Mice Born From Artificial Eggs a ‘Stunning Achievement’

Share

Last month, a team of British scientists successfully made healthy, fertile mice from pseudo-egg cells that resembled fertilized embryos. The story made waves: compared to normal egg cells, the pseudo-eggs were more similar to non-sex cells such as skin cells. The implications were tantalizing: one day, in the far future, we may be able to make “motherless” babies without the need for eggs.

Welcome to the future.

This week, a team from Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan successfully used skin cells to make fully functional mouse egg cells completely in a dish. When artificially inseminated and brought to term in surrogate mothers, the artificial eggs developed into healthy baby mice that lived normal lives, eventually giving birth to pups of their own. The study was published in the prestigious academic journal Nature.

“This is a very exciting study, to be able to make robust and functional mouse oocytes (egg cells) over and over again entirely in a dish,” wrote Dr. Jacob Hanna, a reproductive scientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Revohot, Israel, who was not involved in the study, in an email to Singularity Hub.

Being able to culture eggs in a dish is a holy grail in biology, explains Hanna. The system lets scientists dig into the biology of fertility, which may help us uncover crucial genes and molecular events that help eggs develop normally.

Although the method’s success rate was about 3.5%, experts in the field are calling the study a “stunning achievement” that could potentially “eradicate infertility” if it can be applied in humans. The ability to make artificial eggs from any cell in the body could allow women who lack viable eggs or male-male couples to have genetic children of their own. “Reproductive age” may become obsolete.

“People might have thought this was science fiction, but it does work,” says Dr. Azim Surani, a stem cell biologist at the Gurdon Institute in Cambridge, UK, who had previously teamed up with study lead author, Dr. Katsuhiko Hayashi.

Hayashi agrees. Looking ahead, many years down the line, there is a possibility that we can produce human eggs from stem cells, he said in an interview with Nature.

But ethical implications need to be resolved before the method can be widely adopted, Hayashi warns. For example, it would be quite possible to introduce genetic mutations into the artificial eggs in culture. These “germ-line” mutations are currently banned since they can be passed down generations. In other words, the prospect of designer babies has never been closer.

Cooking Up Eggs In a Dish

Hayashi is not a newcomer to making artificial egg cells. Back in 2012, his team made headlines by successfully transforming embryonic stem cells and iPSCs into immature eggs in a cell culture system. (iPSCs, or induced pluripotent stem cells, are reprogrammed mature cells that theoretically have the ability to develop into any kind of cell type and tissue.)

But the method was incomplete. The immature cells had to be transplanted back into the ovaries of female mice to complete the maturation process. In a dish, the lab-grown precursor eggs withered and died. Why this happened was unclear, but the team speculated that something in an egg’s normal environment contributed to its development.

The new work closes that last leg of the maturation gap. Starting with either embryonic stem cells or iPSCs generated from female skin cells, the team first coaxed the cells to become precursor egg cells by forcing them to express a handful of genes. Then they mixed the precursors with clusters of mature non-egg cells taken from mice ovaries, in essence reconstituting an entire ovary in a culture dish.

Starting with either embryonic stem cells or iPSCs generated from female skin cells, the team first coaxed the cells to become precursor egg cells by forcing them to express a handful of genes. Then they mixed the precursors with clusters of mature non-egg cells taken from mice ovaries, in essence reconstituting an entire ovary in a culture dish.

After three weeks of careful culturing, the precursor egg cells began expressing genes that resembled those of a more mature egg. The researchers then carefully added a cocktail of hormones and other drugs — voila, another two weeks, and the delicate immature eggs had fully grown into mature egg cells.

This suggests we can sidestep implantation by supplying immature egg cells with supporting cells from the ovary in culture, explains Hanna. This makes the method much more possible, and easier, to do in humans since it’s less invasive.

In all, the team made over 50 lab-grown ovaries that produced over three thousand egg cells. Only a third made it all the way to full maturation, as many others contained mutations that prohibited their development.

Over 400 genes were expressed differently between the lab-grown eggs and eggs that develop naturally inside the body, the authors noted. The artificial eggs also had higher rates of chromosome abnormalities — that is, their DNA was not packaged correctly in the right numbers.

Nevertheless, about 3% of fertilized artificial eggs did develop into normal mouse offspring. In the last step, the scientists took their stem cells or skin cells and redid the process all over again, thus recreating the full cycle of life of an egg completely in a dish.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Motherless babies

Hayashi carefully notes that for now, female mice remain part of the equation.

We need to take supporting cells from their ovaries for the culture system, and in this study, we used fetal tissue, he explained. If the system were to be directly moved into humans, we would have to use tissue from aborted fetal embryos to get those supporting cells. That’s still an ethical grey area.

The next step is to try to make those supporting cells also from stem cells. “If we could establish such a culture system, that would be very useful for a human system,” says Hayashi.

The team is cautiously optimistic. According to Hayashi, his team plans to repeat the process in non-human primates first, which could potentially take almost a decade. As of now, the system is far too rudimentary for human use.

“We cannot exclude a risk of having a baby with a serious disease,” he says.

However, if the team irons out current issues of the system and manages to recreate entire ovaries in lab from skin cells, we will have an extremely powerful tool for all kinds of fertility conundrums.

