Pulling Water, Fuel, and Power From Thin Air Is Getting Practical

Share

Pulling things from thin air is generally considered a magic trick. But several recent research papers suggest we could soon be extracting valuable resources like water, fuel, and power from the atmosphere.

Startup Carbon Engineering published a new technique for turning atmospheric CO2 into fuel last week that is starting to make the approach seem economically viable. And just a day later, a pair of papers outlined new ways to pull water from the air, one by harvesting fog more effectively and another that can extract moisture even in the driest deserts.

The idea of pulling gases from the air is not new; air separation plants have long been used to extract abundant nitrogen and oxygen for use in heavy industry. But the low proportion of CO2 in the atmosphere (roughly 0.038 percent) means these approaches can’t extract it in a viable way.

Carbon capture and storage technology is used to extract the gas from the exhausts of power stations and other CO2-producing plants, and in April I reported on an analysis from the University of Toronto predicting that within five to ten years, it could be economically viable to convert it into fuels and chemicals.

But in a paper in the journal Joule, Carbon Engineering and researchers from Harvard University estimated they can pull CO2 directly from the atmosphere for as little as $94 per metric ton and no more than $232, which works out to between $1 and $2.50 to remove the carbon dioxide a modern car would produce burning through a gallon of gasoline.

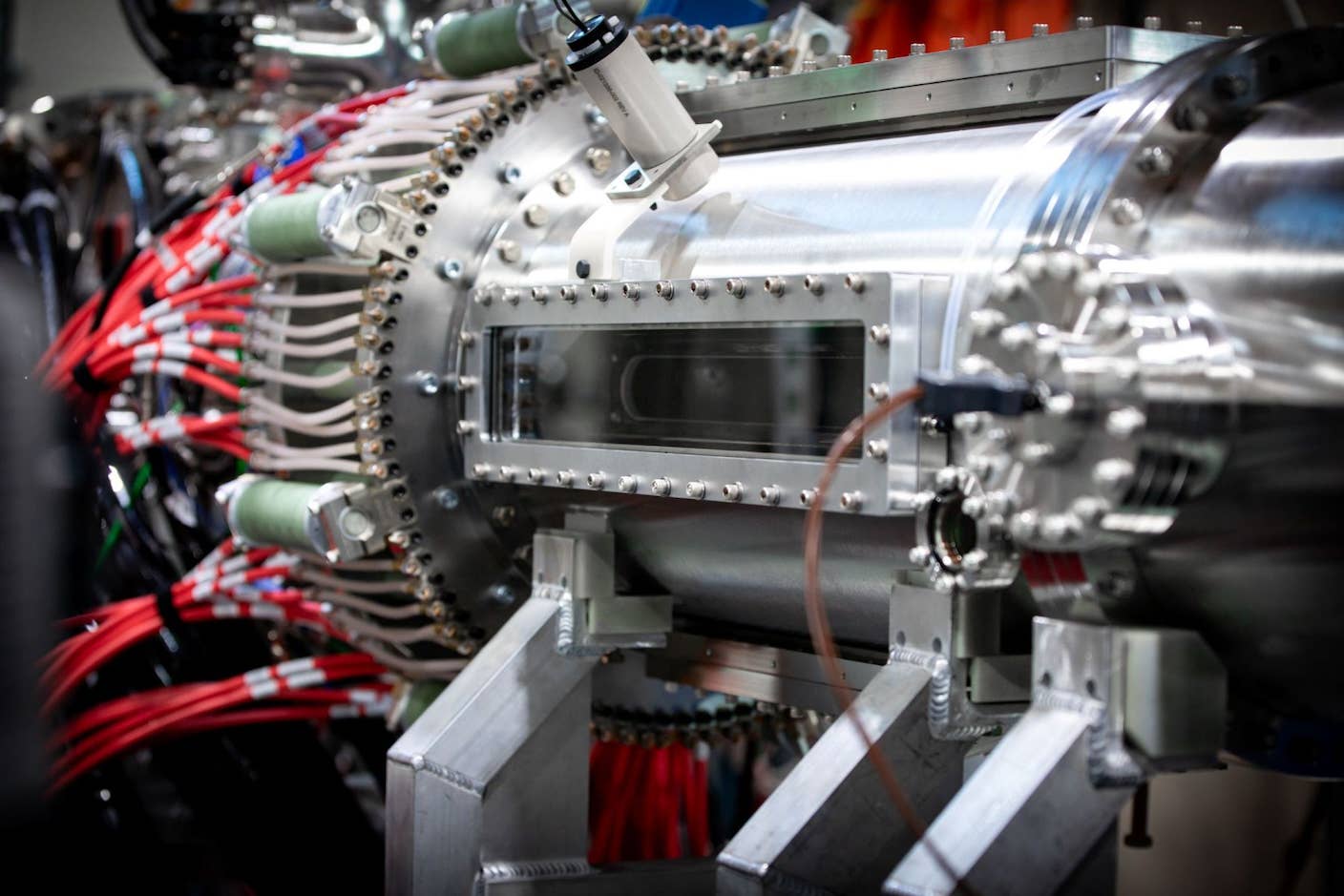

Their approach involves using giant fans to draw air into what look like cooling towers whose interiors are designed to allow the air to come into contact with a liquid solution that traps the CO2. Using similar chemical processes to those used in paper mills, the CO2 is extracted then combined with hydrogen to create carbon-neutral fuels. The company is already testing the approach at a pilot plant in British Columbia.

Pulling water from the air is an approach with longer pedigree—people have been harvesting condensation for millennia—but doing it at scale is much harder. Finding solutions could have a massive impact on water scarcity, though, because some of the areas with the biggest water scarcity problems also have high humidity, like the coastal areas of the Middle East.

