New Surgical Technique Attempts to Re-grow Breasts After a Mastectomy (video)

Share

Researchers at the Bernard O’Brien Institute of Microsurgery in Melbourne, Australia are pioneering a radical new surgical procedure that would allow women to re-grow breasts after undergoing a mastectomy, a cancer treatment that removes part or all of a cancerous breast. After a decade of experiments in the laboratory as well as numerous tests on animal models, the researchers are ready to begin clinical trials to test the procedure in humans in the next few months. If all goes as planned, this treatment might become available within 3 years, providing an alternative to breast implants and reconstructive surgery for breast cancer patients. Further, if proven effective, this technology may have a wide range of applications in the clinic. Check out the video below for a CBS Healthwatch report on this exciting development!

A diagnosis of breast cancer is one that most women fear. And rightfully so. According to the National Cancer Institute, breast cancer in the United States “is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in women” (lung cancer is the leading cause by a wide margin). As is generally true for other types of cancer, early detection is crucial for survival. Starting treatment before the cancer has a chance to spread from its primary site results in a 5-year survival rate of 98%! And while being diagnosed with breast cancer is in itself devastating, the idea of losing one or both breasts is not exactly comforting either, though it’s not hard to imagine that most (if not all) women would rather lose their breasts than their lives. Some women with an extensive family history of breast cancer have even opted for a pre-emptive mastectomy, before ever being diagnosed. And options after a mastectomy include silicone breast implants or painful reconstructive surgery. However, the breakthrough being reported by the Australian scientists may change all of that.

https://cnettv.cnet.com/av/video/cbsnews/atlantis2/player-dest.swf

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

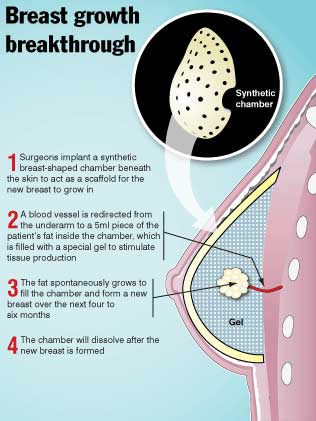

The new procedure, known as Neopec, is based on the use of a woman’s own stem cells to re-grow the breast. Doctors would first implant a biodegradable scaffold that is in the shape of a breast. Next, they would introduce fat stem cells into the area and nearby blood vessels would be redirected towards the implanted stem cells in order to supply necessary nutrients. Within 6 – 8 months, the cells are expected to grow and fill the area enclosed by the scaffold, which is then broken down by the body. The initial animal experiments used a non-biodegradable scaffold, requiring a second surgical procedure to remove it. Now, the procedure only requires the first surgery to implant the various components, making it less invasive and risky. Extensive testing in pigs has demonstrated the efficacy of this approach in allowing breast growth, though it remains to be seen if the clinical trials underway in humans will yield similar results.

Needless to say, this development is great news for the approximately 56% of cancer patients in the US who have the procedure done. However, our understanding of the mechanism of breast cancer development is becoming more refined and early detection continues to become more sensitive. Therefore, it’s not unreasonable to anticipate the development of more targeted therapeutics that may decrease the need for mastectomies altogether. So where else could this technology be applied? Initially, Neopec could be useful in cosmetic surgery. Women who desire to have larger breasts may be able to use this technique rather than having silicone implants, which already carry various risks to the patient. However, the real strength of this technology may be in applying it to regenerate other tissues and organs damaged by injury or disease. Here at Singularity Hub, we have already reported many promising attempts by scientists to engineer organs in the laboratory as well as using biodegradable implants to stimulate tissue regeneration. This latest innovation provides further evidence that we are only beginning to unlock the vast potential of stem cells as therapeutic agents. It’s exciting to imagine where this technology will be within the next few decades!

[image credit: perthnow.com.au]

[video credit: CBSNews]

[Sources: Bernard O'Brien Institute of Microsurgery, National Cancer Institute, Wikipedia, Herald Sun]

Related Articles

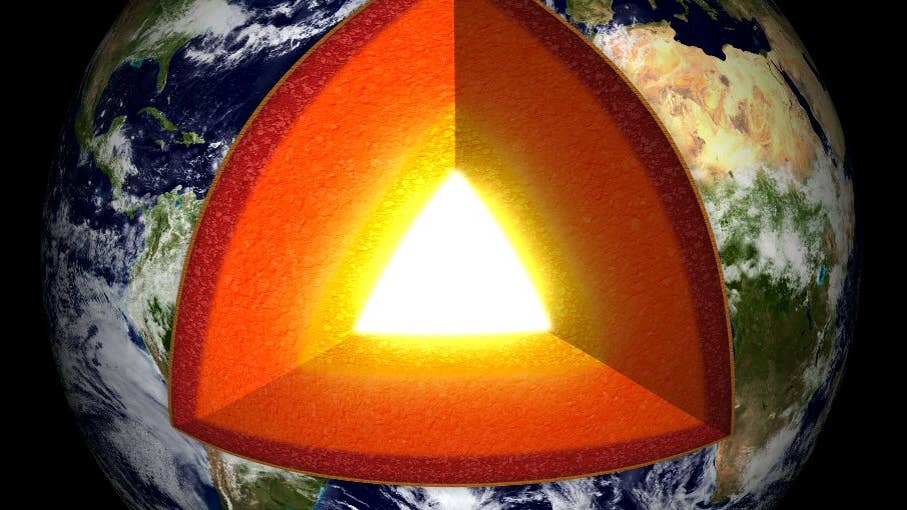

Vast ‘Blobs’ of Rock Have Stabilized Earth’s Magnetic Field for Hundreds of Millions of Years

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

Your Genes Determine How Long You’ll Live Far More Than Previously Thought

What we’re reading