The emergence of the avian flu in 2003 caused alarm around the world as it spread through countries in Asia, leaving victims in its wake. While largely contained to the bird population, for the relatively few humans unlucky enough to catch it the flu proved deadly. Now, two groups of perhaps seemingly mad scientists have successfully modified the H5N1 virus so that it could be passed easily between humans. One of them has already published the work for all the world to see, and the second is soon to follow. What kind of dangers will materialize in a world where the laboratory formulas for superflus and other potential bioweapons are out in the open?

Of the 603 people infected since the 2003 H5N1 outbreak, 356 have died – a 59 percent mortality rate (by comparison, the Great Flu Pandemic of 1918 that claimed the lives of over 50 million had a mortality rate of just 2 percent). Still, people could take solace in the fact that the flu, luckily, while very well suited to being passed between birds, was not effective at passing from human to human.

Until now.

Yoshihiro Kawaoka at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Ron Fouchier at Erasmus University in the Netherlands have both been able to modify the virus so that it now is easily transmitted between humans.

Understandably, some are none too happy.

The wisdom of making the DNA sequence of a potentially very deadly virus public was discussed extensively in the media and behind closed public health office doors in the months prior to publication. The University of Pittsburgh’s D. A. Henderson, who helped eradicate smallpox, issued an editorial last December in response to the “ominous news,” arguing that “the benefits of this work do not outweigh the risks.” That same month the World Health Organization expressed “deep concern” about the “possible risks and misuses associated with this research” and about “the potential negative consequences.” Also in December, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton provoked concerns further by being clear that we’re all talking about terrorists, citing “evidence in Afghanistan that…al Qaeda…made a call to arms for – and I quote – ‘brothers with degrees in microbiology or chemistry to develop a weapon of mass destruction.’”

The growing concern and condemnation seemed justified when the December tumult concluded with a ruling by the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB) that Kawaoka’s paper and Fouchier’s paper that was also in the works, be censored – that the mutations shouldn’t be published lest terrorist groups be given the secret formula for a superflu.

Now the debates raged within the scientific community, with one side rejecting the censoring of science in any form, the other side echoed D. A. Henderson’s doubt that the research was even merited in the first place. Long story short, the advisory board reversed their ruling in March after receiving ‘revised’ versions of Kawaoka and Fouchier’s papers. I use that term lightly, as all the mutation data is still there.

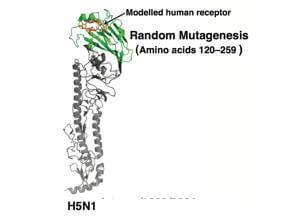

The key to Kawaoka’s (controversial yet FBI-approved) breakthrough was a viral protein called hemagglutinin that affects the ability of a virus to bind host cells. The hemagglutinin in H5N1 was well-suited to promote transmission of the virus between birds but not between humans. Kawaoka produced millions of H5N1 variants in which the hemagglutinin was mutated in different ways. When they screened the variants they found a version that, unlike its naturally-occurring counterpart, was very good at infecting human cells in a Petri dish.

The hemagglutinin of the human-targeting H5N1 virus showed four new mutations. Three of the mutations changed the shape of the protein from its normal shape and the fourth changed the pH level at which the virus attaches to cells and injects their genetic material. Sifting through the millions of mutations revealed a secret molecular formula for gaining deadly entry into human cells. To maximize the lethality of their creation, the team combined the mutated gene with the seven remaining genes – flu viruses have a total of eight genes – of a particularly transmittable flu virus; specifically, from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus.

And then they gave the modified viruses to ferrets. The new virus worked ‘beautifully,’ rapidly infecting ferrets separately housed in different cages. Assuming ferrets are a good model for viral transmission among other mammals, like humans, the scientists would have taken a virus that was relatively harmless to humans and turned it into a Franken-flu with a monstrous potential for harm were it ever to get out.

The paper, detailing what mutations went where, was published May 2nd in the journal Nature.

So should we be concerned about the world knowing that switching asparagine-224 to a lysine and a few other like changes turns a relatively harmless bird disease into a superbug threat for humans? A couple months ago during one of our Google+ Hangouts we brought up the debate to New York Times science columnist and writer of The Loom Carl Zimmer who’d last year wrote a book about viruses.

“I can sleep at night knowing that that’s going on but I don’t rule out the danger of it. On the other hand I do think there’s a danger in totally stifling this type of research. If somebody did release some sort of horrible bioweapon we would probably find a vaccine or cure if this information was available to people as easily and quickly as possible so that you’re essentially crowdsourcing a solution as opposed to, say, if anybody wants this data you’re going to have to fill out three thousand pages of paperwork and then we’ll get back to you, and in the meanwhile another thousand people have died.”

The practicalities of a quick and effective response aside, Zimmer isn’t too alarmed by the threat of a superbug let loose in the first place.

“I think an argument could be made that [a virus] is a pretty lousy bioweapon. There’s good chance that if you were…trying to make a very virulent kind of flu you might very well be the first person to die. But let’s imagine you were able to transport it to some other country and unleash it. Take a look at what happened in 2009 with the Swine Flu. It was first noticed in Mexico, and by the time scientists really had a good handle on it in Mexico, we now know that it was already all over the world, because people have been getting on planes and going all over the place. So, if some horrible person unleashed a very virulent flu in New York, a lot of people would get on planes and go back to that terrorist’s home country trying to escape the flu.”

Of course, anyone willing to unleash a virulent flu in New York might not have cared to think these matters through.

And the second recipe, Fouchier’s, which will be published shortly in Science, is rumored to formulate an H5N1 virus even more lethal than Kawaoka’s. Fouchier’s group took a slightly different strategy by jumpstarting it with mutations that fostered its transmission from birds to ferrets, but then instead of screening for mutations that made the virus transmissible between ferrets, they took viruses from sick ferrets and injected them into healthy ferrets. Mimicking the way the viruses adapt in nature the viruses mutated as they were artificially transmitted from ferret to ferret, until they began transmitting on their own. As Fouchier told the New Scientist, his flu “is transmitted as efficiently as seasonal flu.” With a near 60 percent mortality, let’s hope his observation is never confirmed. The seasonal flu already leaves between 250,000 and 500,000 around the world dead each year.

But the method by which Fouchier’s bird flu was created could be considered an argument for creating superflus in the lab in the first place. Injecting viruses from sick ferrets into healthy ones until they adapted simulates the worst case scenario for humans. Conceivably, all it would take for the bird-to-human H5N1 to become a human-to-human H5N1 would be a finite number of transmissions between humans. As with the ferrets, the virus would adapt. How many direct contact transmissions would it need before it became airborne? The virus passed between Fouchier’s ferrets need just ten transmissions.

Ten transmissions and five mutations – one more than Kawaoka’s virus needed. Either way, it’s a very short jaunt along evolution’s path to go from a relatively benign bird flu to the potentially most destructive infectious agent ever to face humanity. So if similar mutations are needed to make the virus airborne between humans, knowing ahead of time what those mutations are, as Zimmer pointed out, gives us a head start in creating a vaccine.

A good enough reason? You tell me. But in the end it doesn’t really matter which side of the issue you’re on because the superflu recipe is already out there. We know it’s the first of two, and we can bet that other publications will follow that are potential bioweapon cheat sheets for “horrible persons.” Surely the debate will rage on as these papers come out, with one side saying benefits don’t outweigh risk, the other side saying we can’t afford to not be prepared.

[image credits: Wall Street Journal, International Business Times, and Nature]

images: China, China2, Paper