Mark Roth Freezes Worms To Learn the Secrets of Preserving Life

Share

Every year people survive long periods underwater after falling in freezing lakes and rivers. Mark Roth and his colleagues at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center want to know why. A paper soon to be published in the journal of Molecular Biology of the Cell describes how Roth's team worked with yeast and roundworm cells to determine how they might hibernate in extreme cold. What they found seems counter-intuitive: if you want to survive in the cold you have to starve your cells for oxygen so they stop trying to live. Roth and his team have unlocked another key ingredient in understanding how we might produce suspended animation.

Roth has already reported some success in producing suspended animation in mammals using hydrogen sulfide to starve their cells for oxygen. As we mentioned in our discussion of that project, extremely low oxygen levels seem to be the key for inducing a protective and hibernating state. This recent work with yeast and roundworm embryos gives further insight into what allows cells to enter into suspended animation (more on that below). Ultimately, Roth's work will allow us to preserve humans after grave injury, putting them into chemical hibernation and maybe freezing them to give them the needed time to reach a hospital. This could save the life of many a soldier on a remote mission. One day, we may also find a technique that allows us to put humans 'on ice' almost indefinitely - giving us the means to store people with incurable illnesses, or to let astronauts wait in stasis during long space voyages.

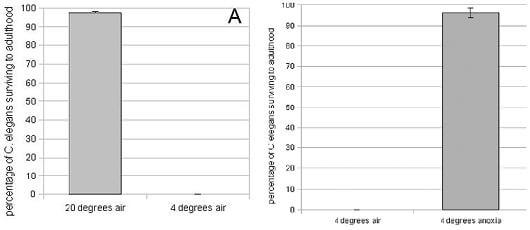

In their research, the team at the Hutchinson Center used two well studied organisms: S. cerevisiae (simple yeast) and the embryos of C. elegans (roundworm). After cooling both species (11-16C for yeast, 4C for worm embryos) for 24 hours, Roth found that more than 99% died (or were unable to live to adulthood in the case of the worms). That's pretty good indication that cold kills these organisms.

Then, the Roth team studied how an anoxic (zero-oxygen, pure nitrogen) environment affected each. After being starved for oxygen, both species were again subjected to low temperatures. After 24 hours, roughly two-thirds of yeast cells survived and reproduced while greater than 97% of roundworm embryos lived to adulthood. It's hard to get clearer evidence than that. Obviously anoxia helped save these cells from death from freezing.

You can see how low oxygen effects the life cycle of the micro-organisms in the following video from the Hutchinson Center. Watch for the effect of an anoxic environment around 1:00, and the revitalization of the worm embryo when oxygen returns at 2:00.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

So oxygen starvation can save a cell from a cold death. That's cool news, but something that Roth and others have known in one form or another for quite some time. The real discovery was this: anoxia saves cells from the cold by stopping the life cycles of the cell.

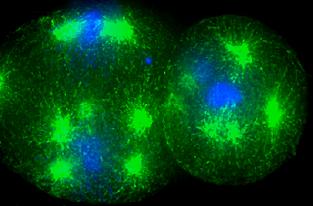

When a cell gets cold, some of the mechanisms for its reproduction get screwed up. In particular with C. elegans, the cell can't split and divide but it can still produce some of the microscopic structures (microtubule organizing centers or MTOCs) that reproduction requires. In essence, the cells build the infrastructure for a new cell but never makes the new cell. The results are like trying to build the Eiffel Tower inside your garage - things get crowded quickly. In the first 4 hours after being exposed to low temperatures, 43% of roundworm embryos were producing extraneous MTOCs. By 24 hours, more than 90% had done so. That sort of structural chaos leads to death once things warm up again. Oxygen starvation prevents the roundworm embryo from doing anything, including building MTOCs. When the cell warms up again, it simply resumes its normal routine.

Results with yeast showed very similar findings. According to the upcoming paper, "Anoxia-induced suspended animation prevents yeast cells from committing irrecoverable cell cycle errors at low temperatures." Again, cold temperatures disrupt the cell life cycle. Oxygen starvation stops the cell life cycle so that the disruption doesn't happen.

If all this sounds overly scientific...well, this is a technical paper, I suppose. But I can make it real simple: If you can somehow put a cell into a zero-oxygen environment, it has a good chance of going into suspended animation. The trick is how to completely rob cells of oxygen quickly. Roth's use of hydrogen sulfide is a good approach, but this experiment shows that it doesn't seem to matter how you get the cell to stop its life cycle as long as it does stop.

Which explains, in part, how people underwater can survive freezing temperatures for many minutes, even hours. Something must be robbing them of oxygen extremely quickly. Is it simply a chance side-effect of drowning? A chemical response to the freezing cold? That still needs to be determined, but Roth has shed a lot of light on what's happening at the cellular level...at least for microorganisms. As he continues with his work we'll get a better idea of how we can stop the life cycles of cells in more complex species, like humans. The work published here was actually performed in 2009 (alas the speed of scientific publishing is horrifically slow) so you can bet that Roth has already learned more as to the mystery of suspended animation. Give him more time and he may provide a way to preserve our bodies indefinitely. Those of us who are sick and dying may one day have a viable means for keeping ourselves alive until science can cure our conditions. Immortality here we come.

[image credits: WikiCommons (modified), Chan et al MBotC 2010]

[video credit: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center]

[source: Chan et al MBotC 2010, FHCRC News]

Related Articles

Sparks of Genius to Flashes of Idiocy: How to Solve AI’s ‘Jagged Intelligence’ Problem

US Solar Surged 35% in 2025, Overtaking Hydro for the First Time

More Space Junk Is Plummeting to Earth. Earthquake Sensors Can Track It by the Sonic Booms.

What we’re reading