The World’s Oldest Story? Astronomers Say Global Myths About ‘Seven Sisters’ Stars May Reach Back 100,000 Years

Share

In the northern sky in December is a beautiful cluster of stars known as the Pleiades, or the “seven sisters.” Look carefully and you will probably count six stars. So why do we say there are seven of them?

Many cultures around the world refer to the Pleiades as “seven sisters,” and also tell quite similar stories about them. After studying the motion of the stars very closely, we believe these stories may date back 100,000 years to a time when the constellation looked quite different.

The Sisters and the Hunter

In Greek mythology, the Pleiades were the seven daughters of the Titan Atlas. He was forced to hold up the sky for eternity, and was therefore unable to protect his daughters. To save the sisters from being raped by the hunter Orion, Zeus transformed them into stars. But the story says one sister fell in love with a mortal and went into hiding, which is why we only see six stars.

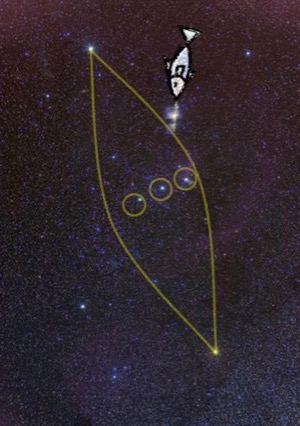

An Australian Aboriginal interpretation of the constellation of Orion from the Yolngu people of Northern Australia. The three stars of Orion’s belt are three young men who went fishing in a canoe, and caught a forbidden king-fish, represented by the Orion Nebula. Drawing by Ray Norris based on Yolngu oral and written accounts.

A similar story is found among Aboriginal groups across Australia. In many Australian Aboriginal cultures, the Pleiades are a group of young girls, and are often associated with sacred women’s ceremonies and stories. The Pleiades are also important as an element of Aboriginal calendars and astronomy, and for several groups their first rising at dawn marks the start of winter.

Close to the Seven Sisters in the sky is the constellation of Orion, which is often called “the saucepan” in Australia. In Greek mythology Orion is a hunter. This constellation is also often a hunter in Aboriginal cultures, or a group of lusty young men. The writer and anthropologist Daisy Bates reported people in central Australia regarded Orion as a “hunter of women,” and specifically of the women in the Pleiades. Many Aboriginal stories say the boys, or man, in Orion are chasing the seven sisters—and one of the sisters has died, or is hiding, or is too young, or has been abducted, so again only six are visible.

The Lost Sister

Similar “lost Pleiad” stories are found in European, African, Asian, Indonesian, Native American, and Aboriginal Australian cultures. Many cultures regard the cluster as having seven stars, but acknowledge only six are normally visible, and then have a story to explain why the seventh is invisible.

Why are the Australian Aboriginal stories so similar to the Greek ones? Anthropologists used to think Europeans might have brought the Greek story to Australia, where it was adapted by Aboriginal people for their own purposes. But the Aboriginal stories seem to be much, much older than European contact. And there was little contact between most Australian Aboriginal cultures and the rest of the world for at least 50,000 years. So why do they share the same stories?

Barnaby Norris and I suggest an answer in a paper to be published by Springer early next year in a book titled Advancing Cultural Astronomy, a preprint for which is available here.

All modern humans are descended from people who lived in Africa before they began their long migrations to the far corners of the globe about 100,000 years ago. Could these stories of the seven sisters be so old? Did all humans carry these stories with them as they traveled to Australia, Europe, and Asia?

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Moving Stars

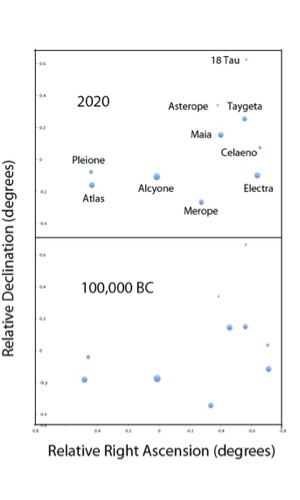

The positions of the stars in the Pleiades today and 100,000 years ago. The star Pleione, on the left, was a bit further away from Atlas in 100,000 BC, making it much easier to see. Credit: Ray Norris

Careful measurements with the Gaia space telescope and others show the stars of the Pleiades are slowly moving in the sky. One star, Pleione, is now so close to the star Atlas they look like a single star to the naked eye.

But if we take what we know about the movement of the stars and rewind 100,000 years, Pleione was further from Atlas and would have been easily visible to the naked eye. So 100,000 years ago, most people really would have seen seven stars in the cluster.

We believe this movement of the stars can help to explain two puzzles: the similarity of Greek and Aboriginal stories about these stars, and the fact so many cultures call the cluster “seven sisters” even though we only see six stars today.

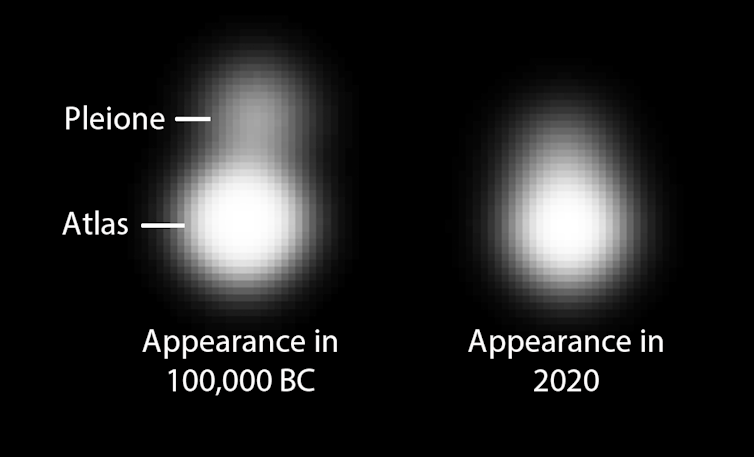

A simulation showing hows the stars Atlas and Pleione would have appeared to a normal human eye today and in 100,000 BC. Image Credit: Ray Norris

Is it possible the stories of the Seven Sisters and Orion are so old our ancestors were telling these stories to each other around campfires in Africa, 100,000 years ago? Could this be the oldest story in the world?

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge and pay our respects to the traditional owners and elders, both past and present, of all the Indigenous groups mentioned in this paper. All Indigenous material has been found in the public domain.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ray Norris is a British/Australian astronomer in the School of Science at Western Sydney University and with CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science. He researches how galaxies formed and evolved after the Big Bang, and the process of astronomical discovery with large data volumes. He also researches the astronomy of Australian Aboriginal people. Ray was educated at Cambridge University, UK, and moved to Australia in 1983 to join CSIRO, where he became Head of Astrophysics in 1994, and then Australia Telescope Deputy Director, and Director of the Australian Astronomy MNRF, before returning in 2005 to active research. He currently leads an international project—the Evolutionary Map of the Universe—to image the faintest radio galaxies in the universe, using the new ASKAP radio telescope recently completed in Western Australia. He also leads the WTF project which is exploring machine learning techniques to discover the unexpected. He frequently appears on radio and TV, and has published a novel, Graven Images.

Related Articles

Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

Scientists Say We Need a Circular Space Economy to Avoid Trashing Orbit

New Images Reveal the Milky Way’s Stunning Galactic Plane in More Detail Than Ever Before

What we’re reading