Most of us live in two separate worlds, the real world and the digital world of the Internet. Some strides are being made, like controlling your car with your smartphone, but there are surprisingly few ways to bridge the worlds together. Ninja Blocks aims to change that. Think of a Ninja Block as a Raspberry Pi computer that interfaces with objects and senses environments. Each Ninja Block is a powerful mini computer with a built-in accelerometer and thermometer complete with multiple USB ports and an ethernet port to connect the physical world to a host of web services.

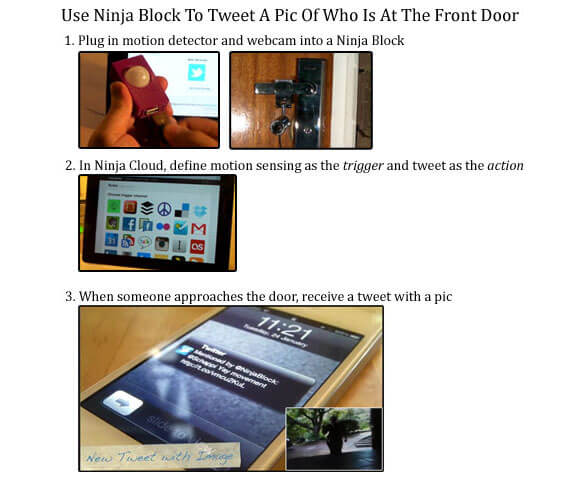

For example, say you wanted to be notified if the postman or UPS comes near the front door. You could use a Ninja Block to not only sense it, but tweet you a picture and send a copy to DropBox. Another situation when it could be handy is alerting you that one of your friends just logged into Xbox live by switching on a lamp in your living room. Or if you have a dog that can’t stay off your bed during the day, a Ninja Block could help you train it by playing a sound or a voice recording every time it tries.

Each block is its own little computer, so it can respond to stimuli, process inputs and outputs, and interface with the cloud just by plugging stuff in and defining a rule. Because setup is fairly straightforward, a Ninja Block can be easily switched from one use to the other.

Marcus Schappi, co-founder and president of Ninja Blocks, describes what is at the heart of these devices:

We designed our own Arduino-compatible board that fits as a daughter shield on the Linux-based BeagleBone. It’s like connecting an Arduino to a little computer running Ubuntu. We’re getting the best of both worlds here: a board that can use the tried and tested Arduino code for sensors and actuators, and the power of a tiny Linux computer that can do things like video and audio processing.

We designed our own Arduino-compatible board that fits as a daughter shield on the Linux-based BeagleBone. It’s like connecting an Arduino to a little computer running Ubuntu. We’re getting the best of both worlds here: a board that can use the tried and tested Arduino code for sensors and actuators, and the power of a tiny Linux computer that can do things like video and audio processing.

Arduino boards continue to pop up in a bunch of new gadgets, such as clothes, drones, and DIY biology labs, and we recently covered the Descriptive Camera, which uses BeagleBone. So it’s exciting to see how these devices and their derivatives are finding versatile uses. In fact, the site has received requests for the custom-designed daughter board, which will be available sometime in the future.

Marcus has been busy with open source electronics since he graduated from the University of Sydney and started the Little Bird Company in 2006 specializing in online electronics distribution. But to get Ninja Blocks off the ground, he and the other co-founders appealed to the Kickstarter community with a pitch that showcases what the blocks can do:

The Kickstarter campaign ended in mid-March acquiring 500+ backers and pulling in just over $100,000, four times the amount the team was seeking. Ninja Blocks bears some similarity to Twine, the gadget that pulled in nearly 4,000 backers and over half a million during its Kickstarter run. Because of the huge response they received, the folks at Supermechanical have been busy working through the issues in scaling up production. Fortunately, the smaller response to Ninja Blocks allowed them to keep production manageable with the first batch of Ninja Blocks already shipped and the second batch going out this month.

As the video shows,  Ninja Blocks connect to the web via Ninja Cloud, which is an interface showing a set of straightforward tasks set up as conditional “if this, then that” statements that connects to web apps. Interestingly, these conditional statements are the same task-system that’s behind IFTTT.com, a site that manages a host of web services and received $1.5 million in seed funding last January. So both are basically rules engines. Linden Tibbets, founder of IFTTT.com, said that people like the task-defining service because it gets them thinking, “I have this control over something that kind of controlled me up until now.” Because of the similarity between the two, IFTTT and Ninja Blocks are looking at ways to work together, according to Marcus.

Ninja Blocks connect to the web via Ninja Cloud, which is an interface showing a set of straightforward tasks set up as conditional “if this, then that” statements that connects to web apps. Interestingly, these conditional statements are the same task-system that’s behind IFTTT.com, a site that manages a host of web services and received $1.5 million in seed funding last January. So both are basically rules engines. Linden Tibbets, founder of IFTTT.com, said that people like the task-defining service because it gets them thinking, “I have this control over something that kind of controlled me up until now.” Because of the similarity between the two, IFTTT and Ninja Blocks are looking at ways to work together, according to Marcus.

Finally, the team is fully committed to the open source community, so like Bug Labs, the software and hardware (even the case) for Ninja Blocks is open source, so you can find it all on Github.

Now the cost is approximately $160 per unit and $260 for the full sensor package, but Marcus makes it clear that they chose to optimize the product rather than the price by actively integrating 3rd party devices into Ninja Cloud, so that the value of the Ninja Block will only increase. What does that mean? Ninja Blocks is designed so that it can work with any USB device and independently process audio and video. Down the road, the blocks could even integrate with Twine sensors as well as Kinect motion detection and Siri voice activations.

Clearly, Ninja Blocks are a first step in using the electronics that are currently available to build a physical-virtual bridge that anyone can use, not just DIY enthusiasts. While Raspberry Pi received a huge amount of buzz from the educational community, Ninja Blocks have been more or less under the radar, presumably because most people can’t imagine what they they might do with them. At the same time, people are becoming heavily reliant on their mobile devices, and if smartphones become the new TV remote, how long will it be before people start demanding to be able to tell their smartphones to turn on the lights, start the coffeemaker, and notify them when the shower is warm enough?

With it’s cool ninja logo engraved into the 3D printed cases, community-voted flashy color, and Festivus-like slogan, “The Internet Of Things for the rest of us”, the Australian-based Ninja Blocks just might be the kind of universal, easy-to-use little computers that can finally stitch our two worlds together.

[Media: AngelList, Ninja Blocks, YouTube]

[Sources: Kickstarter, Ninja Blocks, Technology Review, Wired]