We Need a Manhattan Project for Cyber Security

Share

Of the 6,494 words President Obama uttered in his January 2015 State of the Union address, only 108 of them were dedicated to the topic of our growing technological insecurity. Sure the leader of the free world has a lot on his plate, but the president’s legislative proposal to “enhance information sharing” and “mandate national data breach reporting” are likely to have a minuscule impact against a serious and growing problem.

Indeed suggesting these measly offerings would make any meaningful difference in our global cyber security is akin to applying sunscreen and claiming it protects us from a nuclear meltdown — wholly inadequate to the scale and severity of the problem. It is time for a stone-cold somber rethinking of our current state of affairs. It’s time for a Manhattan Project for cyber security.

The major hacking incidents over the past few months, whether it was the Sony Pictures attack allegedly carried out by North Korea or the hundreds of millions of accounts penetrated at Target, Home Depot, and JP Morgan Chase purportedly by Russian organized crime make it clear that all our online data — whether financial, personal or intellectual — is at risk.

But we have a bigger problem. Computers run the world. They run our airports, our airplanes, our cars, our hospitals, our stock markets, and our power grids, and these computers too are shockingly vulnerable to attack. Though we’re racing forward at break neck speed to connect all the objects in our physical world — the tools we need to run our society — to the Internet, we still fundamentally do not have the trustworthy computing required to make it so.

We’ve wired the world, but failed to secure it.

Indeed, it has become plainly clear that we can no longer neglect the security, public policy, legal, ethical, and social implications of the rapidly emerging technological tools we are developing. We are morally responsible for our inventions and though our technological advances are proceeding at an exponential pace, our institutions of governance remain decidedly linear. There is a fundamental mismatch between the world we are building and our ability to protect it. Though we have yet to suffer the sort of game-changing calamitous cyber attack of which many have warned, why wait until then to prepare?

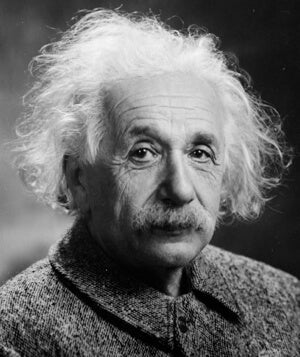

There are good examples in history where we as a society have brought together expertise in anticipation of catastrophic risk before it occurred. When it was discovered in 1939 that German physicists had learned to split the uranium atom, fears quickly spread throughout the American scientific community that the Nazis would soon have the ability to create a bomb capable of unimaginable destruction. Albert Einstein and Enrico Fermi agreed that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had to be apprised of the situation.

Shortly thereafter, the Manhattan Project was launched, an epic secret effort of the Allies during World War II to build a nuclear weapon. Facilities were set up in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Robert Oppenheimer was appointed to oversee the project. From 1942 to 1946, the Manhattan Project clandestinely employed over 120,000 Americans toiling around the clock and across the country at a cost of $2 billion. Those working on the Manhattan Project were dead serious about the threat before them. We are not.

While no sane person would equate the risks from the catastrophic impact of nuclear war with those involving 100 million stolen credit cards, we must surely recognize that the underpinnings of our modern technological society, embodied in our global critical information infrastructures, are weak and subject to come tumbling down either through their aging and decaying architectures, overwhelming system complexities or via direct attack by malicious actors. It’s high-time for a Manhattan Project for Cyber Security.

I’m not the first to suggest such an undertaking; many others have done so before, most notably in the wake of the September 11 attacks. At the time, a coalition of preeminent scientists wrote President George W. Bush a letter in which they warned, “The critical infrastructure of the United States, including electrical power, finance, telecommunications, health care, transportation, water, defense and the Internet, is highly vulnerable to cyber attack. Fast and resolute mitigating action is needed to avoid national disaster.”

Signatories to the letter included those from academia, think tanks, technology companies, and government agencies. These serious thinkers, not prone to hyperbole or exaggeration, warned that the grave risk of cyber attack was a real and present danger and called for the president to act immediately in creating a cyber-defense project modeled on the Manhattan Project. That call to action was in 2002.

Sadly, precious little has changed since then with regard to the state of the world’s cyber insecurity; if anything, the situation has grown worse. Sure, there have been nominal efforts but precious little substantive progress. What is America’s overarching strategy to protect ourselves from the rapidly emerging technological threats we face? We simply do not have one — a serious problem we may live to regret.

A real Manhattan Project for cyber security would draw together some of the greatest minds of our time, from government, academia, the private sector, and civil society. Serving as convener and funder, the government would bring together the best and brightest of computer scientists, entrepreneurs, hackers, big-data authorities, scientific researchers, venture capitalists, lawyers, public policy experts, law enforcement officers, and public health officials, as well as military and intelligence personnel. Their goal would be to create a true national cyber-defense capability, one that could detect and respond to threats against our national critical infrastructures in real time.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

This Manhattan Project would help generate the associated tools we need to protect ourselves, including more robust, secure, and privacy-enhanced operating systems. Through its research, it would also design and produce software and hardware that were self-healing and vastly more resistant to attack and resilient to failure than anything available today. Such a project of national and even global importance would have the vision, scope, resources, budgetary support, and perhaps most importantly, a real sense of urgency required in order to make it a success.

