Here’s How Nvidia’s Vice-Like Grip on AI Chips Could Slip

Share

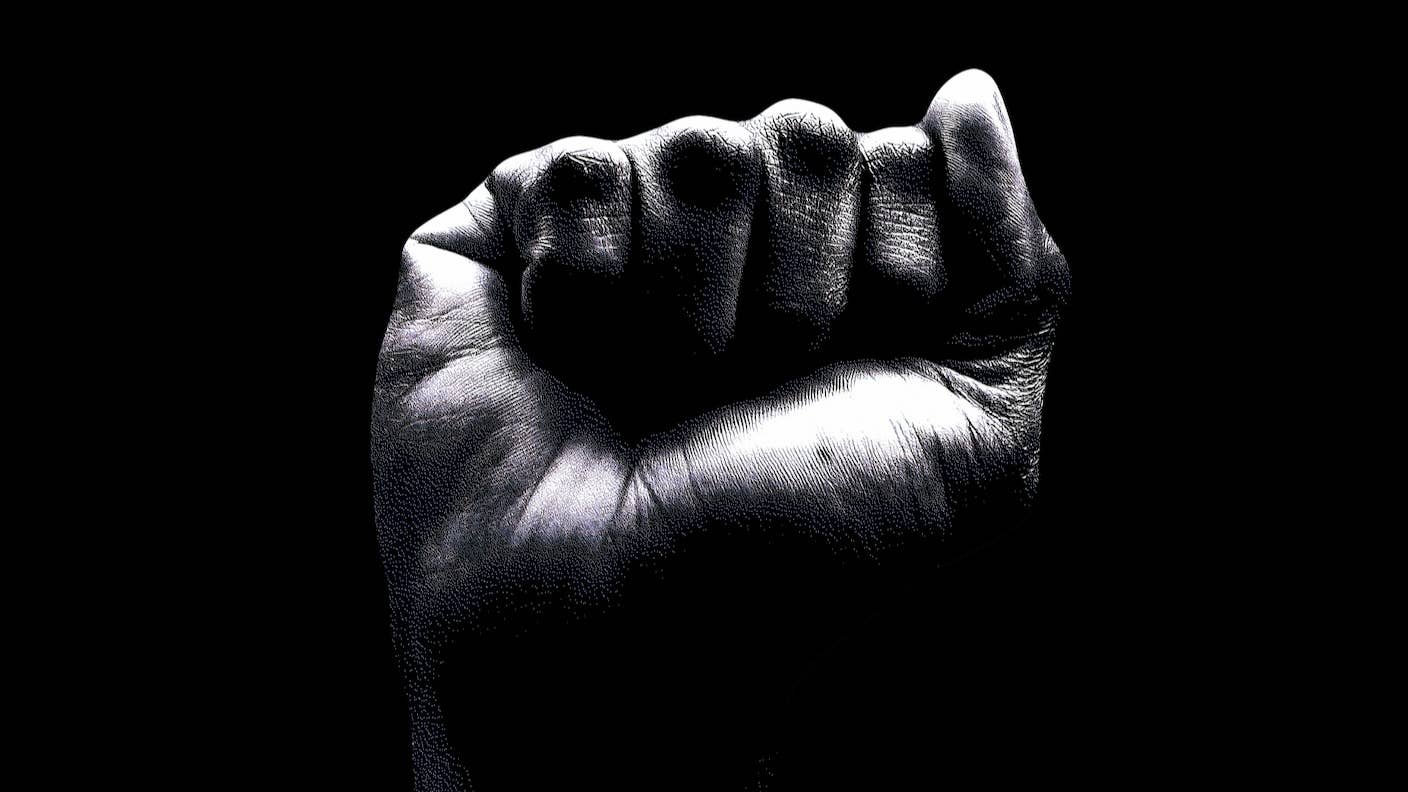

In the great AI gold rush of the past couple of years, Nvidia has dominated the market for shovels—namely the chips needed to train models. But a shift in tactics by many leading AI developers presents an opening for competitors.

