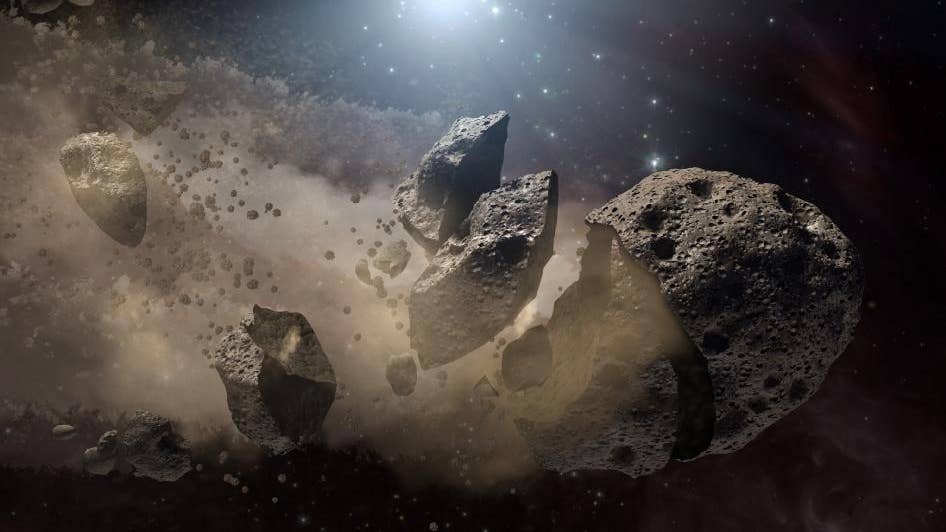

Earth Will Likely Dodge ‘Planet Killer’ Asteroids for the Next 1,000 Years

Share

To those who study existential risk, the list of threats is lengthening. If nuclear war doesn't end us, a designer virus or AI might. The good news? No giant asteroids will strike this millennium.

A new study by University of Colorado and NASA scientists and accepted for publication in The Astronomical Journal, extended forecasts for the biggest known near-Earth asteroids by an order of magnitude and found none threaten Earth in the next thousand years.

Don't Look Up

In 1998, NASA asked scientists to find 90 percent of all near-Earth asteroids bigger than a kilometer. The 10-kilometer-wide asteroid that killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago belonged to this club. But even smaller strikes would be catastrophic.

“This is what we call a planet killer,” astronomer Scott Sheppard told the New York Times last year after scientists found a new 1.5-kilometer asteroid. “If this one hits the Earth, it would cause planet-wide destruction. It would be very bad for life as we know it.”

Scientists believe such impacts happen every few million years, but until recent decades, there was simply no way to predict future strikes. No one had a list of likely candidates. NASA has since discovered nearly a thousand asteroids over a kilometer wide, or around 95 percent of the total in existence.

This catalog includes observations that help astronomers calculate each asteroid's orbit and model the likelihood it'll impact Earth in the future. But these predictions previously maxed out around a hundred years. As asteroids careen around the sun, their orbits are tugged about by the gravity of the planets. Gravitational encounters, especially close ones, increase the uncertainty in forecasting models. Past a certain point, astronomers can't say exactly where an asteroid will be in its orbit.

Buzzing the Tower

The new study aims to make longer forecasts by employing some tricks to reduce the computational workload. Instead of relying on orbital position alone, they zoomed in on the most consequential moments—close flybys of Earth. These encounters, they write, can be modeled further into the future, even as orbital position becomes uncertain.

Looking ahead a thousand years, the team found the vast majority of asteroids didn't spend much time in our neighborhood and could be ruled out as hazardous. Next, they identified the population of large asteroids that most frequently buzz by Earth. Using their new method, they modeled close encounters over the next millennium.

The asteroid with the highest probability of impact is 1994 PC1, a kilometer-wide asteroid that passes close to Earth often. The team found a 0.00151 percent chance that 1994 PC1 would pass within the moon's orbit in the next thousand years. This is a very small risk—and yet it's still ten times higher than any other asteroid on the list.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Using this method at least, it seems we're very unlikely to experience a major impact any time soon.

"It's still not likely that it's going to collide," the University of Colorado's Oscar Fuentes-Muñoz, who led the team, told MIT Technology Review. "But it will be a very good scientific opportunity, because it's going to be a huge asteroid that's very close to us."

Planetary Defense

Of course, there's a chance a more dangerous asteroid is lurking in the still-undiscovered five percent of kilometer-sized objects. The space rock Sheppard was referring to last year is a member of a group of large asteroids hiding in the glare of the sun. And large comets living out in the Kuiper Belt and Oort cloud could be nudged into our path one day. But the most likely interlopers are nearby, and we're getting a much better handle on their habits.

The team write they'd like to apply their approach to extend forecasts for smaller asteroids too. There are a lot more of those—around 25,000 are thought to be bigger than 140 meters, of which we've only discovered around 40 percent—and while they wouldn't cause planet-wide destruction, they could certainly wreak havoc regionally or, if our luck is especially bad, in areas with high population densities, like cities.

Still, the forecast is encouraging. The likelihood of a significant strike soon is very low. Should we discover a dangerous smaller asteroid in the future, NASA's DART mission last year showed we might push it off-course and prevent a strike with enough advance warning. And although there's no proven way of avoiding the biggest impacts—we can breathe easier knowing we likely have another thousand years to strengthen our defenses.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

More Space Junk Is Plummeting to Earth. Earthquake Sensors Can Track It by the Sonic Booms.

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What we’re reading