AI Might Be Seemingly Everywhere, but There Are Still Plenty of Things It Can’t Do—For Now

Share

These days, we don’t have to wait long until the next breakthrough in artificial intelligence impresses everyone with capabilities that previously belonged only in science fiction.

In 2022, AI art generation tools such as Open AI’s DALL-E 2, Google’s Imagen, and Stable Diffusion took the internet by storm, with users generating high-quality images from text descriptions.

Unlike previous developments, these text-to-image tools quickly found their way from research labs to mainstream culture, leading to viral phenomena such as the “Magic Avatar” feature in the Lensa AI app, which creates stylized images of its users.

In December, a chatbot called ChatGPT stunned users with its writing skills, leading to predictions the technology will soon be able to pass professional exams. ChatGPT reportedly gained one million users in less than a week. Some school officials have already banned it for fear students would use it to write essays. Microsoft is reportedly planning to incorporate ChatGPT into its Bing web search and Office products later this year.

What does the unrelenting progress in AI mean for the near future? And is AI likely to threaten certain jobs in the following years?

Despite these impressive recent AI achievements, we need to recognize there are still significant limitations to what AI systems can do.

AI Excels at Pattern Recognition

Recent advances in AI rely predominantly on machine learning algorithms that discern complex patterns and relationships from vast amounts of data. This training is then used for tasks like prediction and data generation.

The development of current AI technology relies on optimizing predictive power, even if the goal is to generate new output.

For example, GPT-3, the language model behind ChatGPT, was trained to predict what follows a piece of text. GPT-3 then leverages this predictive ability to continue an input text given by the user.

“Generative AIs” such as ChatGPT and DALL-E 2 have sparked much debate about whether AI can be genuinely creative and even rival humans in this regard. However, human creativity draws not only on past data but also on experimentation and the full range of human experience.

Cause and Effect

Many important problems require predicting the effects of our actions in complex, uncertain, and constantly changing environments. By doing this, we can choose the sequence of actions most likely to achieve our goals. But algorithms cannot learn about causes and effects from data alone. Purely data-driven machine learning can only find correlations.

To understand why this is a problem for AI, we can contrast the problems of diagnosing a medical condition versus choosing a treatment. Machine learning models are often helpful for finding abnormalities in medical images; this is a pattern recognition problem. We don’t need to worry about causality because abnormalities are already either present or not.

But choosing the best treatment for a diagnosis is a fundamentally different problem. Here, the goal is to influence the outcome, not just recognize a pattern. To determine the effectiveness of a treatment, medical researchers run randomized controlled trials. This way, they can try to control any factors that might affect the treatment.

The confusion between these two types of problems sometimes leads to suboptimal applications of machine learning in organizations.

While the success of recent work in AI demonstrates the value of data-driven models, many of the problems we would want computers to solve require an understanding of causation.

Current AI systems lack this ability, apart from specialized applications such as board games.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Common Sense Reasoning

Language models such GPT-3 and ChatGPT can successfully solve some tasks requiring common-sense reasoning.

However, the following interaction with ChatGPT, adapted from an experiment by Gary Marcus, suggests it is not entirely reliable in this respect.

"I’m eight years old. When I was born, my biological mother was in Barcelona and my father was in Tokyo. Where was I born? Think through this step by step.

It is not mentioned where you were born. All we know is that your biological mother was in Barcelona and your father was in Tokyo at the time of your birth."

Whether AI systems such as ChatGPT can achieve common sense is a subject of lively debate among experts.

Sceptics such as Marcus point out we cannot trust language models to robustly display common sense since they neither have it built into them nor are directly optimized for it. Optimists argue that while current systems are imperfect, common sense may spontaneously emerge in sufficiently advanced language models.

Human Values

Whenever groundbreaking AI systems are released, news articles and social media posts documenting racist, sexist, and other types of biased and harmful behaviors inevitably follow.

This flaw is inherent to current AI systems, which are bound to be a reflection of their data. Human values such as truth and fairness are not fundamentally built into the algorithms; that’s something researchers don’t yet know how to do.

While researchers are learning the lessons from past episodes and making progress in addressing bias, the field of AI still has a long way to go to robustly align AI systems with human values and preferences.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

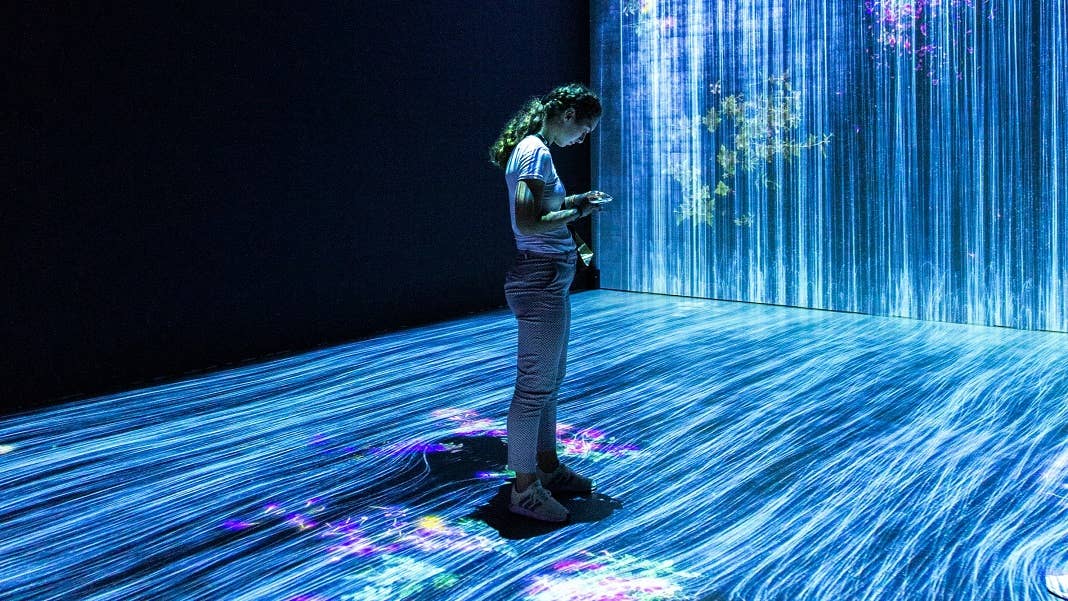

Image Credit: Mahdis Mousavi/Unsplash

Marcel Scharth is a Lecturer in Business Analytics at the University of Sydney Business School. He specializes in the fields of statistics, econometrics, machine learning, and data science. Marcel received his Ph.D. from the VU University Amsterdam and the Tinbergen Institute in 2012, and has previously worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of New South Wales. Marcel is also affiliated with the Centre for Translational Data Science at the University of Sydney, where he engages in cross-disciplinary research in collaboration with partners in academia and industry.

Related Articles

Hugging Face Says AI Models With Reasoning Use 30x More Energy on Average

Study: AI Chatbots Choose Friends Just Like Humans Do

AI Companies Are Betting Billions on AI Scaling Laws. Will Their Wager Pay Off?

What we’re reading