With Mystery Solved, Promising Treatment for Parkinson’s Disease May Return

Share

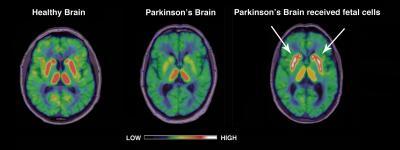

Researchers in the UK and Sweden may have solved the mystery as to why a revolutionary treatment for Parkinson's Disease had such disastrous side-effects. From the 1980s through the mid 90s, the big news in Parkinson's treatments was a cell transplant from the mid-brain of aborted fetuses into the brain of patients. Some patients enjoyed remarkable recoveries, with large reversals of symptoms and no further need of medication. Other patients showed little to no improvement. Many had an increase in dyskinesia (sudden uncontrolled movements). Now, the cause of that dyskinesia may have been tracked down. As reported in Science Translational Medicine, researchers found that patients with transplants had a higher than expected instance of serotonin cells, which in turn were affecting dopamine levels and inducing the dyskinesia. These scientists plan to resume Parkinson's fetal transplant research by 2012, giving rise to the hope that a new generation of the treatment might be perfected.

Efforts to treat and cure Parkinson's Disease have been boosted by recent donations to related research from such groups as the Michael J Fox Foundation (which partially funded the UK/Swedish work). Along with the study into fetal transplants, we've also seen multiple efforts to search for the genetic causes of the disease using SNP analysis. In fact, a report last year, also seen in Science Translational Medicine, demonstrated that gene therapy could have amble success in animal models. Yet transplant therapies are sometimes seen as more desirable because they would be possible in the near term. If the side-effects to such transplants could be avoided, we could possibly see them used as general treatments soon thereafter.

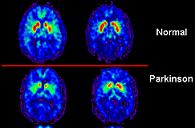

Marios Politis from Imperial College London spear headed the research to determine the causes of side affects to fetal-tissue transplants. He and his colleagues performed PET scans on the brains of patients who had received fetal cells 13 to 16 years ago and showed signs of dyskinesia. The scans showed increase serotonin activity in the brain. The ratio of serotonin neurons to dopamine neurons had increased dramatically. Politis and his team also studied how a serotonin inhibitor (5-HT1A or BuSpar) affected the uncontrolled movements. That medication greatly decreased the signs of dyskinesia, but only temporarily and without noticeable improvements in their scores on motor control tests. Still, the drug's effect is rather incredible to see. There are videos of the patients after treatment which can't be embedded here, but you can find them on the Science Translational Medicine website.

On the surface, the British-Swedish research seems very promising. It links a prohibitive side effect with a cause - excess serotonin neurons in the transplant. In the future, doctors could treat transplant cells to limit these neurons. It may even be possible to do this easily by reducing the storage times for these cells. Longer storage times are associated with subsequent increases in cases of pronounced dyskinesia. Politis is calling for more research into how storage times effect serotonin cell levels. The research also highlights the potential benefits of a serotonin agonist in treating dyskinesia.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Unfortunately there are severe limitations to this work. There were only 2 transplant patients used in this study. Two! 12 patients with parkinson's who didn't receive transplants, and 12 healthy individuals were also examined, but that was for control only. This small sample set casts major doubt on how important the serotonin link may be in causing dyskinesia. It's hard to fault Politis and his group, however, for this limitation, as many of the patients who received the fetal transplants had passed away in the following 15 years (many Parkinson's patients are over 65). Still, it's clear that further research is needed.

That research could be forthcoming. Politis has been quoted in Reuters and elsewhere as stating that UK and EU researchers plan on continuing transplant treatments in studies starting in 2012. They are likely to use the information garnered by the recent work by Politis to combat instances of dyskinesia in their patients.

In the long term, it's hard to know whether or not this treatment technique will gain widespread acceptance and use. Besides the ambiguity in whether or not serotonin levels are to blame for its major side effect, there's also the general moral/political controversy surrounding the use of fetal cells (aborted or otherwise) in research. If I had to make a guess it would be that pharmacological solutions (like the off-label use of BuSpar) are more likely to be the techniques generally adopted from this study. It's possible that stem cell transplants, especially adult pluripotent cells, may be able to skirt controversy and still benefit from the lessons learned by Politis and company. In the long term continued genetic research may eventually provide gene therapy solutions that make transplants obsolete. No matter how we pursue a cure for Parkinson's, however, it's clear that we'll be making every effort to tame this disease. The money is there ($175 million from the MJ Fox Foundation alone), the research will follow.

[image credit: WikiCommons, Politis et al, STM 2010]

[source: Reuters, Politis et al, STM 2010]

Related Articles

Sparks of Genius to Flashes of Idiocy: How to Solve AI’s ‘Jagged Intelligence’ Problem

Researchers Break Open AI’s Black Box—and Use What They Find Inside to Control It

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

What we’re reading