information leaks. As we produce exponentially more and more data, we can expect a concomitant growth in data leaks.

Of course, “future crimes” are not just about hacked credit cards and identity theft.

That is the primary point in Future Crimes—all of our technology, for all the good it portends, can be used against us. Robotics, artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, the Internet of Things, and even virtual reality can be exploited by criminals, terrorists, hacktivists and rogue governments.

In your opinion, who is ultimately most responsible for upholding digital security and privacy—users, companies, governments, or some other organization?

Option D—all of the above.

There is no single individual or sector that can ensure a more secure society. That responsibility defaults to us all. That said, on the security front, we have to take an epidemiological approach to this problem and understand where technological risk originates. Today, this can be answered quite simply: poor computer code.

All hacking, worms, viruses and Trojans take advantage of errors in coding, exploits made possible due to insecure code. Fix that and the cyber-risks go away. Of course, fixing that and creating “perfect” computer code is nigh impossible. What is possible, is vastly improving our dedication to secure coding—that is, ensuring the quality of our code is much better than it is today.

With some programs like Microsoft Office having more than 50-100 million lines of code—this is no easy feat. That said, secure coding should be taught in all computer science programs. Technologists and scientists must understand that their coding actions have consequences—a concept that is barely a consideration today, where the average start-up’s mantra is “just ship it.” Get the code out the door and we’ll fix it later in update after update.

That may have worked when dealing with spreadsheets or browsers, but it surely does not work with pacemakers, automobiles, and electrical grids.

Governments must also significantly up their game in the realm of cybersecurity.

Sadly, heretofore, they seem incapable of doing so. We expect governments to protect us from threats foreign and domestic. Sadly, in the age of exponentially growing transnational cyberattacks, the government has done little to protect its citizenry. This isn’t a huge surprise, given the government’s inability to protect itself. We saw this with the theft of more than 20 million background investigation files during the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) data breach earlier this year.

The question is, if the government can’t protect itself, how can it protect you?

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

But government does have a role to play. We pay too much in taxes for the government to abdicate its role in protecting the citizenry of a nation. They must significantly improve their game, and this will require considerable help from the private sector and from academia to get there. That’s why I’ve called for a “Manhattan Project for Cybersecurity.”

Beyond that, individuals must learn how to protect themselves in cyberspace.

We know how to protect ourselves in the physical world. We lock our doors when we go to work, and we don’t leave our keys in our cars when we go shopping at the mall. Now, we need to learn how to do the same in the virtual space, and a mass education campaign would help close the gap.

As it turns out, simple steps related to our passwords and encryption and updating our software can have a huge impact on our personal cyber security—reducing risks by nearly 85% according to a study by the Australian Ministry of Defence.

What technology or device that most people use every day is most susceptible to cybercrime?

In 2015 and 2016, the answer to that is easy. It’s the mobile phone.

Mobile phone security stinks—particularly on Android devices, which are the subject of more than 95% of all smartphone hacks. As we do more and more with these portable computers—banking, health care, online purchases—we will see the risks rise even further.

It is trivial to infect an Android mobile phone with malware. In 2015, we saw the Stagefright bug—an exploit that opened the door for hackers—take over and infect nearly a billion android devices around the world with a simple infected SMS text message. Once infected, hackers could track a user’s location, remotely activate the phone’s microphone and commandeer its video camera. We have a long way to go in terms of securing mobile devices.

How do you personally define individual privacy in 2015? How do you think it will be defined ten years from now? Should we even have a reasonable expectation of digital privacy anymore?

I think privacy has always been about personal control and empowerment—having the right to define for ourselves what information we want to share with the world and under what circumstances.

Clearly, our privacy is under assault, and living in a digital world is only accelerating that trend.

In the age of big data, ubiquitous cameras, and a trillion sensor economy, it will be nearly impossible to keep elements of our lives private, intimate, and to ourselves.

That said, I do believe privacy is a fundamental human right and is enshrined as such by the United Nations, the European Union, and many governments around the world. While it’s easy to believe that a total lack of privacy is inevitable and there is nothing we can do to prevent it, we clearly should “not go gentle into that good night” but rather “rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

Those that say our loss of privacy is unavoidable tend to be those with something to gain by abrogating our privacy—for example Internet companies who profit heavily from the aggregation of our personal data. Today is a unique moment in human history, and the decisions we make today from a public policy, legal, and ethical perspective will affect generations to come and the future of privacy itself.

It’s time to draw a line in the sand.

Image Credit: Shutterstock

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Alison tells the stories of purpose-driven leaders and is fascinated by various intersections of technology and society. When not keeping a finger on the pulse of all things Singularity University, you'll likely find Alison in the woods sipping coffee and reading philosophy (new book recommendations are welcome).

Related Articles

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

These Brain Implants Are Smaller Than Cells and Can Be Injected Into Veins

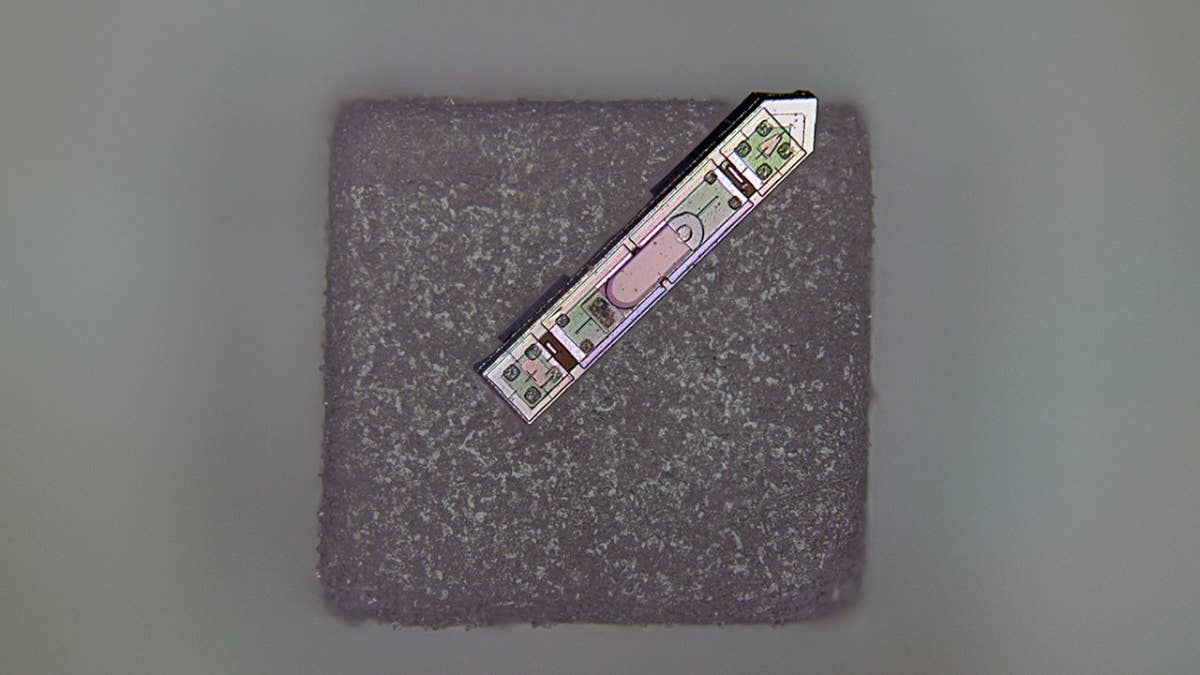

This Wireless Brain Implant Is Smaller Than a Grain of Salt

What we’re reading