The World Depends on Technology No One Understands

Share

“We are in a new era, one in which we are building systems that can’t be grasped in their totality or held in the mind of a single person.” – Samuel Arbesman

As a teenage nobody, George Hotz earned notoriety for being the first hacker to unlock Apple’s iPhone — much to the annoyance of AT&T, who had exclusive-ish networking rights at the time. Several years later, he became the focus of a Sony lawsuit for releasing hacked Playstation 3 software to the world. And last December, he discussed his latest project with Bloomberg’s Ashlee Vance — a patched together home-made driverless car.

When asked what compels him to crack open these complicated technologies Hotz said, “I want power. Not power over people, but power over nature and the destiny of technology. I just want to know how it all works [emphasis added].”

If knowing how it all works is Hotz’s driving purpose, he has ironically chosen to work with one of the very technologies launching us, unquestionably, into an era of unknowability. In the case of machine learning AIs, like those used in driverless cars, no one person — not even the experts who design them — understands exactly how they function.

Welcome to the age of entanglement.

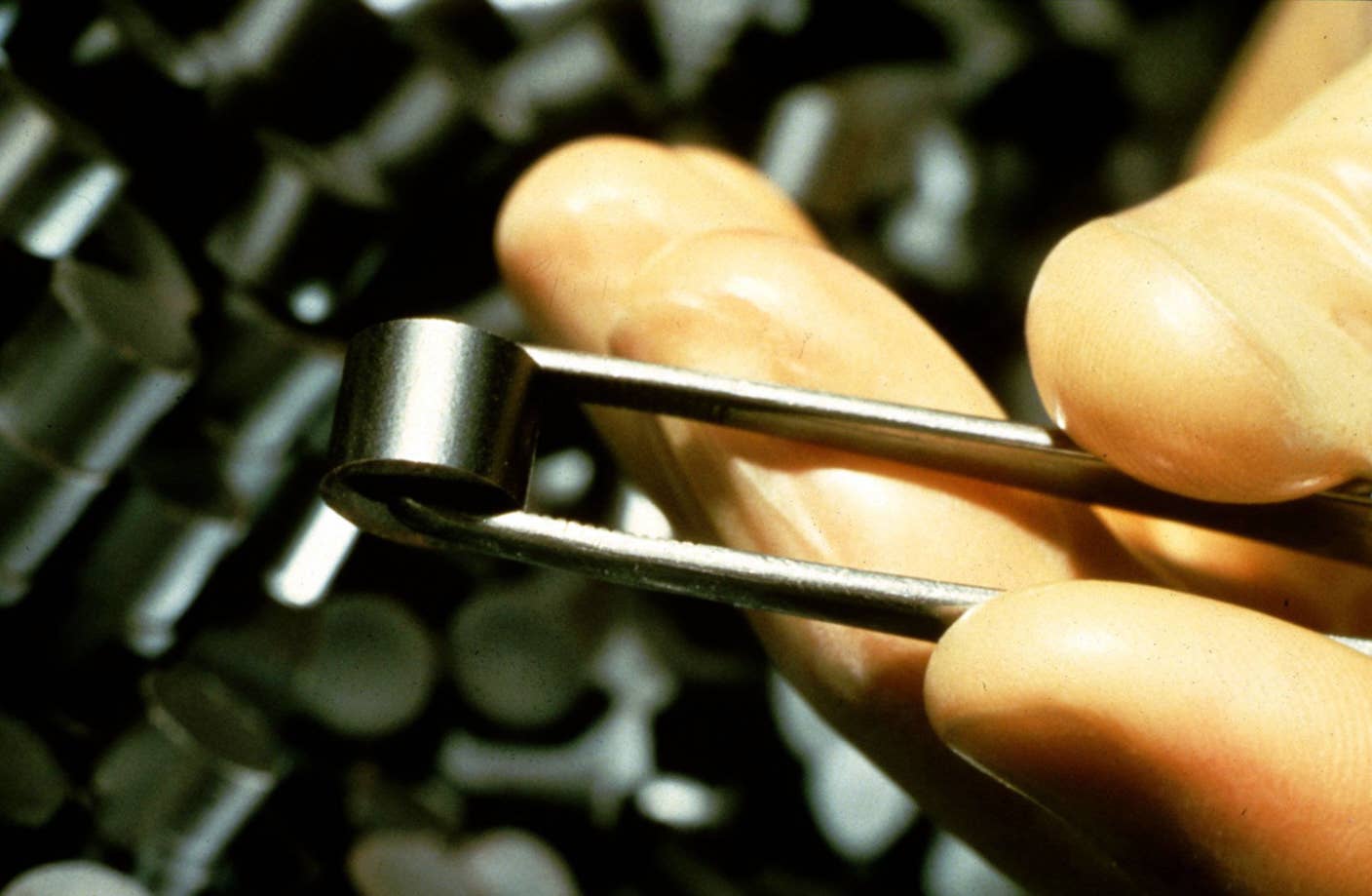

Image credit: Rob Bulmahn/FlickrCC

This week Samuel Arbesman, a complexity scientist and writer, will publish Overcomplicated: Technology at the Limits of Comprehension. It’s a well-developed guide for dealing with technologies that elude our full understanding. In his book, Arbesman writes we’re entering the entanglement age, a phrase coined by Danny Hillis, “in which we are building systems that can’t be grasped in their totality or held in the mind of a single person.” In the case of driverless cars, machine learning systems build their own algorithms to teach themselves — and in the process become too complex to reverse engineer.

