The Private Space Industry Is Breaking Out of Earth’s Orbit

Share

Hopes for the first ever privately-funded moon landing were dashed last Thursday after the Israeli spacecraft Beresheet crashed on its final descent. But despite the disappointment, the episode signals the start of a new phase in private space exploration as it breaks out of Earth’s orbit.

The Israeli effort was led by non-profit SpaceIL, which formed to compete in the $30 million Google Lunar XPRIZE designed to spur private exploration of the moon. After several extensions the competition was finally shuttered without a winner last January, but SpaceIL continued with their mission regardless.

Everything was going smoothly until the main engine designed to slow the vehicle’s descent for a soft landing failed at the last minute. Communication was lost and the lander is assumed to have crashed, but it has nonetheless crossed a major milestone by becoming the first private spacecraft to reach the moon’s surface—even if not in one piece.

And it’s certainly not going to be the last. Former XPRIZE contestants ispace, Astrobotic, and PTScientists all have credible plans to visit the moon in the near future. Their long-term goals include setting up a regular lunar delivery service and mining for ice, which could provide water, oxygen, or hydrogen fuel for other missions heading deeper into the solar system.

This marks a significant shift for the private space industry, which has so far been largely focused on satellites, and more recently on lifting those satellites into orbit with the advent of companies like SpaceX.

The collapse of the Lunar XPRIZE last year was seen by many as a signal of how impractical the vision of commercializing space exploration was, and how far away we were from the sci-fi vision of corporations colonizing space seen in movies like Alien and Total Recall.

But just a year later, Beresheet seems to have proved many of the doubters wrong. The mission was funded by a non-profit, but the fact that it cost a fraction of most government-led projects at just $100 million might make people reconsider some of their assumptions about the economic viability of commercial exploration.

Admittedly, Beresheet’s ultimate failure highlights the risk of opting for faster, cheaper missions. But that hasn’t put off NASA, which recently chose nine companies to compete for $2 billion worth of contracts to send small experiments to the moon over the next decade.

A series of recent asteroid missions could also potentially jump start a faltering asteroid mining industry. Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft has been firing various projectiles at the asteroid Ryugu to try to identify what’s beneath its surface, and plans to return samples to Earth by the end of next year.

The US’ first mission to collect and return an asteroid sample to Earth, OSIRIS-REx, is also currently surveying the surface of its target, Bennu, with the aim of returning a 60-gram (2.1 oz) chunk to Earth at the end of 2023.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The success of these missions could provide a shot in the arm for an industry that has struggled since President Trump’s decision to cancel NASA’s plan to bring an asteroid close to Earth and send astronauts up to collect samples. Deep Space Industries and Planetary Resources were two of the leading pioneers in this space, but have both been bought out after falling on hard times.

Part of the problem for most commercial space operations looking beyond Earth’s orbit is that they are highly reliant on governments. Most companies are looking to either deliver experiments or provide resources like fuel and water for more ambitious exploration, but the only customers for those services right now are national space agencies.

That may be starting to change, though. SpaceX, which got rich from the first commercial space boom, is now looking forward to more ambitious projects in deep space. While its plans to colonize Mars probably need to be taken with a pinch of salt right now, the company is rapidly building the infrastructure to make these kinds of missions a possibility.

Just last week, the company completed its first commercial launch of its Falcon Heavy heavy-lift rocket and successfully landed all three boosters to be reused on future missions.

What the commercial deep space industry needs now is an ecosystem that can start to make it self-sustaining. The breakthroughs made by Beresheet and the Falcon Heavy last week are the first tantalizing signs that this might be starting to appear.

