Lab Grown Retinal Cells Implanted Into Blind Mice – And They Work

What if we could reverse degenerative forms of blindness with but an injection of new cells? Stem cell therapies—still promising, if not particularly speedy—may someday do just that. A recent paper in the journal Nature Biotechnology documents the successful implantation of photoreceptor cells, grown from embryonic stem cells, into the retinas of night-blind mice. The cells not only took root, but they remained present six weeks after implantation and formed the necessary neural connections to communicate visual data to the brain.

Share

What if we could reverse degenerative forms of blindness with but an injection of new cells? Stem cell therapies—still promising, if not particularly speedy in their development—may someday do just that. A recent paper in the journal Nature Biotechnology documents the successful implantation of photoreceptors, grown from embryonic stem cells, into the retinas of night-blind mice.

A team of researchers at UCL Institute of Ophthalmology and Moorfields Eye Hospital, led by Professor Robin Ali, obtained the photoreceptors from a “synthetic retina” grown in a lab dish using a new 3D cell culturing technique recently developed in Japan. The method more closely mimics the natural process of retinal growth in embryos, and allows researchers to better control the process of cell selection and extraction.

The researchers injected roughly 200,000 of the cultured cells into living mouse retinas where they not only took root but remained present six weeks after implantation and formed the necessary neural connections to communicate visual data to the brain.

Professor Ali and his team previously showed that injected photoreceptors from healthy mice can help blind mice see again, but the method, even if proven effective in humans, would suffer from a shortage of donor cells. The team's latest study shows lab-grown cell lines could provide a reliable supply for patients.

The technique has only been shown successful in mice so far, but Ali says, “The next step will be to refine this technique using human cells to enable us to start clinical trials.”

Clinical trials of neural stem cell implants like this are still years away, but trials of less complex stem cell therapies for the retina are already underway. Scientists at UCLA, for example, are conducting a clinical trial involving patients suffering from macular degeneration and Stargardt’s macular dystrophy—two common degenerative diseases causing blindness later in life.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The trials are founded on two cases where the researchers successfully implanted retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells derived from embryonic stem cells into the retina. RPE cells maximize light absorption in the retina and support the neurally connected photoreceptors with a variety of nutrients. In both macular degeneration and Stargardt’s, these cells die off, thus contributing to the broader degeneration of the retina.

The two patients, one suffering macular degeneration and the other Stargardt’s, reported moderate visual improvement after receiving the implantation of healthy new RPE cells. Dr. Steven Schwartz, the lead researcher for the UCLA trials, says stem cell therapies targeted at the RPE are the “low-hanging fruit” for stem cell therapies because they’re terminally differentiated, accessible, and form no synaptic connections.

Stem cell therapy isn't the only strategy in the war. While some researchers attack blindness by refreshing the biology—other want to use cutting edge machine implants. This pair of telescopic contact lenses, for example, or the Argus II optical implant (for those suffering from retinitis pigmentosa) aim to circumvent or augment the problem areas. The Argus II implant has been commercially available in Europe since 2011 (for a hefty $100,000) and was approved by the FDA here in the US earlier this year.

Even as researchers continue to make progress, scoring a major victory is an as yet distant goal. Ali told the Guardian, ""It certainly isn't a case of rolling out treatments in five years' time and providing therapies. It's taken us 10 years to get here and it'll take us five years to get started in people."

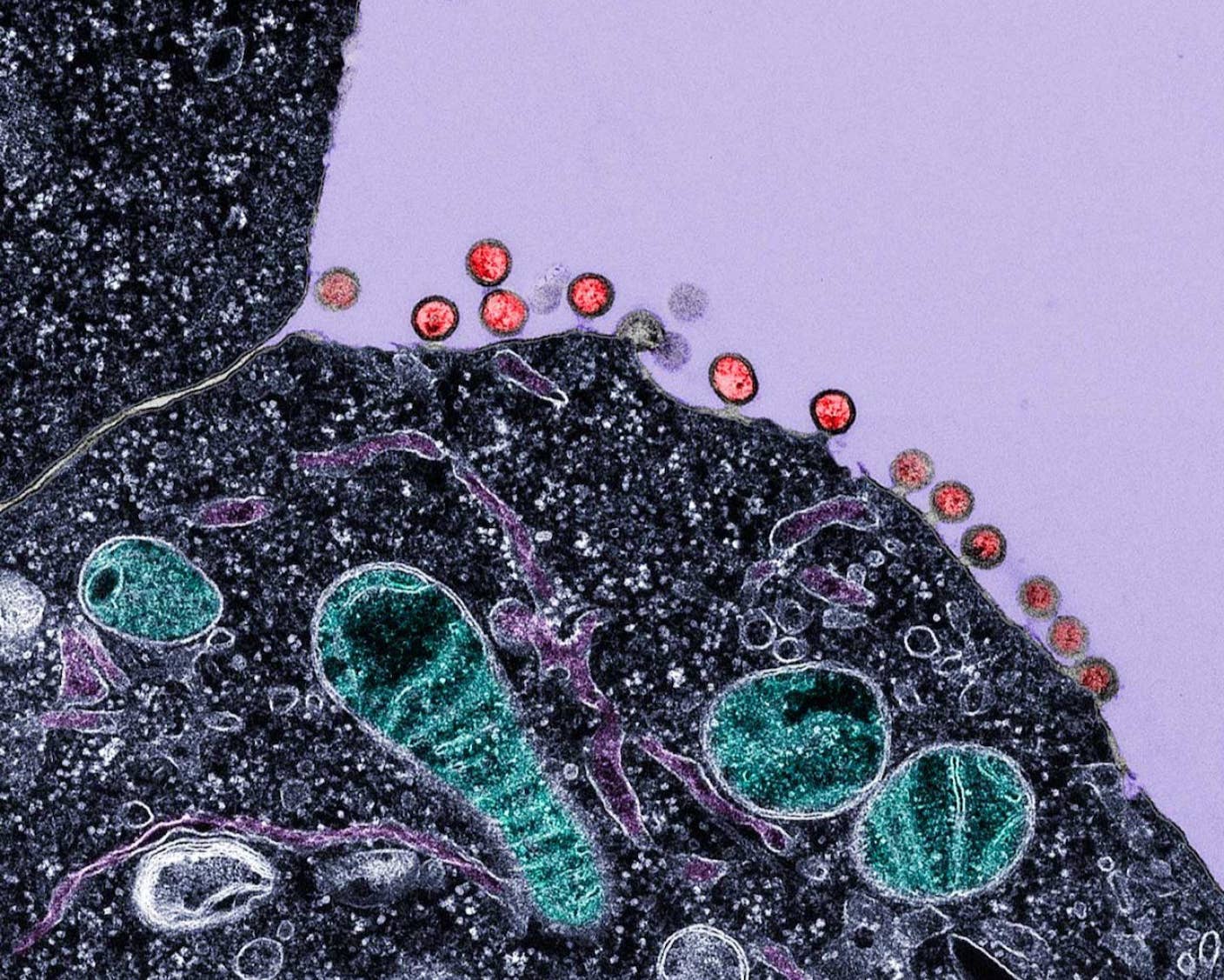

Image Credit: liesvanrompaey/Flickr (featured, banner), Umberto Salvagnin/Flickr (body)

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 13)

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

What we’re reading