And it’s not just software that’s become unknowable to individual experts, says Arbesman.

Machines like particle accelerators and Boeing airplanes have millions of individual parts and miles of internal wiring. Even a technology like the U.S. Constitution, which began as an elegantly simple operating system, has grown to include a collection of federal laws “22 million words long with 80,000 connections between one section and another.”

In the face of increasing complexity, experts are ever more likely to be taken by surprise when systems behave in unpredictable and unexpected ways.

Analysts picking apart the 2010 ‘flash crash’ — when increasingly algorithm-fueled financial markets inexplicably nosedived only to recover minutes later — likened examining what happened to studying crop circles. (And we’re still not fully sure what caused it). Naturally, this confusion will give rise to technological unease. When a driverless car is involved in a fatal collision, we’re unlikely to uncover exactly what went wrong.

Take, for example, the case of July 8th, 2015, the day United Airlines flights were fully grounded while the New York Stock Exchange and the Wall Street Journal’s website were brought down. The culprit? “A lot of buggy software that no one fully grasped,” suggests Arbesman.

So how do we move forward?

His book makes a compelling case that we’ll need a natural science approach. Consider, for a moment, how we deal with weather. “While we can’t actually control the weather or understand it in all its nonlinear details, we can predict it reasonably well, adapt to it, and even prepare for it.” Arbesman suggests we may soon model computer glitches the same way.

“We’ll need interpreters of what’s going on in these systems, a bit like TV meteorologists,” he writes.

In the entanglement age, our relationship to technology has evolved to be like our relationship to nature. We’re returning to the jungle — only this time we've constructed it ourselves.

While some may be gripped by fear in the face of increasing uncertainty, others may greet the new landscape with a deep-felt sense of awe.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

As I considered the world Arbesman sketches, where synchronized systems operate outside of both our comprehension and control, I was overcome with the same feeling that glued me to my seat following the release of the BBC’s Planet Earth series. Peering into the impossibly complex design of Earth’s natural systems — in high definition no less — left me hypnotized for days.

Paris from space. Image credit: NASA

Perhaps someday an equivalent documentary series could be made about the technologies running our future world. Elegant delivery systems autonomously hum through our cities while automated financial markets transact in the background and businesses conduct commerce on their own. All the while, the true mechanics of this civilization would remain hidden in mystery.

This is speculative, of course, but as Arbesman cites from a 2013 paper in Nature, in the financial world, there is already a “complete machine ecology beyond human response time.”

We may stand back in amazement, simultaneously feeling pride for what we’ve built and perplexed by how things run. I’m reminded of a moment at the end of a recent Long Now seminar when Kevin Kelly is asked if poets and mystics will write “odes” to our machine world.

Arbesman offers words of caution to those overwhelmed by either fear or awe.

When we spoke about this by phone earlier this year, he shared that “both cut off our ability to question our technologies. So, in between the two is humility.” In the book, he elaborates on this idea by writing that “humility simply means accepting that scientific triumphalism is misplaced: we can never achieve complete or perfect understanding.”

As we embed more systems into our technological eagle’s nest, civilization will rest on frameworks we no longer fully understand. Arbesman’s book does, however, leave readers feeling upbeat that we will learn to thrive in this era.

Our enlightenment age of science, driven by an urge to control the material world, is only a few centuries old yet now appears destined to become a blip in human history. Where we once held the promise that we could bring order to the chaos and unpredictability surrounding our lives, we’re now moving into the entanglement age where the notion of full control is coming to a swift and final close.

We must now, as Arbesman says, walk humbly with our technology.

Banner image courtesy of Shutterstock.

Aaron Frank is a researcher, writer, and consultant who has spent over a decade in Silicon Valley, where he most recently served as principal faculty at Singularity University. Over the past ten years he has built, deployed, researched, and written about technologies relating to augmented and virtual reality and virtual environments. As a writer, his articles have appeared in Vice, Wired UK, Forbes, and VentureBeat. He routinely advises companies, startups, and government organizations with clients including Ernst & Young, Sony, Honeywell, and many others. He is based in San Francisco, California.

Related Articles

AI Now Beats the Average Human in Tests of Creativity

Meta Will Buy Startup’s Nuclear Fuel in Unusual Deal to Power AI Data Centers

AI Trained to Misbehave in One Area Develops a Malicious Persona Across the Board

What we’re reading