China Is About to Build the World’s Biggest Hydropower Dam—With Triple the Output of Three Gorges

Medog Hydropower Station, as it will be called, will blow other hydropower dams out of the water.

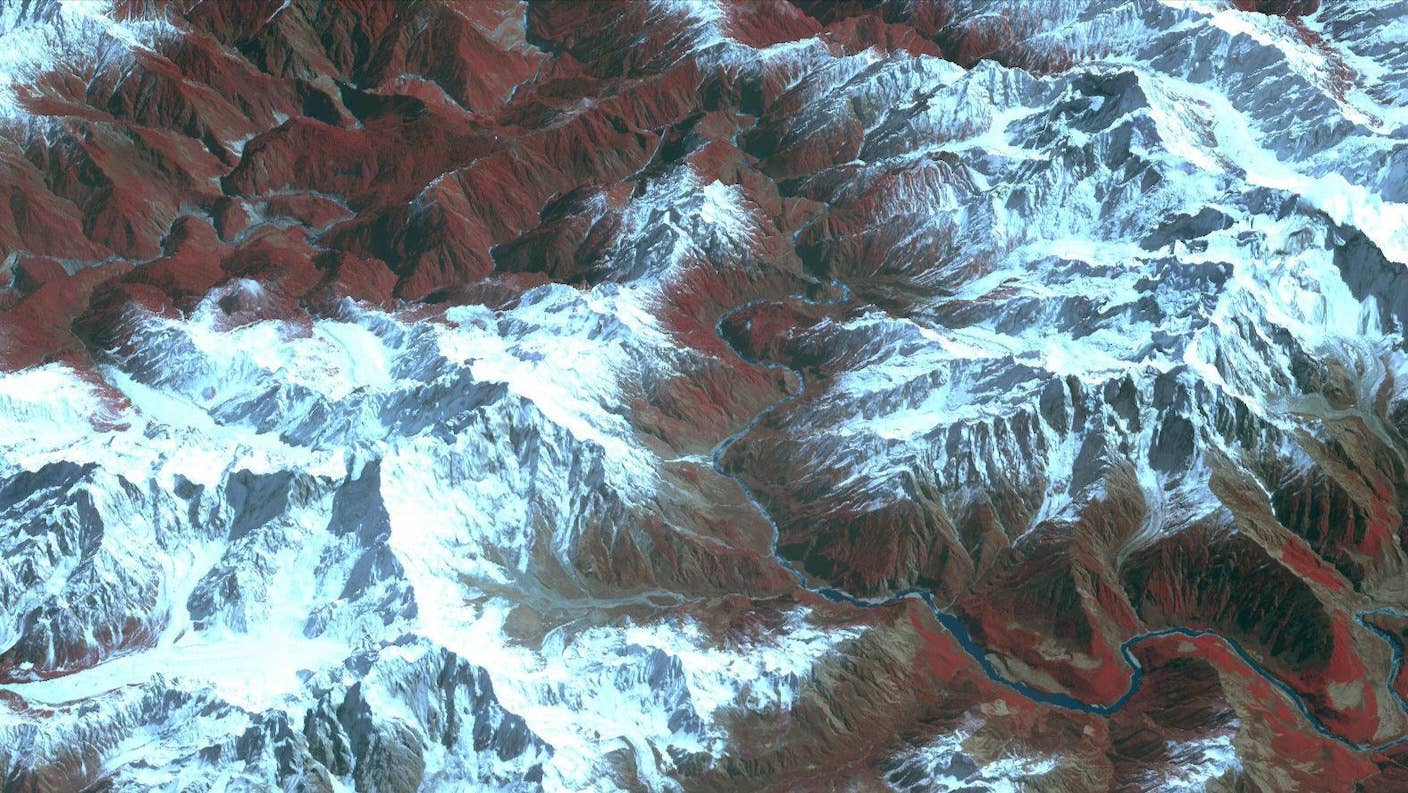

Image Credit

NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and US/Japan ASTER Science Team

Share

China’s electricity use over the last 30 years is a hockey-stick curve, climbing steeply as the country industrialized, built dozens of mega-cities, and became the world’s manufacturing center. Though China’s economy has slowed in recent years, electricity demand is only climbing. Given the country has pledged to reach carbon neutrality by 2060, they’re going to need much more renewable power than they currently have.

