This Newly Discovered Super-Earth May Be an Ocean Planet Shrouded in the Deepest of Seas

Share

This week, scientists announced that the James Webb Space Telescope, which among its many talents can analyze the atmospheres of exoplanets, just confirmed the presence of carbon dioxide on a world orbiting a sun some 700 light-years away. It's the first observation of CO2 in a planetary atmosphere beyond our solar system.

But that discovery, made about a world very unlike our own, is just the first taste of what Webb's instruments may soon reveal. Astronomers are eager to focus the telescope on planets like Earth, where liquid water, a crucial ingredient for life as we know it, is abundant. In the coming months and years, they will undoubtedly get their chance.

There are a number of promising Earth-like planets Webb could study in the near future, but in a paper published recently in The Astronomical Journal, scientists from the University of Montreal argue they've discovered one of the best such candidates yet.

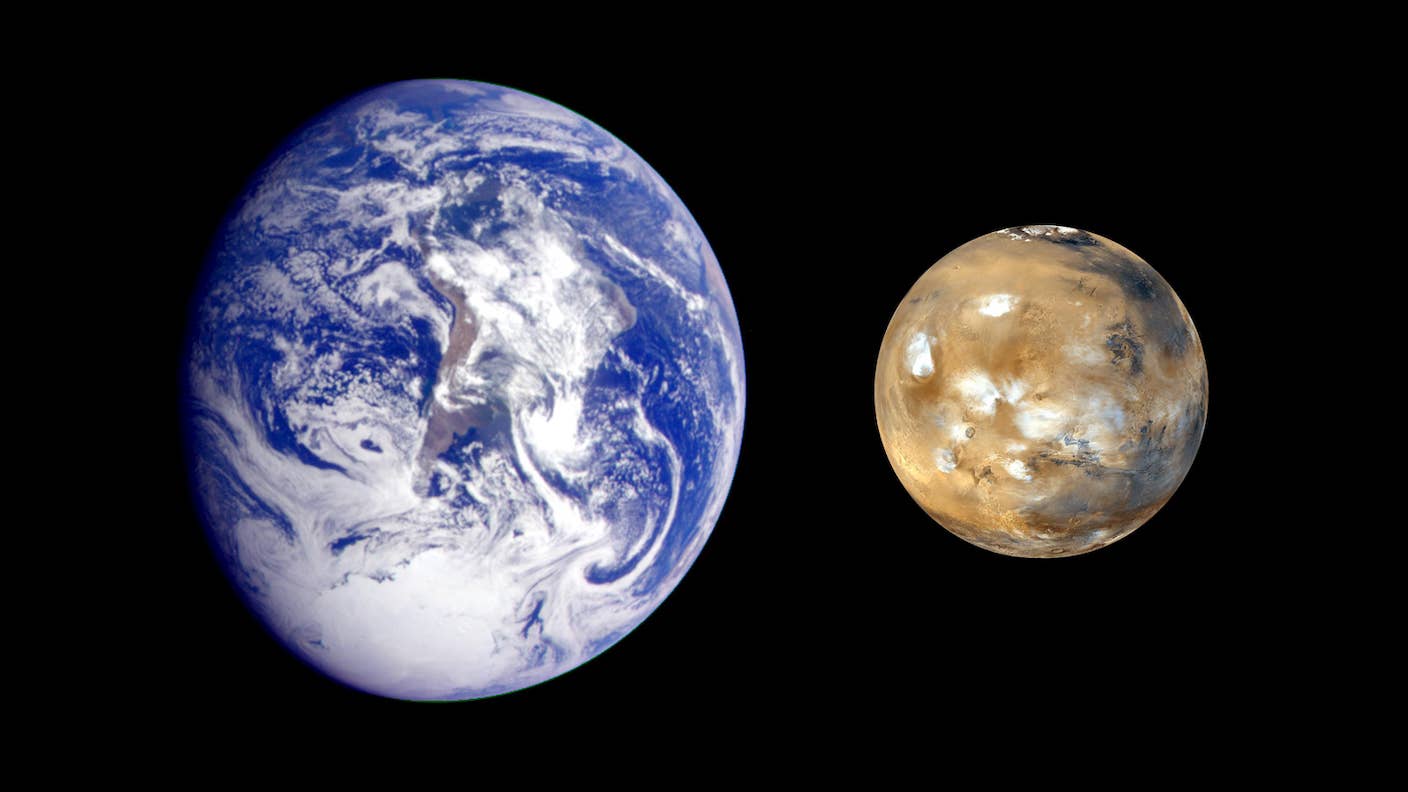

The planet, orbiting a star in the binary system TOI-1452, is 100 light-years away. It's about 70% bigger than Earth—a type of exoplanet called a super-Earth—and orbits in a region scientists call the habitable zone where liquid water is possible. More tantalizing still, however, is the fact the planet's density hints at the presence of a global ocean.

Water World

Scientists first spied TOI-1452 b in data gathered by the TESS space telescope. The team further confirmed the planet's existence and pinned down key attributes with ground-based observations. By measuring how much an orbiting planet makes its parent star wobble, researchers can estimate its mass, while analysis of how much light it blocks as it moves between its star and Earth yields estimates of its size.

TOI-1452 b is circling a red dwarf star that's smaller and dimmer than our sun. So, while the planet is in a tight orbit relative to Earth—completing a circuit around its star every 11 days—it receives about the same amount of solar radiation as Venus. That puts it smack in the middle of the habitable zone. Taken together with its surprisingly low density, a leading theory is that TOI-1452 b is a water world.

One model in the study estimated water could make up 30 percent of the planet's mass. By comparison, water covers 70 percent of Earth's surface but is only 1 percent of its mass. So if the model proves accurate, TOI-1452 b's entire surface could be covered by a global ocean far deeper than any on Earth.

