A California Startup Says 3D Printing Batteries Could Double Capacity

Share

Solid-state batteries could be more energy dense, safer, and faster charging than today's technology, but finding a way to make them commercially viable is challenging. One company thinks 3D printing holds the answer.

In recent years, the lithium-ion batteries that power everything from smartphones to electric vehicles have seen huge improvements in their safety and energy density (a measure of how much power they pack in per pound). But progress is slowing, and it seems likely that we will need to switch to novel battery designs if we want to banish the gas-powered car to the history books.

Solid-state batteries, which replace the liquid electrolyte found in today’s cells with a solid one, are some of the most promising candidates in the near term. They would not only make batteries safer by removing the flammable liquid electrolyte, but could also boost energy density and allow faster charging.

A number of startups have developed promising prototypes, but working out how to manufacture these kinds of batteries at scale is a major challenge. California-based startup Sakuú thinks the answer is to use 3D printing, which would allow them to make much more efficient use of space and therefore produce batteries with much higher capacity than competitors.

Batteries are made up of three key components: a positive electrode called an anode, a negative electrode called a cathode, and an electrolyte that allows ions to travel between the two. In today’s most advanced lithium-ion batteries, the electrodes are made using a production process known as “roll-to-roll” manufacturing.

The materials used to make each of the electrodes are mixed into a slurry and then coated onto a long roll of metal foil before being dried. These long rolls are then sliced up into smaller sections and stacked on top of each other with a separator between each electrode. These stacks are placed in an enclosure that is then filled with liquid electrolyte.

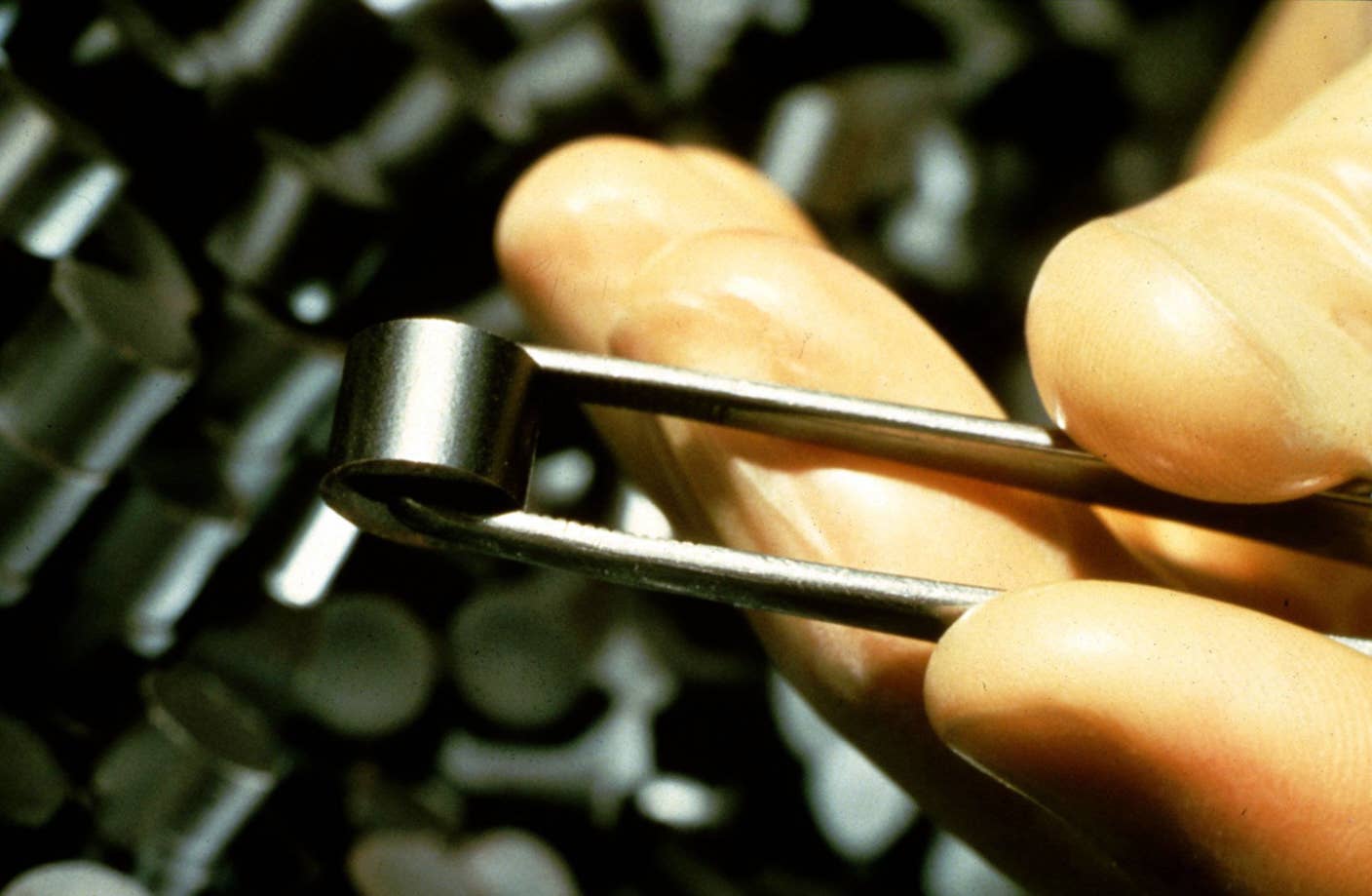

Even newer solid-state battery companies are proposing to use the same production process, but Sakuú is taking a completely different approach. It has created a 10-meter-long multi-material printer that can work with both ceramics and metals. The machine first lays down patterns of powdered material before depositing a jet of polymer binder that sticks the particles together. It then deposits conductive metal on top. These layers are stacked on top of each other to produce cells.

The company told The Verge that the approach allows it to stack more layers into a given space than conventional approaches. On its website, Sakuú claims this is because its manufacturing process allows for thinner structural layers and a novel stacked structure. This means it can either provide 100 percent greater capacity than current lithium-ion cells, or make batteries 50 percent smaller and 40 percent lighter.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Another attractive benefit of using 3D printing is that it should be possible to build batteries in all kinds of different shapes, which is difficult with traditional roll-to-roll manufacturing. This could make it possible to build batteries into the structure of products rather than having to dedicate space for them.

This is something that has become a major focus for the electric vehicle industry, as companies attempt to boost the battery capacity of their vehicles without adding extra weight. Chinese battery maker Contemporary Amperex Technology and electric vehicle Leapmotor are working on ways to build batteries into the chassis of cars, while Tesla says it has devised a new glue that will make its batteries load-bearing, allowing them to be used as structural parts.

The ability to 3D print batteries in a variety of shapes could turbocharge this trend, but it’s likely to be some time before Sakuú’s batteries hit the road. While it told The Verge that each of its printers will eventually be able to churn out about 40 megawatt hours of energy storage—the equivalent of 500 electric car batteries—so far it only has a prototype of its machine, and it has not yet been used to make any batteries.

If they can get their printers up and running, though, this could provide a big boost to efforts to increase the range and reliability of electric vehicles and push them further into the mainstream.

Image Credit: Sakuú

Related Articles

Meta Will Buy Startup’s Nuclear Fuel in Unusual Deal to Power AI Data Centers

Your ChatGPT Habit Could Depend on Nuclear Power

Hugging Face Says AI Models With Reasoning Use 30x More Energy on Average

What we’re reading