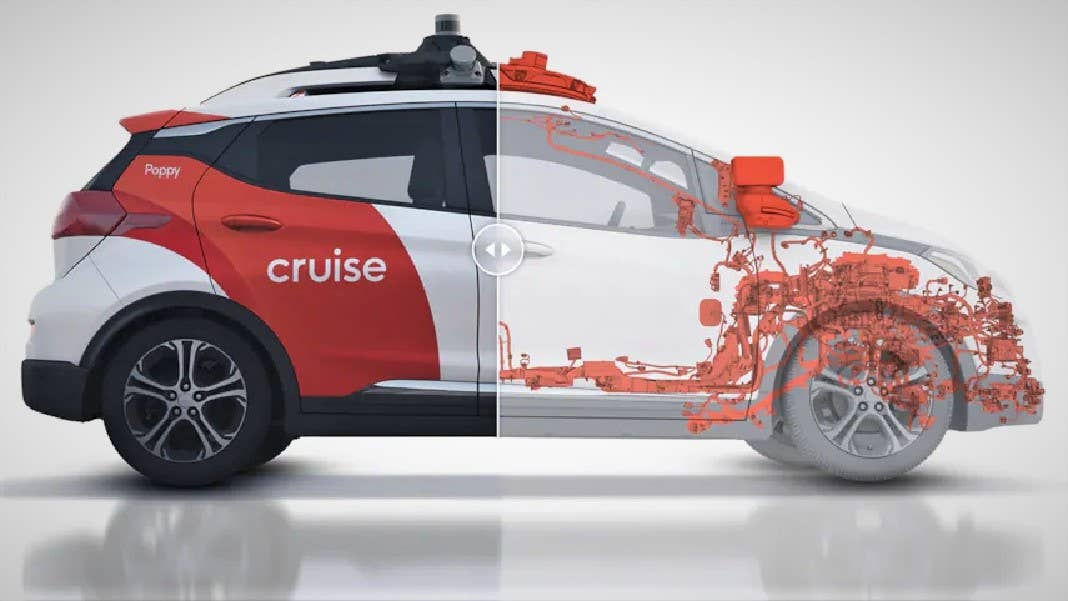

GM Just Patented a Self-Driving Car That Teaches People How to Drive

Share

For more than a decade, people have been trying to teach cars how to drive. In the not-too-distant future, this effort may come full circle, with cars teaching people how to drive; last week, General Motors applied for a patent on an autonomous vehicle equipped to “train drivers.”

Self-driving cars have taken a lot longer to come about than was predicted, with complications relating to technology, safety, and regulations all throwing wrenches in the spokes of progress. Google was one of the first companies to invest heavily in driverless vehicle development, launching its self-driving car project in early 2009 out of its X lab (also known as the Moonshot Factory).

As recently as 2015, auto industry insiders predicted fully self-driving cars would be on the road by 2020. That wasn't the case, and two years later we’re still waiting for the day we can kick back, put our feet up, and watch the scenery go by as autonomous cars deliver us to our destinations.

It seems General Motors thinks that day isn’t too far off, and the company wants to take self-driving tech one step further by turning the tables: what if cars could teach people to drive?

If, like me, your first thought was: why would people need to know how to drive in a future where cars are self-driving? It’s a valid question, particularly because some of the more recent driverless car designs don’t even have a steering wheel. But GM’s patent application notes that despite the existence of self-driving cars in the future, people may not always have access to them, may be in a location or situation where they’re not allowed, or “may wish to drive for personal satisfaction.”

The application further notes that until now, humans have taught other humans to drive, but drawbacks of human instruction include that it can be expensive and time-consuming (remember doing 25 hours of behind-the-wheel time in driver’s ed? I sure do), can include elevated risks and inefficiencies, and can cause teachers to pass on biases to students. The latter argument is vague, as beyond following universal rules of the road, everyone is bound to drive a little differently.

GM’s car would teach people to drive using sensors and real-time feedback. An on-board processor determines an action for the driver, and when the driver takes that action—say, completing a left turn at a crowded intersection as the stoplight turns from green to yellow—the car would compare the driver’s actions to what its algorithm would have done, then generate a score according to how closely the driver’s performance matched the car’s specifications.

The car could also “selectively allow” the trainee to control as much or as little driving functionality as it deems appropriate based on the driver’s performance. If hanging a left at that busy intersection nearly causes a collision with another car, pedestrian, etc., GM’s vehicle would take note and determine that this student needs some help, pronto, and disable the accelerator while its computer takes over.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Finally, the car would provide results about driver performance to third parties, like human instructors or parents.

The patent application doesn’t specify whether the car would provide real-time feedback to drivers via audio or another means, such as a display screen on the dashboard, but it seems most plausible that the car would “talk” to drivers, as taking their focus off the road to look at a screen wouldn’t be a great call (not that we don’t all do that every time we drive, ahem).

Self-driving cars are themselves still years away from becoming mainstream. But it’s not too far-fetched to imagine driving schools using a tool like GM’s training car to help students get in more road hours without being totally unsupervised.

Ultimately, though—decades in the future—tech companies would have us believe we won’t need to know how to drive at all; cars will be doing 100 percent of the work, and we’ll be better off for it. Or that's the goal, at least.

Image Credit: Cruise

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

These Robots Are the Size of Single Cells and Cost Just a Penny Apiece

In Wild Experiment, Surgeon Uses Robot to Remove Blood Clot in Brain 4,000 Miles Away

A Squishy New Robotic ‘Eye’ Automatically Focuses Like Our Own

What we’re reading