"TOI-1452 b is one of the best candidates for an ocean planet that we have found to date," said Charles Cadieux, an astronomer at the University of Montreal and the new paper's lead author. "Its radius and mass suggest a much lower density than what one would expect for a planet that is basically made up of metal and rock, like Earth."

The key word is candidate. The data leaves plenty of room for uncertainty as to whether TOI-1452 is actually an ocean planet. The paper also explores scenarios in which it is a rocky world with no atmosphere or rocky with an extended atmosphere of light gases like hydrogen and helium. The only way to know for sure is to take a look.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The Next Blue Marble

As light shines through exoplanet atmospheres, the various chemical constituents absorb signature wavelengths. The resulting spectrum is like a fingerprint of the atmosphere's chemical makeup, the gaps announcing the presence of various elements like hydrogen and helium or molecules like water vapor. Until now, however, our ability to directly analyze exoplanet atmospheres, especially those around smaller planets, has been limited.

But with Webb, humanity has a new pair of glasses more than up to the job. In addition to TOI-1452 b's physical attributes, the planet is also relatively close to Earth, and its position in the sky is available for observation year-round. The scientists say they hope to book time on the telescope soon to directly confirm or reject their hypothesis.

Whether this particular planet pans out is somewhat beside the point. What's more exciting is our new ability to peek into the atmospheres of a list of promising planets light-years distant. It's entirely possible that scientists will soon locate and confirm an ocean world orbiting another star: The first blue marble beyond our solar system.

From there, we may find many more marbles, and while Webb wasn't explicitly designed to detect biosignatures—the chemical fingerprints of life itself—upcoming telescopes will be. These include the ground-based Giant Magellan Telescope, the Thirty Meter Telescope, and the European Extremely Large Telescope.

As our rolodex of confirmed ocean planets grows, so too does the list of promising targets for future telescopes to train their sights on, and in what would undoubtedly be a world-shaking discovery, we may finally spy the first signs of life in the lonely void.

Image Credit: Benoit Gougeon, University of Montreal

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

More Space Junk Is Plummeting to Earth. Earthquake Sensors Can Track It by the Sonic Booms.

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

What we’re reading