Mesh nets used to catch droplets of water called fog harvesters are a low-tech way of collecting water from the atmosphere that’s already widely used. But in a paper in Science Advances, engineers from MIT described how they made this process far more efficient by using electrodes to electrically charge incoming water droplets so they were attracted to a metal mesh.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The engineers have created a startup called Infinite Cooling off the back of the research that plans to use the devices to reclaim the huge amounts of water that billow out of cooling towers at power plants.

The same issue of Science Advances also included another paper from UC Berkeley researchers, who exploited super-absorbent materials called metal-organic framework (MOF) to extract water from the air in one of the driest environments in the world, the Arizona desert. The material sucks up water at night, when humidity is comparatively high, and the heat of the sun is then used to drive it back off during the day so it can be collected.

These techniques are already moving from academia to the real world. The Water Abundance XPRIZE was set up to challenge teams to create technology that could extract 2,000 liters of water a day from the air for no more than 2 cents (1.4 pence) per liter. Earlier this year five finalists were selected to compete for the top prize, with testing due to start next month.

Thin air can even be a direct source of energy. Researchers from the University of Washington have demonstrated it’s possible to harvest useful amounts of electricity from the TV, radio, cell-phone, and WiFi signals constantly bathing the modern world.

The amounts are very small, but by combining this energy harvesting with techniques to reflect WiFi signals in a way that encodes new information in them called back-scattering, the approach could create wireless gadgets that never need to have their batteries replaced. Startup Jeeva Wireless is already commercializing the idea, and its battery-free prototypes have beamed data as far as 100 feet.

So next time someone claims to be able to pull something from thin air, it may pay to be less skeptical. Maybe they’re actually pitching you a novel idea for a startup!

Image Credit: Everyonephoto Studio / Shutterstock.com

Related Articles

Hugging Face Says AI Models With Reasoning Use 30x More Energy on Average

Startup Zap Energy Just Set a Fusion Power Record With Its Latest Reactor

Scientists Say New Air Filter Transforms Any Building Into a Carbon-Capture Machine

What we’re reading