First New Treatment for Lupus Erythematosus in Over Fifty Years!

Share

A small, but significant victory has been won in the war against lupus, one of the most debilitating systemic auto-immune diseases. The US FDA approved experimental drug Benlysta, the brainchild of Human Genome Sciences and the British GlaxoSmithKline Company, early last month. This will be the first new treatment for lupus in over fifty years. The disease is complicated, to say the least: its molecular mechanism still is not very well known, even though scientists have been trying to figure it out since 1948, with the disease itself having been first documented sometime in the 12th century. This makes the approval of Benlysta (generic name: belimumab) that much more important. The drug provides a greater variety of choices to affected individuals as the spectrum of symptom severity in lupus can be quite wide. However, before anybody gets their hopes up too much, it should be noted that the new treatment, while moderately effective, is far from being a cure.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), “the red wolf,” or just lupus, as it is commonly known, is an auto-immune disease that can affect multiple organ systems, but is most often expressed in the heart, joints, blood vessels, liver, and kidneys. The disease manifests in the organism producing antibodies against its own proteins (auto-immunity), especially those in the cells’ nuclei, which results in damaged tissues and inflammation. The range of symptoms is vast since multiple systems are affected, but most patients usually present with joint pain, anemia and a butterfly-shaped rash – a so-called trademark of SLE. Unfortunately, despite decades of modern scientific investigation, extremely little is known about the actual causes of SLE. It is presumed that SLE is triggered by several (unknown) environmental factors, although there is a strong indication for a genetic link. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region on chromosome 6 contains many genes that code for immune system proteins. Mutations of several genes in this region, collectively dubbed HLA Class I, Class II, and Class III, have been shown to confer increased risk of SLE. However, the environmental triggers are still thought to be necessary for the disease to develop, since lupus is not solely a genetic disorder.

One specific thing that is known about lupus on a molecular level is that affected patients cannot properly clean up the mess left behind after apoptosis, a process of programmed cell death, in which old cells are disintegrated and cleared away. Lupus patients have severe clearance deficiency of B-lymphocyte immune cells, the cells that are in charge of producing antibodies. Specifically, special cells called tingible body macrophages (TBMs), whose job is to digest B-cells that have undergone apoptosis are expressed in significantly lower amounts in patients with lupus erythematosus and other auto-immune diseases. This means that much debris and other apoptotic material left from the undigested B-cells is left free to float around the body. This unprocessed cellular waste, so to speak, is then targeted by the immune system as a foreign object and triggers a large-scale inflammatory reaction characteristic of auto-immune diseases such as SLE. The disease then manifests in the specific tissues in which this break-down in clearance of apoptotic material occurred.

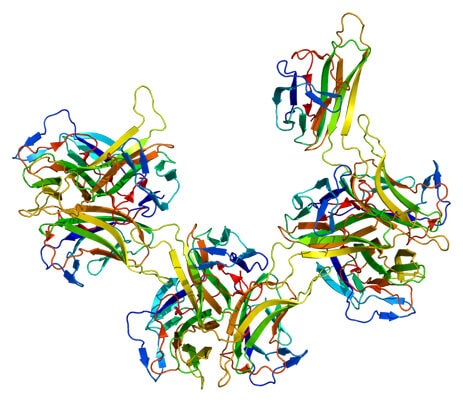

The new drug works directly to counter this mechanism. Belimumab acts against the TALL-1 protein, also known as B-Lymphocyte Stimulator (BLyS), which is involved in the proliferation of the antibody producing B-cells. By blocking the BLyS protein, belimumab curtails the spread of auto-antibodies that cause the inflammation in SLE. What makes belimumab special is that it is part of a relatively new class of drugs called fully human monoclonal antibodies. The idea of a monoclonal antibody, a so-called magic bullet that targets one specific antigen is not new, having been around since the beginning of the last century. However, belimumab is synthesized entirely from human proteins, helping to avoid many compatibility issues that arose in the past. Some may wonder why belimumab has been developed only recently, even though the TALL-1 protein was discovered back in 1999. The reason is that the antibody phage display technique used to produce fully human monoclonal antibodies was only perfected in 2002 by Cambridge Antibody Technology. As is often the case in modern science, discoveries or breakthroughs made by one group of scientists in one part of the world fuel the work of a different group located as far as across an entire ocean.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Belimumab has shown some promising results. In a recent Phase III study conducted by Drs. Doruk Erkan and Michael Lockshin of the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, and under the sponsorship of Human Genome Sciences and GlaxoSmithKline, 56.7% of lupus patients have shown improvement when treated with a 10 mg/kg dose of belimumab in addition to standard treatment as opposed to 43.6% improvement under standard treatment and placebo. This difference is significant enough to suggest belimumab as an alternative to the more rigorous corticosteroid treatments used for severe lupus cases today, which can cause serious side effects when used consistently over a long period of time. However, it should be made clear that belimumab is not viable for all lupus patients and is only intended for those with moderate-to-severe symptoms. Those affected with a milder version of lupus should be able to control their symptoms with other options such anti-malarial drugs, some of which are used as a treatment for SLE. Belimumab is also not appropriate for patients with nephritis, so that unfortunately means that those individuals in whom SLE has affected the kidneys may not be able to benefit from this new treatment. The nature of the drug itself is also far from ideal. As mentioned above, belimumab slows down the proliferation of B-lymphocytes, and while that does mitigate the symptoms of SLE, it should also be remembered that B-cells are involved in normal antibody production, which protects the body from infection. Therefore, while belimumab is a great alternative for patients who are not benefiting from traditional immunosuppressant drugs, its mechanism is still based on the idea of fighting against the immune system itself, which is, to put very simply, robbing Peter to pay Paul.

However, the approval of belimumab is an extremely significant milestone on the road to curing SLE and, possibly, other auto-immune diseases. Despite its imperfections, it is the first biological agent for lupus treatment in over fifty years to show substantial results and provide an alternative to existing therapies, some of which can be a bit too strenuous at times. It is our hope, here at Singularity Hub, that belimumab will serve not only as a fully-fledged lupus treatment in the present, but also as a possible springboard for even better auto-immune drugs in the future.

[Source: Hospital for Special Surgery, Journal of Leukocyte Biology, Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, Briefings in Functional Genomics and Proteomics, WebMD]

[Image Credit: Human Genome Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline Group, WikiMedia Commons]

I enjoy all types of futurology. I especially enjoy staying up to date with the latest advancements in machine learning and artificial intelligence. You can usually find me roaming the depths of the internet.

Related Articles

The US Plans to Break Ground on a Permanent Moon Base by 2030. Here’s What It Will Take.

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

Hackers Are Automating Cyberattacks With AI. Defenders Are Using It to Fight Back.

What we’re reading