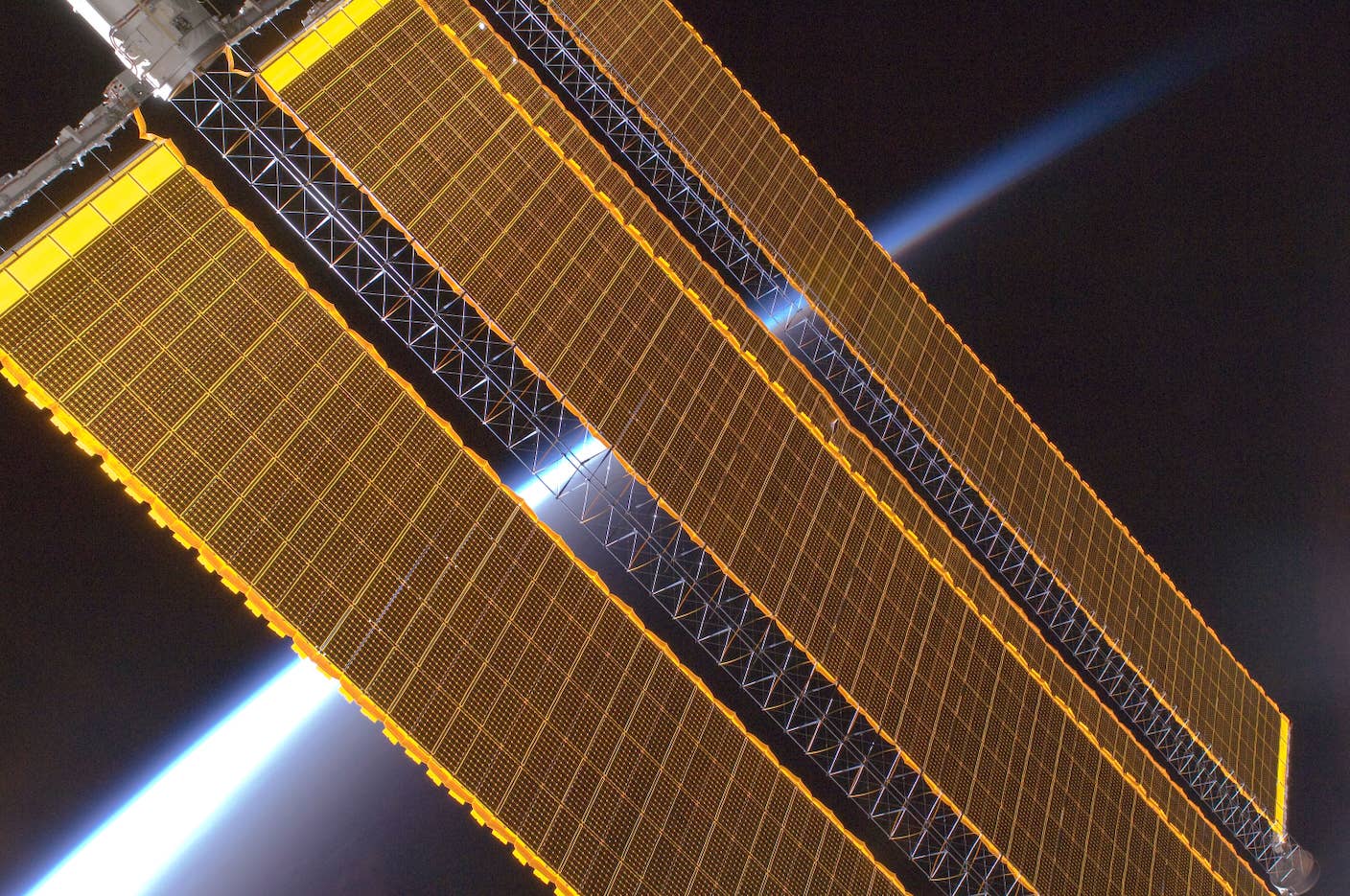

Image Credit: SpaceX / Planetary Society / Public Domain.

Related Articles

Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

Scientists Say We Need a Circular Space Economy to Avoid Trashing Orbit

New Images Reveal the Milky Way’s Stunning Galactic Plane in More Detail Than Ever Before

What we’re reading