Women with genetic fertility issues or who are less fertile due to age or disease could bear children of their own using lab-grown egg cells carrying their DNA. Theoretically, the system could also allow gay couples to have genetic children developed from one partner’s skin cells, fertilized with another’s sperm.

That said, making eggs from male skin cells is a lot more difficult. In Hayashi’s experiments, eggs produced from the tails of male mice died during the first few rounds of cell division.

It’s likely this is because male cells carry a Y chromosome that needs to be removed, explains Hana. But this is already possible, he adds.

There’s no doubt that there are still many hurdles to overcome, and we’re far more willing to take risks in mice than when it comes to our own children — making the leap from a 3.5% success rate to a nearly perfect one will take time.

But the study is a game-changer.

“Sometimes when you know something is possible, it takes off the mental barriers you might have. You start being more optimistic,” says Surani. “I think it is possible.”

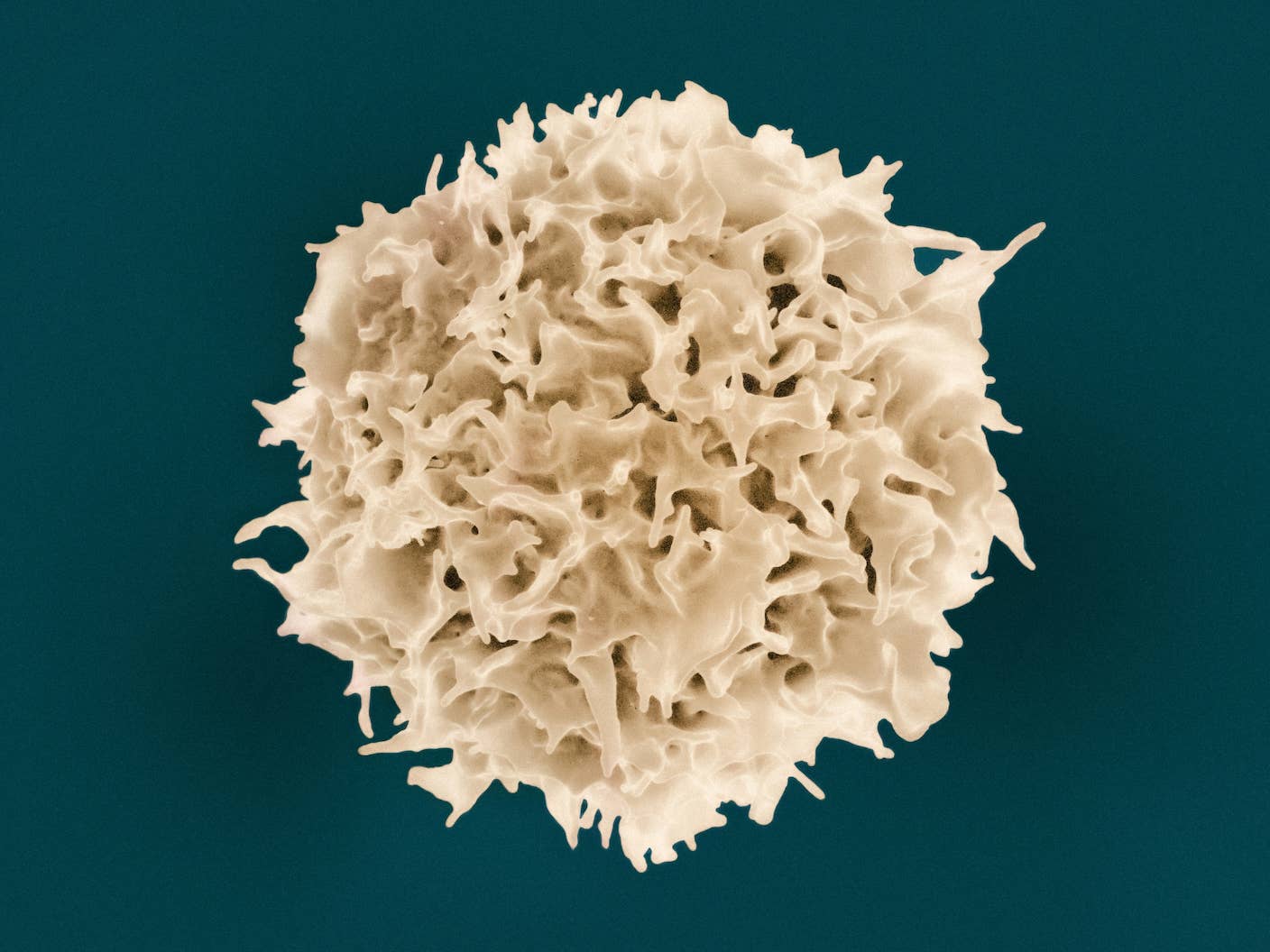

Image Credit: Shutterstock

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

AI-Designed Antibodies Are Racing Toward Clinical Trials

Sci-Fi Cloaking Technology Takes a Step Closer to Reality With Synthetic Skin Like an Octopus

Aging Weakens Immunity. An mRNA Shot Turned Back the Clock in Mice.

What we’re reading