Do we finally have a miracle weight loss drug? I mean, for real this time? The data seems to support such a claim, at least for overweight monkeys that simply can’t drop those extra pounds no matter what they try. After receiving the drug for just four weeks, the monkeys lost between 7 and 15 percent of the body weight, and averaged a more than 38 percent loss of total body fat.

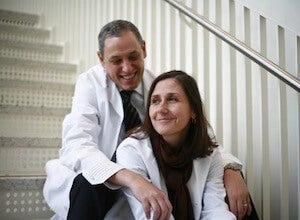

The study, published November 9th in the journal Science Translational Medicine, was headed by husband-and-wife team Wadih Arap and Renata Pasqualini at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Their drug, called Adipotide, targets the blood vessels that feed fat cells, or adipocytes. Attacking those blood vessels chokes off the nutrient supply that the fat cells need to survive and they either die or become stressed to the point that they don’t function.

Of course, blood vessels are needed to keep all cells alive. But the major medical advancement that adipotide brings is its ability to kill blood vessels associated with fat cells while leaving other blood vessels alone. The strategy has been long sought after by cancer biologists trying to kill cancer cells while leaving normal cells unharmed. Where others had failed, Arap and Pasqualini, cancer biologists themselves, succeeded by taking an approach that was novel in multiple ways.

A typical approach to drug development is to find or manufacture compounds that somehow slows or stops a disease. But instead of a targeted approach, the Arap and Pasqualini cast a wide net. Proteins in the body bind to other proteins, and which proteins get together is determined by their amino acid sequences. The Arap-Pasqualini team chopped up proteins into bits of peptide, or short chains of amino acids, injected them into the body and simply tracked where the peptides ended up. It’s as if the different parts of the body have different “zip codes” and each peptide sequence is drawn to a specific zip code. What made the study possible was the case of a brain-dead man who happen to be at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. The man had wanted his organs donated but his cancer had advanced too far. After explaining their experiment, the man’s family agreed to allow Arap and Pasqualini to inject their peptides into the man’s body. Afterwards, tissue from the man’s skin, muscle, bone marrow, fat, and prostate were collected to see if any peptides had specifically bound to one tissue and not the others. They found one that bound only to blood vessels in the prostrate.

In 2004 they conducted a study that bridges the gap between the cancer work and the current study. In the study they discovered a peptide that binds specifically to the blood vessels of fat tissue. Experimenting in obese mice, they showed that attaching a deadly substance to the peptide reversed the animals’ obesity, as they lost 30 percent of their body weight. In addition, metabolic impairments associated with obesity were also normalized.

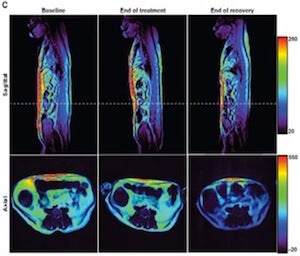

The current study is essentially the mouse study repeated in rhesus monkeys. Importantly, the monkeys were naturally obese – eating more an being less physically active than the other monkeys – and thus did not require any special interventions to make them overweight. After four weeks of treatment the monkeys experienced an average loss of 11 percent of their body weight. Physical measurements such as body mass index (BMI) and waistline – abdominal fat dropped 27 percent – were also reduced. Adipotide goes after the so-called white adipose tissue, or the unhealthy type that amasses beneath the skin and around the abdomen. The fat cells that die after having their blood supply cut off are reabsorbed by the body. Conversely, giving the drug to monkeys of normal size resulted in slight weight gain.

As with obese humans, obese monkeys displayed an increased resistance to insulin. After a meal insulin is produced by the pancreas and released into the bloodstream to promote sugar uptake by muscles. Thus, insulin resistance can lead to high level of blood sugar levels which, in turn, can lead to complications such as kidney failure, heart disease, and blindness. Insulin resistance is also a hallmark of type 2 diabetes, the devastating condition that, along with obesity, is fast on the rise in the US and the rest of the developed world. Adipotide showed additional promise as a diabetes drug, as it decreased insulin resistance in obese monkeys by 50 percent. Arap and Pasqualini discuss the study in the following video.

The demonstration in monkeys is a major step if Adipotide is ever to be realized as a treatment as many drugs have shown success in rodents but not primates. “All rodent models of obesity are faulty because their metabolism and central nervous system control of appetite and satiety are very different from primates, including humans,” Pasqualini explained in a press release.

So how soon could Adipotide benefit humans? The group is currently preparing for clinical trials that could begin as early as next year. They plan on giving the drug to obese patients that have advanced prostrate cancer. Mortality with prostrate cancer who are also obese is much higher than that with patients of normal weight. The patients will be given the drug for four weeks with the intent to battle both body weight and cancer simultaneously. The monkeys that took the drug displayed no indications that the drug made them feel sick, a reassuring sign that Adipotide might not have major side-effects. The monkeys did, however, show a modest degree of kidney failure. Side-effects will be a major concern during the human trials as treatment is expected to be given to the patients long term.

Another major question, of course, is whether or not the zip code strategy will be as effective in humans. If it’s less selective and attacks other blood vessels, side-effects could be dangerous. Obesity and cancer aside, the fact that it worked in monkeys is already scientifically interesting. It shows that not all blood vessels are the same, that blood vessels which supply blood to the, say, kidneys are different from those that supply blood to the prostrate. The finding opens up the possibility for site-specific drug delivery in other types of cancer and other diseases. Two companies are already working with Arap and Pasqualini to translate their drug targeting strategy to actual treatments. Ablaris Therapeutics is already working with the Food and Drug Administration to begin clinical trials testing Adiplotide’s potential as an obesity therapy. Alvos Therapeutics will do the same with a drug that targets prostrate-supplying blood vessels to treat prostrate cancer. A study on the drug has already been completed at M.D. Anderson but the results haven’t been reported yet.

In scientific circles, hypothesis-driven experiments are vaunted while “fishing expeditions,” such as throwing a drug at the body and seeing where it sticks, are often viewed as not ‘true’ science. But it’s hard to argue that Arap and Pasqualini’s blind, wide net approach to battling disease should be discouraged. I wonder what other “zip codes” these cancer-turned-obesity scientists discovered with their peptides. Certainly we haven’t seen the last of that data. For the sake of medicine, let’s hope that there were plenty more fish in the sea.

[image credits: Popfi, Chron.com]

image 1: Obese monkeys

image 2: Scientists

video: MD Anderson