As Americans use digital methods for more of their interpersonal communications, law enforcement agencies have seized the opportunity to scoop up more information for cheaper than they could before, hoping to ferret out criminal activity. But violent crime still takes place in the physical world, with fragile human bodies on the line. A growing number of U.S. police departments are using a system of sound-detecting software to locate and respond to gunfire in hopes of catching more shooters and saving more victims.

ShotSpotter, the dominant gunfire detection technology on the market, gathers data from a network of acoustic sensors placed at 30-foot elevation under a mile apart. To cut costs, most cities use the sensors only in selected areas. The system filters the data through an algorithm that isolates the sound of gunfire. If shots are fired anywhere in the coverage area, the software triangulates their location to within about 10 feet and reports the activity to the police dispatcher. The system is generally more accurate and more reliable than would-be 911 callers, in part because in the worst neighborhoods, residents don’t even bother to report gunshots.

Roughly 70 U.S. cities currently use ShotSpotter, which is made by the Newark, Calif., company SST. More police departments began subscribing to ShotSpotter after the company launched in 2011 a cloud-hosting platform that made the system more affordable for small and mid-size cities.

Roughly 70 U.S. cities currently use ShotSpotter, which is made by the Newark, Calif., company SST. More police departments began subscribing to ShotSpotter after the company launched in 2011 a cloud-hosting platform that made the system more affordable for small and mid-size cities.

Last month, SST began using the data its systems collect nationally to publish a quarterly index of gun activity in the United States. The index is based on data from a statistically representative set of about 120 square miles in just over 30 cities that use ShotSpotter. SST hopes the information will support the government’s rekindled interest — in the wake of the Newton, Conn., shootings — in research on gun violence. Of course, the index is also a clever marketing effort, emphasizing just how much the old human methods of reporting gun violence don’t tell us about gun use.

Currently, data on gun violence comes primarily from three main sources: 911 calls, mandatory reports hospitals file when they treat gunshot victims, and coroner reports on homicides or suicides involving guns. Such methods don’t document shots fired to scare people or kill animals. They also overlook, for example, gun battles in which bystanders don’t call police and victims seek to evade police attention by doctoring wounds themselves. All told, less than 20 percent of gunshots result in a 911 call, according to SST.

“Gun violence is significantly under reported — and misreported — at the very moment this critical epidemic needs precise and reliable data from a research perspective,” said SST CEO Ralph Clark.

SST’s data at least partially explains why more people don’t report gunfire to authorities. In the most active city in its index, an area covering a single square mile experienced 2,858 bullets fired in a three-month period. That’s 32 rounds fired every day. (The locations of the events included in the index are not identified.)

SST’s data at least partially explains why more people don’t report gunfire to authorities. In the most active city in its index, an area covering a single square mile experienced 2,858 bullets fired in a three-month period. That’s 32 rounds fired every day. (The locations of the events included in the index are not identified.)

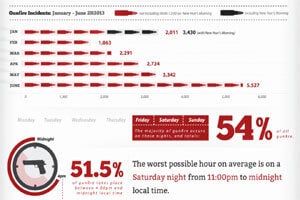

Another interesting nugget: Celebratory gunfire isn’t unique to foreign countries. In the United States, gunfire on New Year’s Day made up nearly half of all gunshots in January.

Sadly, gunfire increased in the United States in the second quarter of this year. The number of incidents recorded in the second quarter was nearly 50 percent higher than those in the first quarter. The trend included not just the most violent cities but also more moderate ones.

ShotSpotter adds to the nationwide trend toward data-driven policing, epitomized by the CompStat system introduced in New York City in the mid-1990s. Law enforcement officers see data as a way to help them allocate resources effectively.

“Today’s most effective policing strategies combine proven practices and tactics with new data and intelligence. When you consider the tragic consequences of gun violence, it’s critical that law enforcement professionals have all of the information available to more effectively deploy resources in high crime areas,” Boston Police Commissioner Edward F. Davis said in an SST press release.

But critics have pointed to problems with the technology and ShotSpotter has met with some resistance in many of the cities that now use it.

But critics have pointed to problems with the technology and ShotSpotter has met with some resistance in many of the cities that now use it.

Some are frustrated that, given the steep cost of the system, it doesn’t always successfully differentiate the sounds of guns firing from those of cars backfiring or firecrackers exploding. A San Francisco Police Department spokesman told Singularity Hub the system has trouble with fireworks, and a recent audit in Suffolk County, New York found similar problems.

Some also fear the police will use the technology selectively, spurring more arrests in some neighborhoods than in others.

“Part of the problem with law enforcement technology is that you want to put it in the place where there’s hot crime. So you’re listening in on some neighborhoods more than others, but you want to deploy resources where there’s the most crime. This is a question for police departments more generally that goes beyond just this technology,” Sarah Lawrence, the director of policy analysis at the Warren Institute at Berkeley law school, told Singularity Hub.

But because ShotSpotter’s sensors only pick up gunfire and the occasional firecracker, not conversation, the technology doesn’t seem to raise hackles as much as license plate scanners and video cameras do. Still, city residents will likely form more informed opinions of the technology as their local police departments get used to it, using it not just to dispatch officers more quickly to potential crime scenes, but also to identify and prosecute the perpetrators.

ShotSpotter has already been used as evidence in hundreds of criminal cases and has helped secure at least one murder conviction, according to SST.