A Secret to Healthy Aging May Be the Bugs in Your Microbiome

Share

The group of Japanese centenarians had seemingly magical health powers.

Sure, with an average age of 107, they’re among the longest-living humans on Earth. But they were also shockingly healthy, protected from chronic diseases that inevitably haunt us as we age: obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer.

This month, a Japanese study uncovered one piece of their secret. The key to their healthy longevity lies in their guts, or more specifically, in trillions of microbes thriving synergistically as their hosts gracefully age.

What stood out wasn’t the amount of gut bugs. Rather, it was their composition. The gut microbiome is an entire ecosystem, composed of a dazzling number of microbial “species,” each digesting food and pumping out biomolecules. By comparing the gut microbiomes of 160 centenarians with those of the elderly and young, the team found that centenarians had a particular signature to the strains of bacteria in their microbiome.

One strain particularly stood out. Basically living antibiotic factories, the gut bugs readily synthesized a chemical that, when tested in the lab, could knock out one of the toughest infections that causes severe diarrhea and even death. The nature of the superpower chemical raised eyebrows: a type of bile acid, an unglamorous, rather boring bodily fluid commonly known for digesting fat.

“Bile acids are emerging as a new class of ‘enterohormones’ beyond their classic role in fat digestion and absorption,” said Dr. Kim Barrett at UC San Diego, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Rather than “a mere consequence of aging,” these changes in the gut microbiome could potentially protect centenarians against infections and other environmental stressors, helping them maintain their health with age, the authors said. And if bile acids are key, we could conceivably test these chemicals for both battling infection and for longevity.

“This work seems timely, interesting, and important, and to have been carefully conducted. It is certainly conceivable that manipulating concentrations of specific bile acids, whether microbially or by giving them directly, could exert health benefits,” said Barrett.

Gut and Longevity

It’s weird to think that microbes in our gastrointestinal (GI) tract can contribute to longevity. But their impact on our well-being is one of the most mind-boggling health discoveries of the past decade.

The gut is basically an Amazonian forest, densely populated by microbes of all sorts—bacteria, fungi, and viruses. In a healthy human, these are not just benign and along for the ride; they live with us in harmony. The gut bugs capture food as it moves through our alimentary canal, taking in nutrients and secreting their own metabolites—basically, microbial poop.

Similar to animal species, each strain of microbe has its own quirks. Some strains chomp on steak remnants and dose out chemicals that have been linked to inflammatory conditions like heart disease. Others can cause obesity or contribute to Type 2 diabetes. Still others have a direct link to the brain, tapping into a sophisticated neural network that alters anxiety, mood, and even brain development.

The power of the gut microbiota lies in its composition. The ecosystem is a fluid, ever-changing beast. Diet is one trigger. In mice, switching their meals from plant-based vegetarian to cheeseburgers and chocolate changed their microbiome structure within a day. Aging is another: as we age, the microbiome’s composition can shift to correlate with healthy or unhealthy trajectories.

Previous studies with centenarians in Italy and China, for example, found that centenarians carried an abundance of two strains, suggesting those who successfully age also have microbiota that flexibly change and adapt.

The question is: why?

A Behemoth Study

The new study stands out due to its sheer numbers: 160 centenarians, 10 times more than previous efforts at uncovering the link between gut bugs and healthy longevity.

The authors compared these long-living humans’ stool samples—a carrier of gut bugs—with two other groups. One was the elderly, 112 people around 80 years of age; the other had 47 folks below their mid-50s. They then used a tool called metagenomic sequencing, an ultra-fancy DNA sequencing method that detects DNA from a group of samples, to unveil the microbiota strains and their abundance.

At the same time, the team also looked at the metabolites in the participants’ stools. Surprisingly, bile acid genes jumped up in centenarians. But compared to run-of-the-mill bile acids, which usually digest fat, these bile acids came from bacteria rather than from the liver. Similar to acid rain, they changed the gut’s internal pH, suggesting that some microbe strains may preferentially survive.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Digging deeper, the team followed up with a 110-year-old who showed a particularly interesting microbiome profile. They honed in on one group of gut bugs: Odoribacteraceae strains, which churned out a strange bile acid called isoallo-lithocholic acid (isoalloLCA).

That biosynthetic pathway is a “unique profile” that the elderly and younger people didn’t have, the authors said. It was also stable in samples collected over one to two years, even though the authors didn’t control the centenarians’ diets, suggesting it’s not a buggy fluke.

A Powerful Ally

Secondary bile acids are powerful beings. Previous studies in mice, for example, found that they can regulate immune cells and prevent dangerous microbes from taking over the gut.

