Tiny Lab-Grown Heart Beats On Its Own

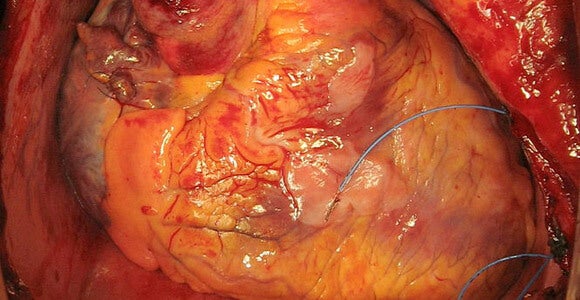

A growing number of researchers are looking to build hearts, like other organs, from biological tissue. Such hearts have the added benefit of using the patient’s own tissue, reducing the chance of rejection. Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh medical school made a significant breakthrough: They created a heart that beat on its own.

Share

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death worldwide, and doctors have struggled to find effective treatments. Heart failure, an especially dire form of illness in which the organ ceases to pump adequately, affects roughly 26 million people worldwide. Many don't respond to medication and are left waiting for transplants. But donor hearts are so scarce that just one percent of patients who need heart transplants get them.

A growing number of researchers are looking to alleviate the problem by building hearts, like other organs, from biological tissue. Such hearts have the added benefit of using the patient’s own tissue, reducing the chance of rejection.

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh medical school have made a significant breakthrough on this front, reported earlier this month in Nature Communications: They created a heart that beat on its own (video).

"Scientists have been looking to regenerative medicine and tissue engineering approaches to find new solutions for this important problem. The ability to replace a piece of tissue damaged by a heart attack, or perhaps an entire organ, could be very helpful for these patients," said Lei Yang, the lead researcher.

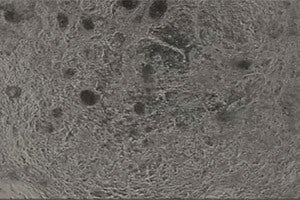

The researchers took a mouse heart from which everything had been removed but the basic structure and laid onto it cardiovascular cells developed from human induced stem cells. The human cells specialized into endothelial (or lining) cells, smooth muscle cells and muscle contractile cells. The resulting heart beat on its own and responded to medications.

Previous efforts to grow a heart in the laboratory had used pluripotent stem cells, but Yang’s experiment added an additional step. Researchers let the stem cells begin to develop for six days and then transferred just the cardiovascular progenitor cells to the heart scaffolding. That meant that none of the cells that grew on the scaffolding developed into liver cells, for example.

The greater stock of functional heart cells gave the heart enough power to beat. Using only cells that have already begun to specialize as cardiovascular cells also reduces the chances that tumors will develop in the bioengineered organ, Yang told Singularity Hub.

Still, the mouse-sized heart did not beat with the strength or synchronization that would be necessary to support a living organism. Researchers have yet to hit upon a way to grow cells as thick and densely packed in the laboratory as they are in the human body, a significant challenge facing regenerative medicine.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

“Other scientists are using this technology to regenerate the liver, the lung. The heart probably is going to be a difficult organ — those other organs, they’re not beating. We have a beating rate; the beating rate is controlled by the cardio-conduction system. It’s really hard to regenerate a whole conduction system,” Yang said.

The stem cells in the experiment were “induced,” or made, from adult connective tissue — a procedure that would make it possible to use a patient’s own tissue to build a heart. The patient’s immune system wouldn’t, therefore, identify the tissue as foreign and attack it.

However, the structural scaffolding for such bioartificial hearts can’t come from live patients. The next move for Yang and his colleagues will be to use as a scaffolding a stripped-down heart from a human cadaver available for research.

Still, given the magnitude of heart disease and the scarcity of donor hearts, many are hopefully eying the progress toward a bioartificial heart.

Images: A transplanted human heart, Vasily I. Kaleda via Wikimedia Commons; Lei Yang photo UPMC, regenerated heart photo UPMC

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Souped-Up CRISPR Gene Editor Replicates and Spreads Like a Virus

Your Genes Determine How Long You’ll Live Far More Than Previously Thought

Google DeepMind AI Decodes the Genome a Million ‘Letters’ at a Time

What we’re reading