Nvidia boss Jensen Huang’s call to lean into hardware for AI will go down as one of the best business decisions ever made. In just a decade, he’s converted a $10 billion business that primarily sold graphics cards to gamers into a $3 trillion behemoth that has the world’s most powerful tech CEOs literally begging for his product.

Since the discovery in 2012 that the company’s graphics processing units (GPUs) can accelerate AI training, Nvidia’s consistently dominated the market for AI-specific hardware. But competitors are nipping at its heels, both old foes, like AMD and Intel, as well as a clutch of well-financed chip startups. And a recent change in priorities at the biggest AI developers could shake up the industry.

In recent years, developers have focused on training ever-larger models, something at which Nvidia’s chips excel. But as gains from this approach dry up, companies are instead boosting the number of times they query a model to squeeze out more performance. This is an area where rivals could more easily compete.

"As AI shifts from training models to inference, more and more chip companies will gain an edge on Nvidia,” Thomas Hayes, chairman and managing member at Great Hill Capital, told Reuters following news that custom semiconductor provider Broadcom had hit a trillion-dollar valuation thanks to AI chips demand.

The shift is being driven by the cost and sheer difficulty of getting ahold of Nvidia’s most powerful chips, as well as a desire among AI industry leaders not to be entirely beholden to a single supplier for such a crucial ingredient.

The competition is coming from several quarters.