By bringing together those at the forefront of their respective fields, this Manhattan Project would also be able to forecast the troubling waters ahead. Though today’s technologies have been a boon for illicit actors, they will pale in comparison to the breadth and scope of technological change that will rapidly unfold before us in the coming years. Soon a plethora of exponential technologies now just in their infancy, such as robotics, artificial intelligence, 3-D manufacturing, and synthetic biology, will be upon us, and with them will come concomitantly profound, perhaps even life-altering, opportunities for good, but also for harm. In this exponentially accelerating world the ability of a single person to affect many — for good or evil — is now scaling exponentially, with implications for our common security.

Despite this, we plod forward, adopting newer, brighter technologies, each promising to solve a new problem or deliver a particular convenience. The problem is not that technology is bad; in fact, science and technology hold the promise of profound benefit to humanity. The problem, as we have seen, is that those with technological know-how, be they criminals, terrorists, or rogue governments, can use their knowledge to exploit an exponentially growing portion of the general public to its detriment.

Last night President Obama acknowledged “no foreign nation, no hacker, should be able to shut down our networks, steal our trade secrets or invade the privacy of American families.” But encouraging Congress to pass legislation on identity theft and data breach notifications is not nearly enough. There is a gathering storm before us. The technological bedrock on which we are building the future of humanity is deeply unstable and like a house of cards can come crashing down at any moment. It’s time to build greater resiliency into our global information grid in order to avoid a colossal system crash. If we are to survive the progress offered by our technologies and enjoy their abundant bounty, we must first develop adaptive mechanisms of security that can match or exceed the exponential pace of the threats before us. There’s no time to lose.

Adapted from the forthcoming book Future Crimes: Everything Is Connected, Everyone Is Vulnerable and What We Can Do About It by Marc Goodman, available February 24. Order your copy today.

Marc Goodman has spent a career in law enforcement and technology. He has served as a street police officer, senior adviser to Interpol and futurist-in-residence with the FBI. As the founder of the Future Crimes Institute and the Chair for Policy, Law, and Ethics at Silicon Valley’s Singularity University, he continues to investigate the intriguing and often terrifying intersection of science and security, uncovering nascent threats and combating the darker sides of technology. Follow him on Twitter at @FutureCrimes.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_message style="square" message_box_color="grey" icon_fontawesome="fa fa-amazon"]We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.[/vc_message][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Marc Goodman is a global strategist, author and consultant focused on the disruptive impact of advancing technologies on security, business and international affairs. Over the past twenty years, he has built his expertise in next generation security threats such as cyber crime, cyber terrorism and information warfare working with organizations such as Interpol, the United Nations, NATO, the Los Angeles Police Department and the U.S. Government. Marc frequently advises industry leaders, security executives and global policy makers on transnational cyber risk and intelligence and on the impact of technology in our lives. Marc provides audiences a front seat view into the digital underground on emerging technology, geopolitical, and security trends that will drastically redefine the markets in which they operate. Founder of the Future Crimes Institute, Marc’s current areas of research spotlight the security implications of disruptive technologies: artificial intelligence, the social data revolution, synthetic biology, virtual worlds, robotics, ubiquitous computing and location-based services. As Singularity University’s Faculty Chair for Policy, Law & Ethics, Marc focuses on the consequences, implications and virtues of exponential technologies in our lives. Moreover, he serves as SU’s Global Security Advisor, examining the use of advanced science and technology to address humanity’s grand challenges. For more than a decade, Marc worked with INTERPOL, the International Criminal Police Organization, having chaired numerous INTERPOL expert groups on emerging security threats. In that capacity, Marc trained police and security forces throughout the Middle East, Africa, Europe, Latin America and Asia and has worked in 70 countries around the world. In addition, he advises NATO as a subject matter expert on Critical Cyber Infrastructure Protection and the UN Counterterrorism Task Force on terrorist use of the Internet. Marc began his career as a serving police officer and uses his experience in global security and technology to advise clients on the next generation security threats which have emerged in our rapidly changing world. Marc Goodman is the author of Future Crimes: Everything Is Connected, Everyone is Vulnerable and What We Can Do About It from Random House/Doubleday. Future Crimes is a New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today Best-Seller, was selected as Amazon Best Business Book of 2015 and has been named one of The Washington Post Top Ten Best Books of 2015. Marc has authored more than one dozen journal articles and ten book chapters on on a variety of emerging security threats, including cybercrime, bio-security and critical infrastructure protection. Goodman is also a frequent contributor to many publications, including: Harvard Business Review, The Atlantic, Forbes, The Economist, Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, Oxford University Press, Jane’s Intelligence Review, the American Bar Association, the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, the Institute of Electronic and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). He has been interviewed by the BBC, CNN, Fox News, NPR, NBC, PBS, The Washington Post, LA Times, Le Monde, Larry King, Tim Ferriss, and many others. A sought-after speaker, Marc Goodman TED talk A Vision of Crimes in the Future, has been viewed more than 1.2 million times and translated into 26 languages. Marc holds a Master of Public Administration from Harvard University and a Master of Science in the Management of Information Systems from the London School of Economics. In addition, he has serves as a Fellow at Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation and is a Distinguished Visiting Scholar at Stanford’s MediaX Laboratory.

Related Articles

Hackers Are Automating Cyberattacks With AI. Defenders Are Using It to Fight Back.

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

Thousands of Everyday Drone Pilots Are Making a Google Street View From Above

What we’re reading