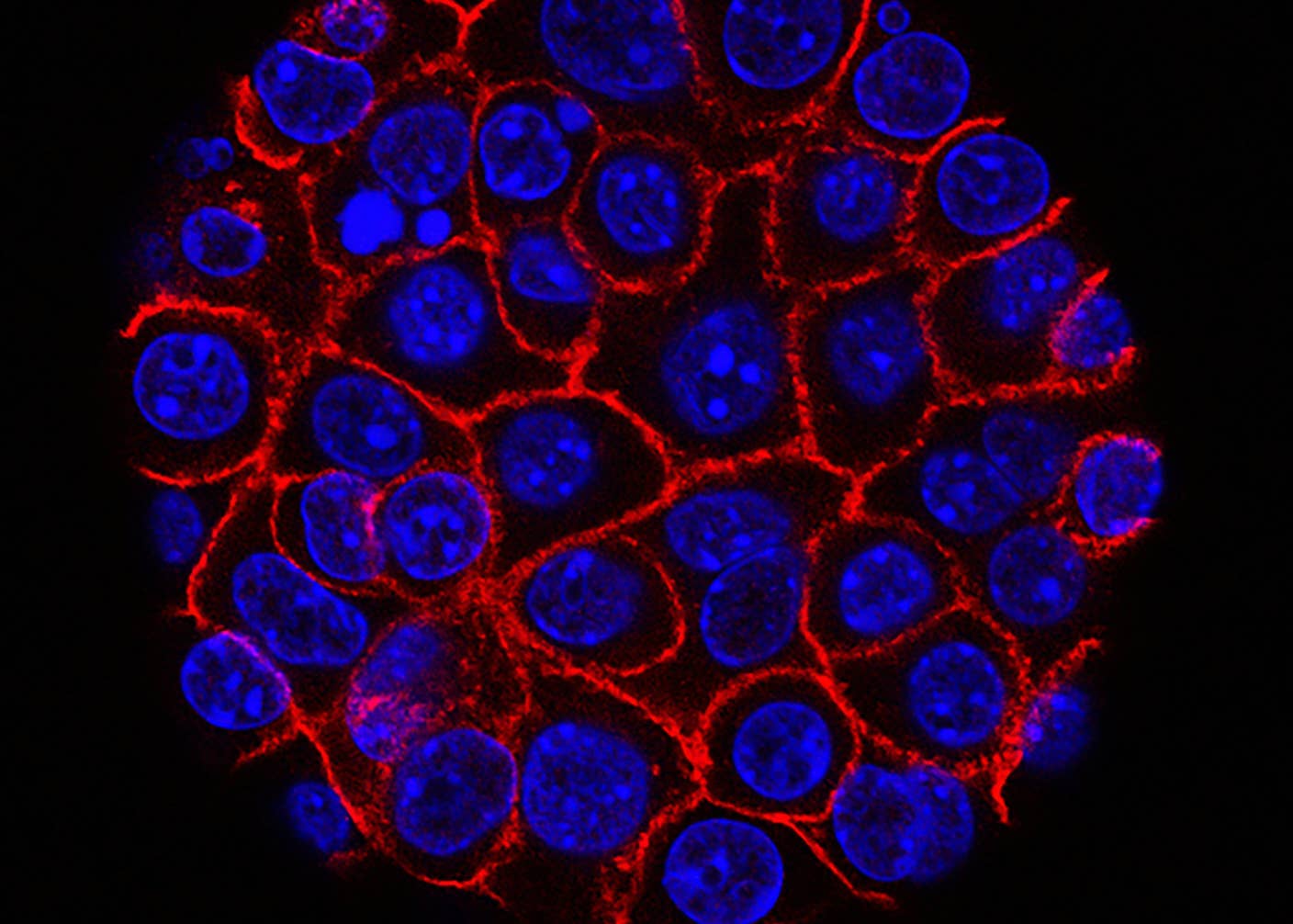

Intrigued by the rise of isoalloLCA in centenarians, the team next sought to see what it does. In one petri dish study, they gave isoalloLCA to Clostridium difficile, a bacteria that causes severe diarrhea in people undergoing antibiotics treatment. “Strikingly,” the team said, “isoalloLCA potently inhibited the growth” of the disease-causing bug, at a far lower dosage than any previously-tested bile acids. Under the microscope, isoalloLCA-treated bacteria swelled up and collapsed into heaps.

"To our knowledge, isoalloLCA is one of the most potent antimicrobial agents selective against gram-positive microbes, including multidrug-resistant pathogens," they wrote.

Further studies found that isoalloLCA could also slaughter other pathogens in a dish and within the body. When mice infected with Clostridium difficile were fed a diet containing the bile acid, their bodies easily eliminated the bug without side effects.

It’s possible, the authors said, that Odoribacteraceae and isoalloLCA can protect the gut from outside invaders, and maintain its health as people age.

“The gut microbiome is emerging as a key factor in the aging process… Abnormal shifts in the gut microbiome, however, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of age-related chronic diseases,” wrote Drs. Minhoo Kim and Berenice Benayoun at the University of Southern California in a previous article (they were not involved in this study).

The results don’t mean a longevity probiotic is coming soon to a store near you. The team will still need to test whether isoalloLCA and other unique bile acids from centenarians can prolong healthy longevity through additional participants and animal studies.

“Like many studies that seek to implicate specific microbiome signatures with particular conditions in humans, as yet the work mostly reveals correlations rather than causality,” said Barrett.

But the study highlights gut bug bile acids as a potential source of health elixirs. “It may be possible to exploit the bile-acid-metabolizing capabilities of the identified bacterial strains to rationally manipulate the pool for health benefits,” the authors said.

Image Credit: WhiteDragon / Shutterstock.com

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

New Device Detects Brain Waves in Mini Brains Mimicking Early Human Development

What we’re reading