A two-year old British girl born severely deaf due to a developmental disorder has spoken her first word after receiving a bionic ear.

The medical team led by Dr. Vittorio Colletti, the leading surgeon for installing ear implants in pediatric patients, performed the surgery on Evie Small last June in Verona, Italy. After recovering from swelling in her brain after the surgery, the device was turned on a month later.

In just two weeks, Evie heard her first sound and was able to clearly repeat her mother saying “mumma”.

More than simply enabling her to hear, the device is key to her cognitive development, ability to speak, and otherwise lead a healthy life in a world full of sound. That’s because the bionic ear isn’t a hearing aid — it’s an electronic auditory implant that plugs directly into her tiny brainstem.

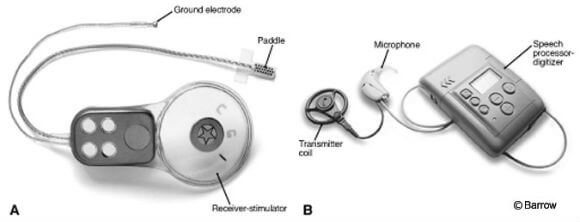

Though there are a variety of bionic ears on the market, an auditory brainstem implant is typically a two-component device. The first part is a speech processor that collects sounds using a microphone and coverts the analog data into digital radio signals. The second component, which is attached to a recess in the temporal bone of the skull, receives the radio signals and transmits them through an electrode paddle that is typically only a few millimeters long containing numerous electrodes.

The internal receiver-stimulator receives signals from the external radiotransmitter coil of the speech processor through the skin, and the coil is held in place either magnetically or, more recently, through a nonmagnetic plug and adhesive.

Although it seems that a bionic ear would be a smartphone-era innovation, the technology is actually three decades old. The first bionic ear surgery was performed in 1979 and consisted of a single channel intended to merely increase awareness of the environment and supplement lipreading. In 1991, the multichannel implant was developed and provided a richer set of frequencies for speech recognition.

During this time, cochlear implants were also developed that bypass damaged portions of the inner ear and have electrodes that attach directly to the auditory nerve. Today, a number of companies make implants, but the problem isn’t the technology as much as the wide range of success seen with the devices, depending on the degree of hearing impairment and the age of the patient.

Fortunately, for Evie and other young children with related severe auditory disorders and malformations, auditory brainstem implants have performed well, especially when performed early.

Evie was born with the rare oculo-auriculo-vertebral syndrome, and in her case, it meant that she lacked auditory nerves completely. This was only discovered when she was 16 months old, after wearing a hearing aid for a year without any signs of improvement.

She became a candidate to receive a bionic ear, but the window of time was short. Her doctors informed her parents that by two years old, the brain pathways for hearing would be developed to the extent that an auditory implant would likely have little benefit. Fortunately, the 40,000 euro (over $50,000) needed for the operation in Italy, where the implant surgery for children is permitted, was raised after her parents set up a foundation called Hope for Hearing.

You can watch Evie hear for the first time:

What’s amazing about this is that the sounds that Evie hears aren’t exactly like what we hear, but because her brain is still in development, it’s able to adapt. That means she can reproduce the sounds she is distinguishing clearly, which would be much less likely if she had received the device at a later stage. Still, she will need speech therapy to compensate for the early speech development she missed. Her parents also plan to use the foundation they’ve started to help other children with no hearing.

The 12-electrode implant that Evie received is manufactured by MED-EL, an Austrian-based company that recently announced the first successful implantation of an artificial vestibular device aimed at helping patients suffering from vestibular areflexia, which disrupts their sense of balance. Recently, a 24-electrode retinal implant was used to help a blind woman sees flashes of light and a woman who is paralyzed was able to mentally control a robotic arm to help her take a drink.

Wiring into the brain is bound to become more commonplace as the areas of cognitive science, artificial intelligence, cybernetics, and medical technology converge. Some devices, like the iBrain that monitors EEG signals to scan the brain, are becoming increasingly sophisticated, allowing brain interfacing without surgery. Technologies like auditory implants that have been around for years will likely see vast improvements, such as the waterproof cochlear implants that are being developed by Advanced Bionics.

For children like Evie, a bionic ear is a lesson in the transformative power of technology to change one life at a time.

[Media: bbc.co.uk, thebarrow.org]