NASA Will Buy Lunar Dust in the First Commercial Transaction on the Moon

Share

Private companies are playing an ever greater role in space, in many cases with the blessing of national space agencies. Now Japan has issued a startup the first-ever license to conduct business activity on the moon, which could change the face of lunar exploration.

SpaceX’s rapid ascent to become one of the world’s premier launch providers in just a couple of decades has opened peoples’ eyes to the dynamism private enterprise can bring to the space industry. While the US is leading the way, a growing number of countries are pushing to develop commercial space sectors of their own.

While there’s already a robust market for taking satellites into space, national space agencies are keen to encourage companies to look beyond Earth’s orbit as well. For many, the long-term goal is to create a bustling space economy that can help to support missions that venture further into the solar system.

To that end, several countries have passed laws that allow firms to extract and use space resources, in the hope that this will provide a business case for more adventurous private missions. And now Japan has issued a license under its 2021 Space Resources Act that will allow Tokyo-based startup ispace to collect and sell a small amount of lunar soil to NASA under a pre-agreed contract.

“If ispace transfers ownership of lunar resources to NASA in accordance with its plan, it will be the first case in the world of commercial transactions of space resources on the moon by a private operator,” Sanae Takaichi, Japan’s Minister of State for Space Policy, said at a press conference. “This will be a groundbreaking first step toward the establishment of commercial space exploration by private operators.”

The company is planning to launch its Hakuto-R lander to the moon on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket as soon as November 22. The vehicle will help deliver a variety of commercial and government payloads to the moon, including two rovers, as well as fulfilling the contract with NASA.

The transaction is not destined to be a very lucrative one for ispace, though. In 2020, NASA agreed to contracts with four space companies to collect lunar regolith—the mixture of rock and dust that makes up the moon’s surface—and sign over ownership of it to the space agency. According to the agreement, ispace will receive a paltry $5,000 for its efforts.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Admittedly, the company hasn’t expended much technical effort on the collection mission. Its plan is to simply sell NASA whatever dirt accumulates on its lander’s footpads, and it’s under no obligation to bring the regolith back to Earth. That’s because the contract isn’t actually about NASA getting hold of a small pile of moon dust; it is designed to set a precedent that private companies can extract and sell resources on the moon.

That has proven controversial. The US has been actively promoting the commercial exploitation of space resources, in particular through a series of bilateral agreements with other countries called the Artemis Accords. Like Japan, it has also signed national legislation allowing companies rights over resources they extract, as have two other Artemis signatories: Luxembourg and the United Arab Emirates.

But Russia has voiced opposition to this approach. Last year the director general of Roscosmos, Dmitry Rogozin, said that countries shouldn’t be using domestic legislation to make unilateral decisions about how to deal with space resources. Outer space belongs to everyone, and how it is exploited should be decided at the multilateral level, he said, for instance at the United Nations.

That appeal seems to have fallen on deaf ears, though. Assuming ispace’s launch is successful, the commercialization of the moon may begin in just a few months. Whether that marks the beginning of a free-for-all dash for lunar resources or the start of a sustainable space economy remains to be seen.

Image Credit: ispace

Related Articles

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

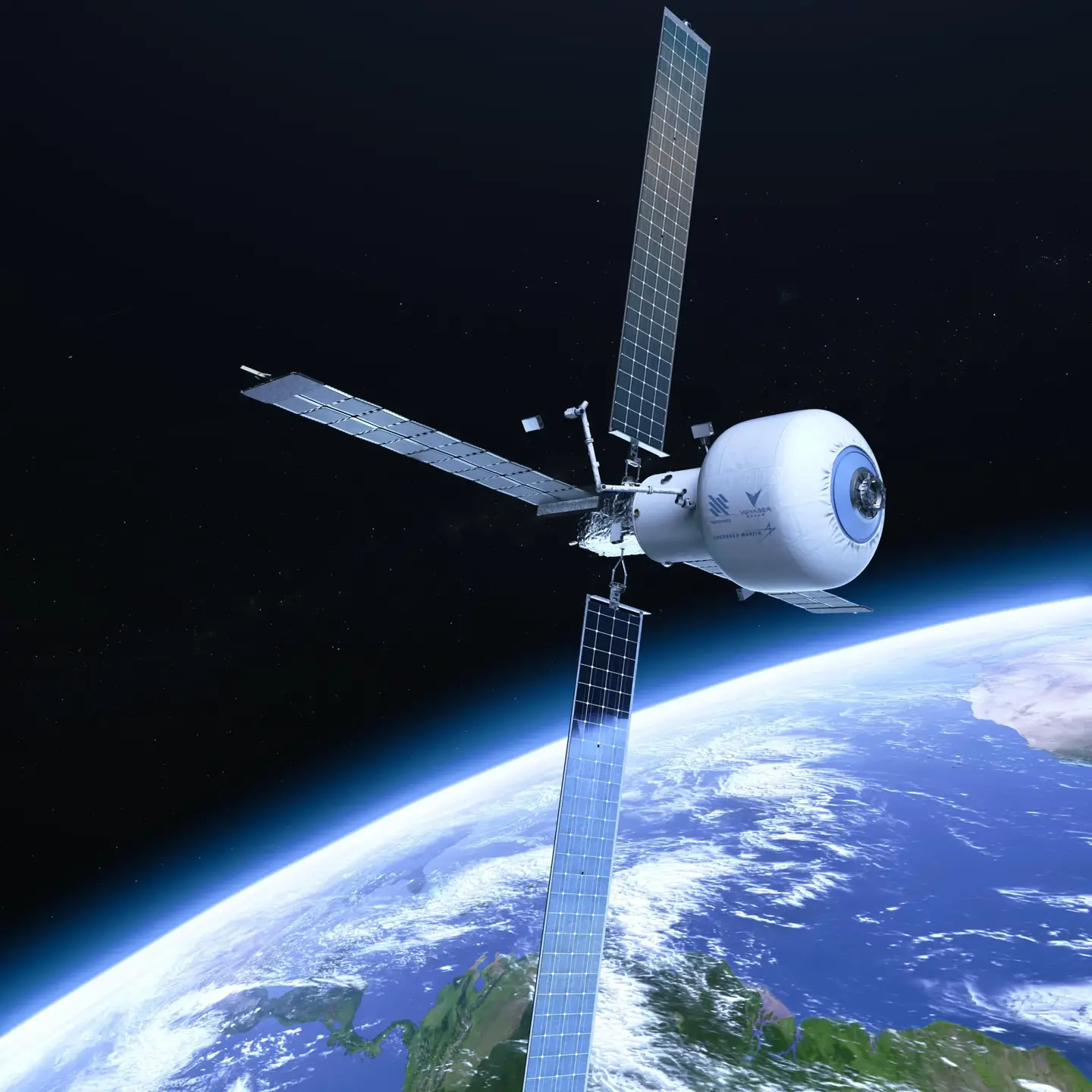

The Era of Private Space Stations Launches in 2026

What we’re reading