The Troubles With Modern Sleep: Myths, Memory, and Mortality

Share

Are you getting eight hours of uninterrupted sleep every night? ...Why? Though many of us consider the 8 hour (really, 7 to 9 hour) period of sleep as the ultimate way to rest, our bodies may be set up differently than we think. Natural sleep cycles tend to occur in several parts, change with the seasons, and take place partially in the day. Some people actively look to improve their sleeping habits by switching to several evenly spaced naps in a 24 hour period. Science may provide a way to get by on less sleep thanks to genetic engineering. Research at the UC San Francisco has identified a genetic mutation that allows humans, and genetically altered mice given the gene, to sleep less than their peers and still be awake and well rested. No matter how you look at it, our notions of when to sleep, how long to sleep, and why we sleep may need to be updated as we move into the future. Down a few caffeine pills, drink some warm milk, and crank up the volume on the white noise - it's time to re-examine our confusing and conflicting ideas about sleep.

Our first main problem is that people have largely strayed from 'natural sleep'. For the majority of living creatures on Earth, sleep is intimately connected to the Sun. Humans have tried to be an exception. The advent of widespread artificial light in the 19th century allowed us to start staying up later. In the 21st century the majority of people in industrialized countries have shifted their waking time so that it no longer directly corresponds to sunlight hours. That flexibility is what allows us to travel internationally, work in rotating shifts, and get things done. However, it could also be stunting our creativity, hurting our memory, maybe even sapping our intelligence. Here's Jessa Gamble, a science journalist in Canada, raising her concerns about our departure from natural sleep during her presentation at TED this year:

Gamble's talk is woefully short on scientific citations (her upcoming book on the subject is likely more thorough), but I can fill in some of the gaps. First, her assertion that people naturally sleep in two segments at night (known as segmented sleep) is well supported by a landmark paper by Thomas Wehr published in the Journal of Sleep Research. Back in 1992, while at the National Institute of Mental Health, Wehr demonstrated that people put into winter-like periods of sunlight (<10 hours) would develop a biphasic sleep. Essentially they slept, woke up, and slept again. During that intermediate waking period, the body produced larger amounts of the hormone prolactin (Gamble mentions this). Prolactin is reponsible for lactation in mammals, but it has also been linked to happiness, sexual gratification, and relaxation. What's so important about prolactin? Well it's one of the necessary hormones for our functioning, it counters dopamine, and it might help you stay smart. Research in the journal Science and the Journal of Neuroscience show that it helps increase mental plasticity in women during pregnancy. It may be doing the same in everyone.

'Natural sleep' is probably not eight hours of uninterrupted sleep. In fact, a little interruption is probably good, at least in longer winter nights. Humans in short summer nights (in Wehr's experiments) generally didn't experience biphasic sleep. But many people will tell you the importance of getting a nap during the day, especially during the hot summer. Research in Germany has shown that even a relatively short nap (20 mintues or so) can have a pronounced effect on memory. The siesta is good for you.

So, during some times of the year your body is probably adapted to sleeping longer each night with a break in the middle. And during all or part of the year your body probably wants a nap during the day. Returning to this 'natural sleep' cycle seemingly has mental benefits, and those that follow such cycles may be better able to remember important information, and stay alert.

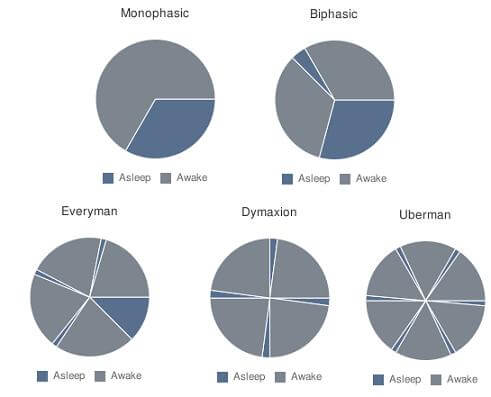

In an effort to capitalize on the segmented sleep phenomenon and to capture more awake hours during the day, some people have attempted to switch their clocks completely. They look to sleep a shorter amount of time per day (sometimes as little as two hours) and to do so in smaller chunks. This polyphasic approach to sleep has waxed and waned in popularity. YouTube and the internet at large are ripe with examples of people attempting, and generally failing, to switch to a new cycle. I don't really want to get embroiled in the controversy about whether such sleep cycles are feasible, so I'll pass the buck: here's a pro-polyphasic site, and here's one of the more popular counter arguments (with update). The following video features one of the more discussed researchers, Claudio Stampi, exploring polyphasic sleep in a semi-lab setting (make sure to watch till the end):

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Many of those wishing to switch to a polyphasic sleep schedule do so because they already have trouble with getting a good night's rest. Insomnia affects around 64 million people in the US, and many more around the world. While the causes of insomnia, and sleep deprivation in general, vary from case to case, the end results are almost universally unpleasant. Increased depression, lack of concentration, and feeling of stress are common complaints. Death may need to be added. A recent study published in the journal Sleep demonstrated that men who experience insomnia for more than a year had an increased incidence of mortality. In other words, although severe lack of sleep can't kill you directly, it lessens your chance for a long and healthy life.

I should point out, however, that some scientists feel that resting, not sleep itself is the necessary ingredient for survival. Researchers at the University of Wisonsin are exploring the possibility that falling asleep can be completely avoided. They point to numerous animals that challenge our ideas about the necessity of becoming unconscious.