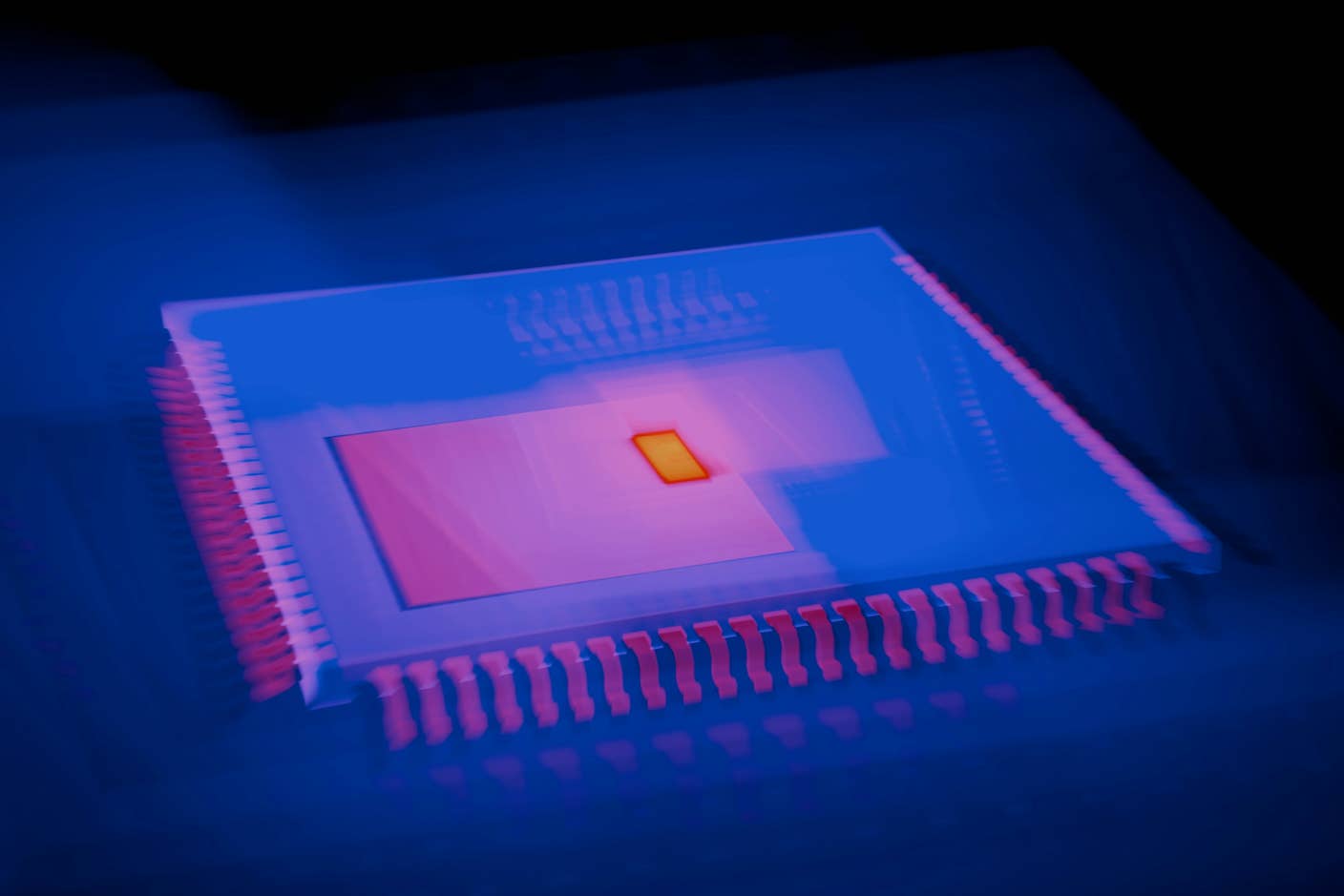

While Nvidia’s traditional rivals have been slow to get into the AI race, that’s changing. At the end of last year, AMD unveiled its MI300 chips, which the company’s CEO claimed could go toe-to-toe with Nvidia’s chips on training but provide a 1.4x boost on inference. Industry leaders including Meta, OpenAI, and Microsoft announced shortly afterwards they would use the chips for inference.

Intel has also committed significant resources to developing specialist AI hardware with its Gaudi line of chips, though orders haven’t lived up to expectations. But it’s not only other chipmakers trying to chip away at Nvidia’s dominance. Many of the company’s biggest customers in the AI industry are also actively developing their own custom AI hardware.

Google is the clear leader in this area, having developed the first generation of its tensor processing unit (TPU) as far back as 2015. The company initially developed the chips for internal use, but earlier this month it announced its cloud customers could now access the latest Trillium processors to train and serve their own models.

While OpenAI, Meta, and Microsoft all have AI chip projects underway, Amazon recently undertook a major effort to catch up in a race it’s often seen as lagging in. Last month, the company unveiled the second generation of its Trainium chips, which are four times faster than their predecessors and already being tested by Anthropic—the AI startup in which Amazon has invested $4 billion.

The company plans to offer data center customers access to the chip. Eiso Kant, chief technology officer of AI start-up Poolside, told the New York Times that Trainium 2 could boost performance per dollar by 40 percent compared to Nvidia chips.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Apple too is, allegedly, getting in on the game. According to a recent report by tech publication The Information, the company is developing an AI chip with long-time partner Broadcom.

In addition to big tech companies, there are a host of startups hoping to break Nvidia’s stranglehold on the market. And investors clearly think there’s an opening—they pumped $6 billion into AI semiconductor companies in 2023, according to data from PitchBook.

Companies like SambaNova and Groq are promising big speedups on AI inference jobs, while Cerebras Systems, with its dinner-plate-sized chips, is specifically targeting the biggest AI computing tasks.

However, software is a major barrier for those thinking of moving away from Nvidia’s chips. In 2006, the company created proprietary software called CUDA to help developers design programs that operate efficiently over many parallel processing cores—a key capability in AI.

“They made sure every computer science major coming out of university is trained up and knows how to program CUDA,” Matt Kimball, principal data-center analyst at Moor Insights & Strategy, told IEEE Spectrum. “They provide the tooling and the training, and they spend a lot of money on research.”

As a result, most AI researchers are comfortable in CUDA and reluctant to learn other companies’ software. To counter this, AMD, Intel, and Google joined the UXL Foundation, an industry group creating open-source alternatives to CUDA. Their efforts are still nascent, however.

Either way, Nvidia’s vice-like grip on the AI hardware industry does seem to be slipping. While it’s likely to remain the market leader for the foreseeable future, AI companies could have a lot more options in 2025 as they continue building out infrastructure.

Related Articles

Scientists Send Secure Quantum Keys Over 62 Miles of Fiber—Without Trusted Devices

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

What we’re reading