Living Eye Implant Uses Lab-Grown Cells to Restore Sight

Share

Our eyes are one of our most complex body parts, made up of numerous delicate cell structures that work together seamlessly to allow us to see. Conditions like far-sightedness, glaucoma, and cataracts are widespread, and it’s no wonder given the fragile nature of the eye’s many components.

In the worst-case scenario, optical cells malfunction to the point of blindness. But a group of scientists at the University of Melbourne in Australia recently took a critical step towards alleviating and even curing a common vision problem. Added to groundbreaking work in other areas, blindness could become an affliction of the past.

How our eyes work

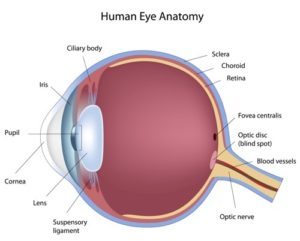

How does light go from entering our eyes to projecting a recognizable image in our brains?

At the front of the eye is the cornea, a saran-wrap-like transparent layer of cells that filters and focuses incoming light. Behind the cornea is the iris, commonly brown or blue in color, with the pupil at its center. The pupil expands or contracts to regulate the amount of light that hits the eye’s internal lens. After passing through the lens, light travels through the eyeball’s vitreous body to reach the retina, a layer of cells that sends electric signals to the brain via the optic nerve. The brain then translates these signals into the images we see.

Along with cataracts and glaucoma, the World Health Organization lists corneal opacities as one of the leading causes of blindness in both developed and developing countries. The cornea has to maintain a constant thickness and moisture level to stay transparent. This is accomplished by corneal endothelial cells, located on the cornea’s inner surface. Endothelial cells maintain the cornea by flushing excess water out. If these cells stop functioning due to injury, illness, or aging, liquid buildup on the cornea starts to impair vision, leading to blindness if left untreated.

Since endothelial cells can’t regenerate or repair themselves, the only way to restore the cornea’s function used to be through a cornea transplant, also called a keratoplasty. But a worldwide shortage of donor corneas, damage to corneal cells during the transplant process, and risk of the recipient’s immune system rejecting the donor cornea make transplants a less than optimal solution.

Corneal cells grown in a lab

In a groundbreaking new method, scientists were able to take samples of corneal cells from subjects’ eyes and cultivate the cells in a lab. Cells were regenerated and multiplied on a synthetic hydrogel film, then the film was implanted back into subjects’ eyes.

At 50 micrometers, the film is similar in thickness to the average contact lens. Its lab-grown corneal cells get to work restoring the balance of liquid below the cornea, and within two months the synthetic film biodegrades, leaving the healthy cells behind to continue maintaining the cornea’s moisture balance.

It’s important to note this procedure hasn’t been tested on humans, but it did restore vision in animals without causing adverse immune reactions. Clinical trials in humans are on track to start as soon as 2017, with life-changing implications for people suffering from corneal opacity.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

And it’s not only people with this condition who can place new hope in technology; artificial solutions for different vision complications are advancing as quickly as biological solutions.

Bionic eyes

In 2013, the FDA approved the first bionic eye implant to treat retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited eye disease that causes the retina’s photoreceptor cells to degenerate. Users of the technology wear a pair of glasses equipped with a tiny video camera. Data goes from the camera to a video processing unit to a group of electrodes implanted on the retina. The electrodes transform the data into electrical impulses that stimulate the retina to produce images.

A procedure to counteract age-related macular degeneration, the leading cause of blindness in people over 55, removes the eye's natural lens and replaces it with a pea-sized telescopic lens that magnifies objects and projects images onto the retina’s remaining healthy area (portions of the retina cease to function normally in people with this condition).

These technologies have already helped restore sight to thousands of people, but they have a ways to go before reaching the biological equivalent of the human eye’s perfect vision. Patients with retinal or lens implants have reported issues like poor resolution, difficulty detecting high-speed motion, and a limited field of view. The retinal chip cannot yet display color, capturing images only in black and white.

With continued advances in both biological vision treatments like corneal cell regrowth and artificial solutions like the bionic eye, blindness could one day be an affliction of the past.

Image credit: Shutterstock

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

Souped-Up CRISPR Gene Editor Replicates and Spreads Like a Virus

Your Genes Determine How Long You’ll Live Far More Than Previously Thought

Google DeepMind AI Decodes the Genome a Million ‘Letters’ at a Time

What we’re reading