Our modern world values productivity so much that people are willing to pursue longer waking hours, even though we generally know that a lack of sleep is both unpleasant and dangerous. In the future, we may all be able to stay awake without any of the dangers. Ying-Hui Fu and colleagues at UCSF have found that a mutation in the DEC2 gene can help some humans function better than their peers with less sleep. Transplanting that gene into mice allowed them to do the same. While the genotype for getting by on less sleep is certainly more complex than a single gene, Fu's work suggests that we may one day augment ourselves beyond the need for 8 hours of slumber.

That day is a long way off, and in the meantime I think we're going to continue to do silly, and probably even dangerous things, to avoid getting natural sleep based on sunlight patterns. We live in a world of 5 hour energy and late night television. We have grown accustomed to staying up to whatever time we want and sleeping as little or as much as we like. Most of us probably feel pressured to do more in each day, and our sleeping habits suffer.

When we examined longevity we discussed how a few simple lifestyle choices (eating healthy, getting regular exercise and avoiding stress) seemed to be the secret to living longer and healthier lives. For many of us, switching our diets and activities to mimic that example seems feasible. But what if we also need to go to sleep and rise with the sun? Could we do so? Would we even want to?

My guess is no. Even if natural biphasic sleep with a mid-day nap is probably the healthiest, I doubt many of us will pursue such a schedule. There's simply too much going on, too much pressure to work and play for us to sacrifice our flexibility. As our digital lives become more important we may face increasing pressure to stay connected for longer portions of the day, even though we know that unplugging is good for our health. The future may be filled with people striving to stay awake as much as possible. Genetics and other technologies could give us a means to do just that. Either way, it's pretty obvious we're going to try.

[image credits: Wikicommons]

[video credits: TED, Spinfuze]

[sources: Shingo et al Science 2003, Lahl et al JSR 2008, Wehr JSR 2008, Gregg et al JNS 2007, Vgontzas et al Sleep, 2010, He et al Science 2009, Cirelli et al PLOS 2008]

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 13)

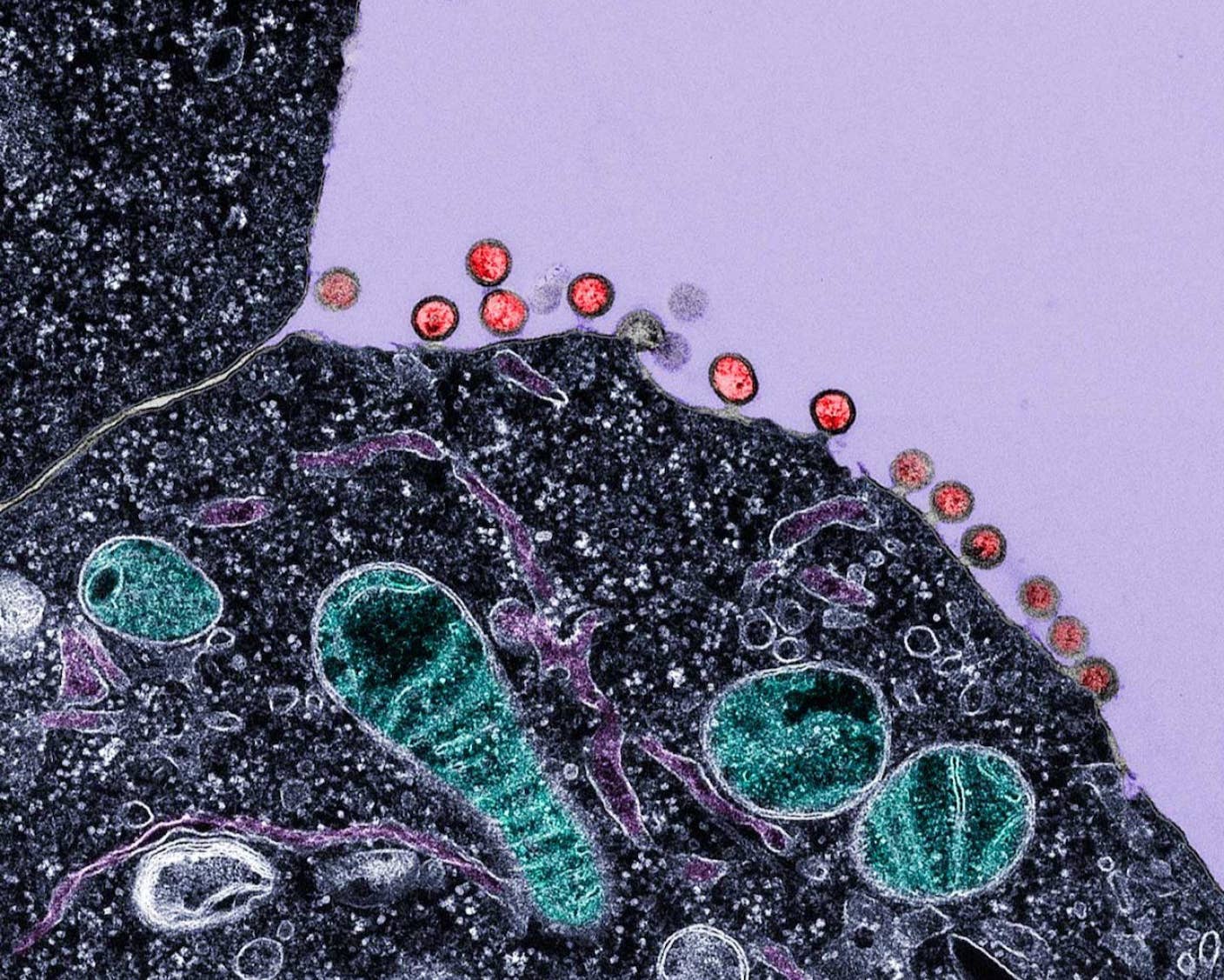

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

What we’re reading