To help them achieve that goal, the government recently announced plans to build the biggest hydropower dam in the world.

Medog Hydropower Station, as it will be called, will blow other hydropower dams out of the water (pun intended), with an estimated annual generation capacity triple that of the world’s largest existing dam (which, perhaps unsurprisingly, is also in China). The 60-gigawatt project will be able to generate up to 300,000 gigawatt-hours (or 300 terawatt-hours) of electricity per year. That’s equivalent to Greece’s annual energy consumption.

The dam will be built on a river in Tibet called the Yarlung Tsangpo, with construction carried out by the government-owned Power Construction Corporation of China. It will not only be one of China's biggest infrastructure projects ever, it will be one of the most expensive infrastructure projects ever, with an estimated cost of a trillion yuan or $136 billion (yes, billion with a “b”).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, China is already home to the world’s largest existing hydropower dam: Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River stands 594 feet tall (Arizona’s Hoover Dam is taller, but Three Gorges is wider) and has a generating capacity of 22.5 gigawatts. By comparison, the biggest hydropower dam in the US is the Grand Coulee in Washington state, and it has a generating capacity of 6.8 gigawatts. China is the world leader in hydropower deployment, accounting for almost a third of global hydropower capacity. Many of those dams are on the Yangtze (some of them built by robots!) and some are on the same river where the Medog project will be built.

The Yarlung Tsangpo river starts in western Tibet, flowing east and then south, where it merges with India’s Brahmaputra then flows south through Bangladesh and into the Bay of Bengal. It is the highest river in the world, and a 31-mile (50-kilometer) section in the South Tibet Valley drops by a sharp 6,561 feet (2,000 meters); there’s loads of untapped potential for all that moving water to turn some turbines on its way down.

But the project is not without its challenges, both engineering and political.

Environmental groups say the dam will disrupt ecosystems on the biodiverse Tibetan Plateau. Tibetan rights groups see the project as a prime example of China exploiting Tibet’s natural resources while harming local communities. The dam’s construction will require people to be relocated, though likely not as many as Three Gorges, which uprooted and moved 1.4 million people. The Medog dam will be bigger, but it’s in a more sparsely populated area.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

India and Bangladesh have both expressed concerns about the dam, as it could alter the flow of the river downstream where it runs through these countries. There are also concerns about the area’s geological stability, as it sits at the convergence of the Indian and Eurasian continental plates and is considered tectonically active. An earthquake could destroy the dam and cause catastrophic flooding. In fact, a magnitude 6.8 earthquake killed 126 people and damaged 4 reservoirs just last week.

However, Medog won’t be a conventional dam in the form of one giant wall built to hold water behind it, like Three Gorges or the Hoover Dam. Instead, four 12.4-mile (20-kilometer) tunnels will be blasted and excavated through a mountain called Namcha Barwa to divert the river. The water flowing through these tunnels will turn turbines attached to generators before running back into the Yarlung Tsangpo.

The Chinese government says the Medog project will help it achieve the country’s carbon neutrality goals. In 2023, coal was still China’s main source of electricity generation by a long shot, supplying 61 percent of the country's electricity. Hydropower was a distant second at 13 percent, followed by wind, solar, nuclear, and gas, in that order.

Construction is slated to start in 2029, and if all goes as planned—which would be impressive for a project of this scale—it will take four years to complete, with the dam beginning commercial operation in 2033.

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

Meta Will Buy Startup’s Nuclear Fuel in Unusual Deal to Power AI Data Centers

Your ChatGPT Habit Could Depend on Nuclear Power

Hugging Face Says AI Models With Reasoning Use 30x More Energy on Average

What we’re reading